I don’t really like the term ‘neoliberal’ because it is used lazily as an alternative to pro-capitalist policies or even to the word ‘capitalism’ itself. In doing so, it causes confusion in explanations about trends and failures in capitalist development. What flows is the argument that if ‘neoliberalism’ is ended, then we can return to ‘managed capitalism’ or social democracy’, neither of which, in my view, should be used to suggest something different from the capitalist mode of production itself.

And if leftists continue to use ‘neoliberalism’ as a term to replace capitalism (or as some nasty ‘free market version), they open the door to the sort of nonsense that economic journalist Noah Smith concocted last week, as expressed in his Bloomberg piece: “Neoliberalism should not be a dirty word on the left”.

In his piece, Smith argues that by attacking neoliberalism,“Too many people forget the contribution markets have made to human well-being.” He justifies the success of neoliberalism (as defined by him as capitalist market forces and policies that support such) with three main stylised facts.

The first is that “Market liberalization in countries such as India and China seems to have precipitated a shift to faster growth, while trade and investment links with rich countries have helped these and other developing countries tremendously.” So China’s growth miracle is a product of neoliberal policies of ‘market liberalisation’, presumably introduced by Deng in the late 1970s and supplemented by foreign investment and China joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

This story has been perpetuated by many mainstream economists. But it does not hold water. Yes, China opened up sectors of the economy to foreign investment and the market, particularly in agriculture. But the bulk of investment and foreign trade was still controlled by the state and state corporations; and capital controls were in force. The state was everywhere in the operation of the economy. So was China’s success really a product of neoliberalism? See my post on this misconception here.

The second argument is that neoliberal policies have “helped pull a billion people out of desperate poverty, and billions more are on the way to becoming middle class.” This is yet another myth offered by the apologists for global capitalism by the likes of Microsoft billionaire, Bill Gates, among others. Smith follows in those footsteps to justify ‘neoliberalism’.

Anthropologist Jason Hickel has provided an excellent refutation of this claim that global poverty is being solved and falling fast, thanks to capitalism. Much depends on how to define poverty. Hickel: “If we use $7.40 per day, we see a decline in the proportion of people living in poverty, but it’s not nearly as dramatic as your rosy narrative would have it. In 1981 a staggering 71% lived in poverty. Today it hovers at 58% (for 2013, the most recent data). Suddenly your grand story of progress seems tepid, mediocre, and – in a world that’s as fabulously rich as ours – completely obscene…. “And if we look at absolute numbers, the trend changes completely. The poverty rate has worsened dramatically since 1981, from 3.2 billion to 4.2 billion, according to World Bank data. Six times higher than you would have people believe. That’s not progress in my book – that’s a disgrace.”

In his pursuit of praise for neoliberalism (in reality capitalism) Smith has elsewhere tried to trash Hickel’s arguments that global poverty has not really declined. But, as usual, Smith and others who take his line, ignore the key fact that the fall in global poverty levels, whatever the threshold points chosen, is mostly down to the massive reduction in poverty levels in China – a country that can hardly be considered having an economy that operates on neoliberal free market forces (although Smith seems to claim it does!).

Of the billion that Smith cites, there are over 800m Chinese who have been taken above the poverty threshold in the last 30 years. Sanjay Reddy looked at the poverty data excluding China. He found “modest decreases in total poverty headcount or even increases, sometimes sizable, especially at higher poverty lines & over longer periods, more marked in certain regions.”

Smith supplements his argument for neoliberalism by arguing that in the last 30 years “progress in the developing world has been impressive — something for which neoliberalism probably deserves a lot of credit — but it is far from complete; most of South Asia is still very poor, and much of Africa is just beginning to industrialize.” Indeed, far from complete. The inhabitants of Nigeria, Africa’s most populated country or those of the Congo can tell Smith that progress in their countries has not been “impressive” at all. And not just there. According to Ha-Joon Chang, a Cambridge economist, during the 1960s-and-70s per capita income in Sub-Saharan Africa was around 1.6% per annum; however, after they were imposed with a neoliberal economic model by the West, during the 1980s and 90s, per capita income fell to only 0.7% per year.

What industrialisation that has taken place in recent decades (beyond just basic resource and agro commodity production) in Africa is mainly due to the investment being offered and applied by China – the opposite of Smith’s model of neoliberalism, in my view.

Smith also argued that “neoliberal policies might have led to faster productivity growth in the 1990s and early 2000s” in the advanced capitalist economies. You see “The spurt of growth is commonly attributed to the information-technology boom, but that boom might not have been possible if the US had more strictly regulated emerging industries in order to protect favored incumbents.” This is just speculation without evidence. Whatever “spurt” in productivity took place in the hi-tech boom of the 1990s, it was still way less than in the pre-neoliberal period of the 1950s and 1960s (see graph).

Moreover, it has been the state that has sparked much of that ‘innovation’ back in the 1960s and after, Mariana Mazzacuto, in her book, The Entrepreneurial State, explains that” the real story behind Silicon Valley is not the story of the state getting out of the way so that risk-taking venture capitalists – and garage tinkerers – could do their thing. From the internet to nanotech, most of the fundamental advances – in both basic research but also downstream commercialisation – were funded by government, with businesses moving into the game only once the returns were in clear sight. All the radical technologies behind the iPhone were government-funded: the internet, GPS, touchscreen display, and even the voice-activated Siri personal assistant.”

Contrary to Smith’s neoliberal view, state-owned industry and economic growth often go together – “the seldom-discussed European success story is Austria, which achieved the second highest level of economic growth (after Japan) between 1945 and 1987 with the highest state-owned share of the economy in the OECD.” (Hu Chang).

Smith claims neoliberal reforms in the labour market helped to achieve lower unemployment rates in places like Germany. “Germany suffered high unemployment in the 1980s and 1990s, thanks to its rigid labour market regulations; eventually, it eased those restrictions, which

substantially lowered the unemployment rate.”

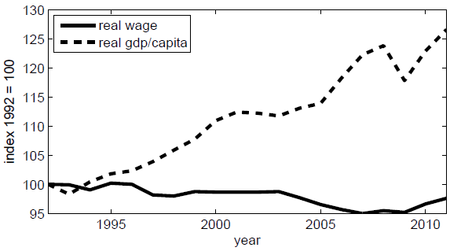

Here he refers to the infamous Haartz labour reforms that introduced a tiered employment system, putting millions into low wage programmes that boosted German industry’s profitability while keeping real wage incomes stagnant.

About one quarter of the German workforce now receive a “low income” wage, using a common definition of one that is less than two-thirds of the median, which is a higher proportion than all 17 European countries, except Lithuania. A recent Institute for Employment Research (IAB) study found wage inequality in Germany has increased since the 1990s, particularly at the bottom end of the income spectrum. The number of temporary workers in Germany has almost trebled over the past 10 years to about 822,000, according to the Federal Employment Agency. In my view, this is not the best example of the ‘success’ of neoliberal policies, at least not for labour.

It is ironic that Smith pushes the policies of the ‘free market’ at a time when all the trends in the current neoliberal world show slowing growth in real GDP, productivity and investment, along with stagnant real wages and rising inequality.

And yet, Smith presses on with the argument for neoliberal policies to “restrain social democrats’ more ambitious impulses” and “to protect the US economy’s entrepreneurial private sector, and to make sure that technological progress and international trade don’t get forgotten.” In other words, he reckons that we need to balance, against the urgent need for decent public services, proper labour rights and conditions, control of the corrupt and unproductive finance sector and the avoidance of disastrous economic slumps, the fundamental (neoliberal) aim to raise the profitability of the capitalist sector.

Because we must not ‘forget’ the “contribution of markets to human well-being.”

No comments:

Post a Comment