Indonesia has a general election today. For the first time in Indonesian history, the president, the vice president, and members of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), will be elected on the same day with over 190 million eligible voters – that’s the largest single day electorate in the world (India votes over a whole month.

In the presidential election, incumbent Indonesian President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, will run for re-election with senior Muslim cleric Ma’ruf Amin as his running mate against former general Prabowo Subianto and former Jakarta deputy governor Sandiaga Uno for the five-year term between 2019 and 2024. The election will be a re-match of the 2014 presidential election, in which Widodo defeated Prabowo.

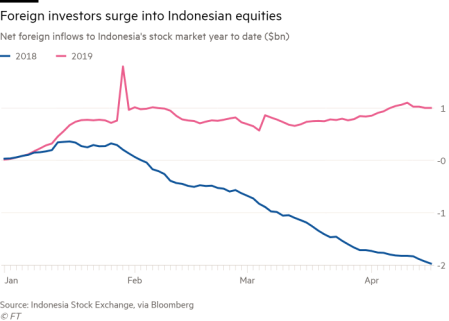

The opinion polls suggest that the incumbent Jokowi will be re-elected. International capital will like that – if only because they can rely on Jokowi to support foreign investment with incentives and sustain a ‘steady’ policy for the currency and public finances. In expectation of the Jokowi victory, foreign investors have poured into the Indonesian stock market in the first two months of 2019.

Prabowo has adopted a nationalist, hardline conservative Muslim campaign that does not appeal to foreign capital. Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim country. It has the largest economy in Southeast Asia, is a member of the G20 top economies, and is the 11th largest economy in the world by nominal GDP. But by GDP per capita, it is ranked only 115th in the world where China is 67th, or just 6% of that of the US.

So what is the state of the Indonesian economy as the election starts? Here, I would appreciate the help of any blog readers from Indonesia or other Asian states for their opinion as it is always difficult to gauge things properly from afar. But anyway, here goes.

Indonesia is very much a fossil fuel economy with oil and gas predominate, despite some development of manufacturing. Agriculture is a key sector which contributes 14% of Indonesia’s GDP. Indonesia is the world’s biggest producer of palm oil, providing about half of the world’s supply. The rapacious drive to farm palm oil has already destroyed much of the natural habitat of the country and the living of many peasant farmers.

From the point of view of the vast majority of Indonesians, Jokowi has disappointed. In winning the election in 2014, Jokowi aimed to match the economic growth seen in China and India, but has fallen well short of his growth target of 7% in his first term. Average growth has been about 5% a year in the last five years and, given the current global slowdown, that rate is likely to slow further. And when population growth is taken into account, real GDP per capita will only rise by less than 4% over the next few years, even if there is no global recession. Sure, that is a good rate of growth by the standards of advanced capitalist economies, but nowhere near enough to lift the economy beyond what the World Bank likes to call ‘middle-income’ levels.

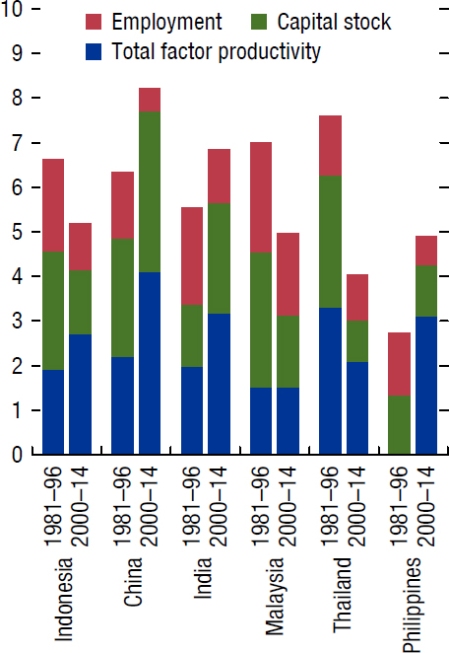

Indonesia’s economic growth has slowed in the past decade, with the contributions from capital and labour falling and that of TFP (innovation), remaining below its peers. Indonesia still trails the performance of China and India, at least in GDP terms, by some way. It is likely to fail to break out of the category of a ‘middle-income’ economy for the foreseeable future.

Slower growth has made it more difficult to create quality jobs for the nearly 2 million new labour force entrants each year. Jokowi aims to create 100 million jobs in the next five years in an economy where more than half the population of 260 million are under the age of 40. The jobless rate is near a 20-year low of 5.3%, which looks good on paper, but hides a growing problem of underemployment. The number of people working less than 35 hours a week has been increasing. Almost 36 million people, near close to a third of the workforce, are classed as underemployed, according to official statistics.

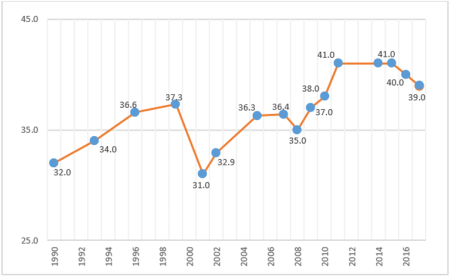

While the poverty rate (as defined by the World Bank) has fallen by half since 1999, this is an illusion. The gap between rich and poor has grown faster in Indonesia than in any other country in Southeast Asia. An Oxfam report on inequality in Indonesia found its four richest men now have more wealth than 100 million of the country’s poorest people. According to Asia Wealth Report, Indonesia has the highest growth rate of high-net-worth individuals (HNWI) predicted among the 10 most Asian economies. This is reflected in the country’s Gini index – which measures inequality from 0 (perfect equality) to 100 (perfect inequality). World Bank estimates reveal that Indonesia’s Gini index increased to 39.0 in 2017 from 30.0 in the 1990s.

The Wealth Report 2015 by Knight Frank reported that in 2014 there were 24 individuals with a net worth above US$1 billion. Indeed 1% of Indonesia’s population have 49.3% of the country’s $1.8 trillion wealth. In contrast, approximately 1 in 3 children under the age of 5 in Indonesia suffer from stunting which reflects impaired brain development that will affect the children’s future opportunities.

Economic growth has not been evenly spread – as is usual in any capitalist economy. In an archipelago of more than 17,000 islands that spans the equivalent distance of New York to London, the island of Java, home to the capital Jakarta, accounts for almost 60% of Indonesia’s annual gross domestic product. While Jakarta’s economy grew 6.4 % last year, the country’s easternmost province of Papua (annexed in a war by the Indonesian generals) contracted about 17.8%.

Jakarta is one of the most densely populated cities on Earth, so Jokowi has been striving to boost infrastructure projects to cope. But Indonesia is way behind compared to the efforts of China. Indonesia finally saw its first underground rail line open in March. But by relying on foreign capital and markets to fund projects, the widely proclaimed infrastructure plan of $350bn by 2025 is falling well short.

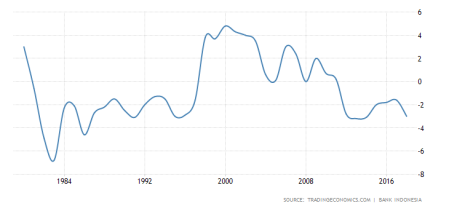

One problem is that the rich, as in many so-called emerging capitalist economies, do not pay much tax – tax revenues are just 11.5% of GDP. As a result, domestic savings and resources remain in the hands of the rich, forcing the government to borrow to invest. The external deficit has been rising as a result, putting pressure on the currency, the rupiah. The current deficit reached $8.5bn in 2018, or 3.5% of GDP.

This makes Indonesia reliant on foreign capital to fund its import needs, inflows that can be volatile as investor sentiment swings. In past global financial crises, Indonesia has been put in the camp of the ‘fragile five’ large emerging economies vulnerable to global capital flight. Indonesia was targeted in an emerging market sell-off last year, triggered by rising US interest rates and a stronger dollar. The rupiah slumped more than 5% against the dollar in 2018, dropping to its lowest levels since the Asian financial crisis two decades prior, as investors pulled out of the nation’s stocks and bonds. Indonesia’s main export markets are China, US and Japan; so any downturn there will severely affect the ability to finance growth.

The international agencies and foreign capital want Indonesia to carry out ‘neoliberal’ reforms as their solution to raising productivity and the growth rate. Jokowi is not going fast enough in doing this. “Jokowi has continued to shy away from the tough reforms that are needed to boost the country’s long-run prospects,” said Gareth Leather, senior Asia economist at research consultancy Capital Economics. “In particular, the president has made no progress on freeing-up Indonesia’s rigid labour market,” Leather wrote in a recent note. “So long as it remains extremely difficult to hire and fire workers, it will be very hard for Indonesia to develop the sort of labour-intensive manufacturing base that has underpinned the economic success of other countries in the region.” Give us cheap labour and all will be well.

The IMF wants the government to divest itself of state enterprises in key sectors of the economy. As the IMF put it in a recent report on the country: “The dominant role of SOEs (state enterprises) needs to be reduced. Even though assets have risen to about 50% of GDP and revenue is stable, SOE efficiency declined through 2015. This suggests SOEs have increased their non-commercial activities and are receiving implicit subsidies, including through price controls (for example, on gas, electricity, airfares, and the retail prices of various products) and import and export restrictions. These practices could undermine the financial strength of SOEs, increase fiscal risks from contingent liabilities, and crowd out private investment.”

Yes, the problem is that the state sector could ‘crowd out’ the privately owned corporate sector. But then the latter won’t invest in the infrastructure necessary for more inclusive growth and won’t pay taxes to fund such investment.

Which way will Jokowi go?

No comments:

Post a Comment