Today is a threshold date for the global economy. Trump’s US administration starts imposing trade tariffs on $34bn of imports from China. And Beijing is set to target an equal amount in retaliation. Add that to the pile of tariffs and counter-tariffs growing across the Atlantic and North America, and the value of trade covered by the economic wars that Trump has launched will race through the $100bn mark by today.

And that’s just the beginning. This escalating trade war could easily surge through the trillion-dollar mark, taking 1.5% of global GDP. It would be equivalent to a quarter or more of the US’s $3.9tn total trade with the world last year and at least 6% of global merchandise trade (worth $17.5tn in 2017, according to the World Trade Organization).

The $34bn in Chinese imports being targeted by the Trump administration today are roughly equivalent in value to a month of imports from China. In this tranche, a 25% import tax will be applied on 818 products ranging from water boilers and lathes to industrial robots and electric cars. In return, Beijing charge a similar tariff on a list that includes soya beans, seafood and crude oil. Both countries have also issued further product lists that would take the total trade covered to $50bn on each side.

Angered by China’s retaliation, Trump has ordered a further $200bn worth of imports to be targeted for a 10% tariff and threatened to go for another $200bn beyond that. To which Beijing has vowed its own response. US imports from China were worth $505bn last year while US exports to China reached a record $130bn. So a £450bn rise in tariffs will sweep across much of China’s imports. The Trump auto wars could be worth even more than $600bn. In a televised interview on Sunday the US president called his plan to impose tariffs on imported cars and parts in the name of US national security “the big one”. And that is certainly how the EU and others see it. According to official data, the US imported $192bn in cars and light trucks in 2017 and a further $143bn in parts for a total of $335bn.

Then there’s NAFTA. The US trades more with Canada and Mexico ($1.1tn) than it does with China, Japan, Germany and the UK combined. Trump is seeking to renegotiate it just as a leftist and nationalist President AMLO has been elected in Mexico. Trump seems to believe the auto tariffs will give him leverage over the EU and Japan in trade negotiations as well as over Canada and Mexico in the continuing talks over an updated North American Free Trade Agreement. Mr Trump is dialling up the pressure to force capitulation. For that reason, the US could impose 20% tariffs on some or all of those imports.

Then there is FART. Trump is planning a bill through Congress, called the Fair and Reciprocal Tariff Act, or FART for short. FART would allow Trump to abandon the World Trade Organization’s tariff rules, granting him new authority to unilaterally change tariff agreements with certain countries; to abandon central WTO trade rules, namely the “most favoured nation” principle that keeps countries from setting different tariff rates for different countries outside of free trade agreements and “bound tariff rates,” the tariff ceilings that each WTO member country has previously agreed to. In short, it would give Trump the authority to start a trade war without Congressional oversight, all while flouting the WTO’s rules. It would mean the end of the WTO, in essence. Already, at least one prominent Trump backer, Trump’s short-lived communications director Anthony Scaramucci, tweeted that FART “stinks.” But the smell is getting worse.

Any US tariffs are likely to be met with retaliation. EU officials have been working on a plan to target upwards of €10bn in US goods for retaliation if it goes ahead with tariffs on the $61bn in cars and parts it imported from the EU in 2017. But in the extreme scenario — of like-for-like, tit-for-tat tariffs — more than $650bn in global trade would be covered, with consequences for companies globally.

What is the likely impact on global growth from this trade war? Well, Paul Krugman, Keynesian economist, won the Nobel prize in economics for his work on international trade and recently he did a ‘back of the envelope’ calculation. Krugman reckons that “there’s a pretty good case that an all-out trade war could mean tariffs in the 30-60% range; that this would lead to a very large reduction in trade, maybe 70%”! And the overall cost to the world economy would be about a 2-3% reduction in world GDP per year – in effect wiping out more than half of current global growth of about 3-4% a year (and the latter assumes that there is no new global recession).

Krugman reminds us that in the Great Depression of the 1930s, the trade war launched by the US with the Smoot-Hawley tariff, pushed tariffs up to 45%. “So both history and quantitative models suggest that a trade war would lead to quite high tariffs, with rates of more than 40% quite likely.” Remember current global trade tariff rates are about 3-4% only.

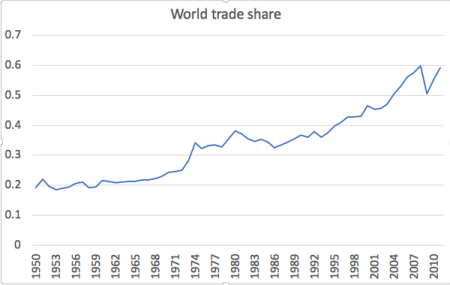

Already, world trade has been staggering from the impact of the Great Recession and the subsequent Long Depression. And world trade share (share of trade in global GDP) has stagnated at about 55% (see figure below). Indeed, the great era of globalisation is over. Now the trade war – another consequence of the Great Recession and the Long Depression since 2008 – could roll back the world trade share to 1950s levels, according to Krugman. ”If Trump is really taking us into a trade war, the global economy is going to get a lot less global.”

Given this, Krugman looked at the hit to US economic growth. He reckoned it could take 2% of GDP off real growth each year. As average growth is expected to be about 2% a year over the next five years (assuming no world slump), that would mean the US economy would stagnate. That is not as bad as the Great Recession, which knocked 6% of US real GDP growth, but it’s bad enough to sustain a further leg of the current Long Depression.

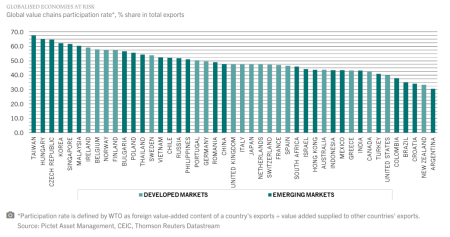

And other countries will be hit even harder. Several major economies rely on trade much more than the US and Europe for growth. In the league of global value chain for trade, Taiwan is top with nearly 70% of value-added coming from exports; and many Eastern European countries also have high export ratios. The US is only at 40% and indeed China is under 50%.

According to Pictet asset management, if a 10% tariff on US trade were fully passed onto the consumer, global inflation would rise by about 0.7%. This, in turn, could reduce corporate earnings by 2.5% and cut global stocks’ price-to-earnings ratios by up to 15%. All of which means global equities could fall by some 15-20%. In effect, this would put world stock market price back by three years – indeed a crash.

Meanwhile, Asian governments, led by China, are continuing their drive to relax trading restrictions among themselves, while retaliating to Trump’s trade war. Last week, the 16-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which includes China, Japan and India but not the US, met in Tokyo to try and complete a new trade pact that would include the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations as well as South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, and cover one third of the world’s economy and almost half its population.

And of course, as I have argued previously, China is driving forward its belt and road global investment scheme across central Asia. So, although many Asian and Eastern European economies may suffer more than the US initially from a global trade war, longer term, trade pathways may alter to make them more Euro-Asia centric, to the detriment of the US and Latin America.

Global growth has been picking up in the last 12 months after a near-recession in 2015-16. Indeed, Gavyn Davies, FT economics blogger and former Goldman Sachs chief economist, reckoned that world growth was growing at 4.4%, about 0.6% above trend, and a full percentage point higher than a couple of months ago.

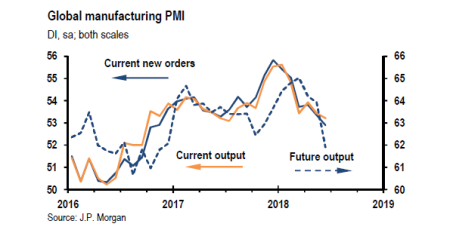

But the trade war will particularly hit the manufacturing and productive sectors of the major economies. And while global growth as a whole may have picked up recently, world manufacturing growth is looking frail. The global manufacturing PMI measures activity in manufacturing and anything over 50 means growth. So not looking so rosy.

Indeed, the US stock market has not bounced very much because, counteracting the one-off rise in corporate profits, has been the possibility of rising interest rates driving up the cost of borrowing and servicing existing debt and the potential hit from the coming trade war.

Hopes for a sharp rise in productive investment from the tax cuts appear dashed. Instead of more investment, there has been a three-fold increase ($150bn) is share buybacks. In Q1 alone, US corporations collectively repatriated $217bn of their international stashes, around 10% of the $2.1trn of greenbacks estimated to be currently offshore. But JPMorgan calculates only $2bn of the $81bn repatriated in Q1 by the top 15 companies was spent on productive investment.

World economic growth (and US growth may have peaked in Q2 2018 and now there is the prospect of an all-out trade war.

No comments:

Post a Comment