We share Michael Roberts latest commentary on the South African Elections but it is worth recalling that the present state of affairs has a lot to do with Nelson Mandela's deal with South African and global capital.'' His encounters with the global elite at Davos, the home of the World Economic Forum, convinced him that compromises were needed to be made with the financiers. It was also the late night encounters with the captains of South African capitalism such as Harry Oppenheimer that reinforced his belief that there was no alternative but the capitalist road."

"In the words of Mandela in an interview with Anthony Lewsis:

''Private sector development remains the motive force of growth and

development. From On the Death of Mandela. by Brian Ashley

South Africa: the dashing of a dream

By Michael Roberts

South Africa has a general election tomorrow, 15 years since the end of apartheid and six years since the death of Nelson Mandela. In those 15 years, the aspirations and hopes of most black South Africans (90% of the 58m South Africans) and, for that matter, many white South Africans, have been disappointed. In those 15 years, the majority have not seen any startling improvement in their living standards, education, health and public services. Indeed, for many, particularly young blacks, things are even worse. Inequality of incomes, wealth and land is extreme; corruption in government and in the party of the black majority, the African National Congress (ANC), is rife.The death of Nelson Mandela in 2013 was a reminder of the great victory that the black masses of South Africa achieved over the vicious, cruel, and regressive apartheid system first encouraged by British imperialism and then adopted by a reactionary and racist white South African ruling class to preserve the privileges of a tiny minority. Mandela spent 27 years as a political prisoner, and the people he represented fought a long, hard battle to overthrow a grotesque regime that was backed for decades by the major imperialist powers, including the United States and Britain.

But the end of apartheid in the 1990s was also attributable to a change of attitude by the white ruling class in South Africa and the ruling classes of the major capitalist states. There was a hard-headed decision by them to no longer consider Mandela a terrorist and recognize that a black president was inevitable and even necessary.

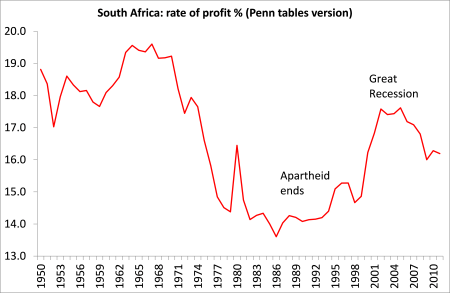

At the time, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, South Africa’s capitalist economy was on its knees. This was not just because of global boycotting of its exports but because the productivity of black labour in the mines and factories had dropped away. The quality of investment in industry and availability of investment from abroad had fallen sharply. This was expressed in the profitability of capital reaching a postwar low in the global recession of the early 1980s. Unlike other capitalist economies, apartheid South Africa could find no way of turning that around through the further exploitation of the black labour force.

The ruling class had to change strategy. The white leadership under F. W. de Klerk reversed decades of previous policy, opted to release Mandela and go for black majority government that could restore labor discipline and revive profitability. For his efforts, de Klerk shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Mandela, who was elected president at the age of seventy-six! And profitability did rise dramatically under the first Mandela administration as foreign investment poured in and the rate of exploitation of the workforce rocketed.

As one of the so-called BRICs, South Africa’s economy was traditionally rooted in the primary sectors – the result of a wealth of mineral resources and favourable agricultural conditions. Under Mandela and then later Thabo Mbeki, the black majority saw some improvements in their truly awful living situation, in sanitation, housing, electricity, education, health, and so on, ending the cruel and arbitrary control of movement and the inequality of the apartheid regime.

But despite its professed socialist ideology, written into its constitution, the ANC leaders quickly ditched any radical change to the economy and social structure. ANC governments opted for capitalism and never even considered any state takeover of the mines, resource industries and land owned by the whites. Instead the ANC leaders took a slice of the action themselves.

Thus the tiny, wealthy white minority has remained pretty much unaffected by the ending of apartheid. Now the rich whites have been joined by a few rich blacks who dominate the businesses and exert overwhelming influence over the ruling ANC. The party now expresses the sharp divisions between the majority of working-class blacks and the small black ruling class that has developed. These fissures erupt every so often, as yet without a decisive break.

By the early 2000s, the relative recovery of the economy began to peter out and then the Great Recession globally dealt a technical knock-out to South African capitalism from which it has not recovered. Profitability of capital dropped away and growth in investment, productivity and output began to crawl, making it impossible for the black majority to make any progress. South African industry is now in difficulty; unemployment and crime remain at global highs, and economic growth is foundering.

Investment stagnates (ZARm)

Gross domestic product grew by 2.9% on average between 1994 and 2000 under Mandela after apartheid wrecked the economy. And under Mr Mandela’s successors, growth accelerated to an average of 4.2% a year until the 2008 financial crisis. But the economy has stalled in the decade since, recording average growth of 1.6%.

Indeed, once population growth is taken into account, real GDP per person has been stagnating in the Long Depression of the last ten years.

Per capita GDP ($ per person)

The World Bank calls South Africa “the most unequal country in the world by any measure”. Inequality of consumption has increased under the ANC government to a huge gini ratio of 0.63. Inequality in wealth is even higher: the richest 10% of the population held around 71% of net wealth in 2015, while the bottom 60% held just 7%. Furthermore, intergenerational mobility is low, meaning inequalities are passed down from generation to generation with little change over time. Ramaphosa encapsulates the country’s failure to tackle inequality at its root. He is a wealthy tycoon, part of a narrow black business elite that has been forged by ANC policies.

The progress in poverty reduction in the early years of the ANC government in the late 1990s has also stopped. Even on the dubious World Bank figures of a poverty rate of $1.90 a day, 19% of South Africans are below this level compared with 17% in 2011. According to figures provided by Moeletsi Mbeki, brother of former president Thabo, only 37,000 black South Africans earn more than $4,300 a month. Those earning more than $820 number just 1.25m in a country of 58m people.

There are 8.3m people of working age with no job. Unemployment officially stands at 27.1% in the fourth quarter of 2018. The unemployment rate is even higher among youths, at around 54.7%.

Unemployment rate (%)

The racial and class divide remains in the extreme 15 years since apartheid was ended. The divide is entrenched early in people’s lives: in the education system. Almost all white pupils pass the final-year secondary school exams that are required to enter university. Only two-thirds of their black counterparts manage the same feat. Black South Africans also face disadvantages accessing healthcare and other services. Rolling electricity blackouts caused by long-running and ongoing problems resulting from mismanagement and corruption at the state utility Eskom plague the black communities.

Corruption in the higher echelons has increased. Transparency International’s index puts South Africa on 42 (where zero is total corruption) and that is down from 57 when apartheid ended.

Corruption index (lower means more corruption)

There is a national plan to take South Africa’s black millions out of poverty. The National Development Plan 2030 is official ANC policy but it has never been implemented. Moreover, the plan is really one of compromise with big business and landowners. The rich will pay more tax, the government will then provide better services (and be less corrupt), but real wages will be reduced so that employment can rise! This was the strategy of the ANC leaders under Ramaphosa offered in their election campaign.

But the ANC is in some electoral trouble. In August 2016 the ANC lost majority support in four of the metropolitan cities. Political parties negotiated coalition deals that saw the ANC unseated in the cities of Johannesburg, Pretoria and Nelson Mandela Bay. In this election, there is a possibility that, although the ANC will win again, it will poll less than 50% for the first time.

Ramaphosa says he wants to reduce corruption at the top but the ANC party apparatus is still controlled by the cronies of former President Zuma. Ace Magashule, the ANC’s powerful secretary-general, is called “Mr Ten Per Cent” for looting an entire province as a party supremo under Mr Zuma.

The opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) is set to poll about 20%. It was formerly the party of liberal white South Africans, but now it has a young black leader for the first time, Mmusi Maimane. Maimane is integrated into South African big business and the party stands for some limited reforms on land ownership, reducing corruption and crime – all proposals that the ANC stands for too. The DA could attract the small group of middle-class black households disgusted with the corruption of the ANC.

The most radical party is the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a split-off from the ANC led by former ANC youth leader, Julius Malema. The EFF wants the nationalisation of land without compensation and the state take-over of the mines and the central bank. It already has 25 seats in parliament and is likely to poll around 12-14% in this election and increase its representation with backing from radical youth.

South African capitalism in the post-apartheid era has not kept pace with its BRIC peers, particularly China, Russia and India, and is now really a member of the ‘fragile five’ (India, Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa). So Ramaphosa must deal with a stagnant capitalist economy, high levels of poverty, inequality, corruption and crime; and with an economy very vulnerable to a global slump that would expose the external trade deficit that has been growing and would lead to capital flight and rising interest rates.

Widening current account deficit (% of GDP)

A deep economic crisis is a very real prospect for the ANC government over the next five years.

No comments:

Post a Comment