The recent workshop on China organised by the China Workshop (poster and programme_05062018) in London asked all the questions, even if it did not resolve them. What are the reasons for China’s phenomenal growth in the last 40 years and can it last? What is the nature of the Chinese economy: is it capitalist or not? What explains under Xi the new emphasis on studying Marxism in China’s universities? Is China’s export and investment expansion abroad imperialist or not? How will the trade war between the US and China pan out?

In the opening session, Dr Dic Lo, Reader in Economics at SOAS, London University and Zhu Andong, Vice Dean at the School of Marxism at Tsinghua University, Beijing (representing a delegation from various Chinese universities) were at pains to argue that China is misrepresented in the so-called West and not just through mainstream capitalist views but also from the left.

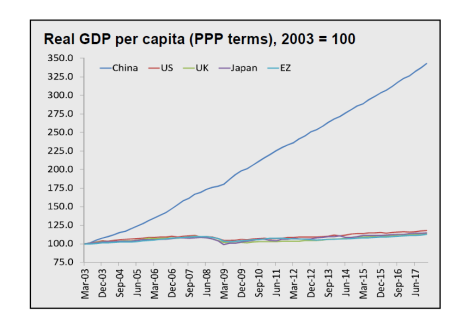

All the talk from the left, said Lo, was about political repression, labour exploitation, inequality or Chinese ‘imperialism’. But then how to explain China’s phenomenal growth and success in taking over 850m people out of poverty (as defined by the World Bank) and reaching national output second only to the US. China doubles real living standards every 13 years. It now takes the US and Europe 50 years and Japan even longer. Is this just fake or illusory and if not, how can this ‘capitalist’ and ‘imperialist’ economy have bucked the trend, when the record of all other capitalist economies (advanced or ‘emerging’) can show no such success? “How can it be possible, in our times, for a late-developing nation to move up the world political-economic hierarchy to become imperialist? Can anyone on the left answer this question?”

Dic Lo criticised the majority view of left political economists that China could be characterised as “neoliberal capitalist”, the so-called “Foxconn Model” of labour exploitation. This view was pioneered by Martin Hart-Landsberg and Paul Burkett, made most influential by David Harvey, most systematic by Minqi Li; and politically correct by Pun Ngai. But were they right?

Zhu Andong also critiqued what he considered was this Western view. In contrast, far from a Marxist critique disappearing in China, there was growing official support for the study of Marxism in Chinese universities, both in special departments and even increasingly in economics departments, which up to recently had been dominated by mainstream neoclassical economics influenced by Western universities.

In my contribution, I also referred to the dominance of mainstream economic analyses on the nature of China – and such theories also still appeared in China’s own financial institutions like the People’s Bank of China. A recent striking example is Wang Zhenying, director-general of the research and statistics department at the PBoC’s Shanghai head office and vice chairman of the Shanghai Financial Studies Association. For Wang, Marx has had his day in the theoretical limelight (ie 19th century) and for that matter so had Keynes (20th century). The recent global financial crisis needs a new theory for the 21st century. And this apparently was the behavourial economics of ‘uncertainty’, not Marx.

I argued that there are really three models of development that could explain China’s growth miracle and whether it would last. I deal these in detail in my paper on China for the Leeds IIPPE conference in 2015. So please consult that for a fuller account than this post can provide. https://thenextrecession.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/china-paper-july-2015.pdf

There is the mainstream neoclassical view that: China went through a primitive industrial expansion using its ‘comparative advantage’ of cheap and plentiful labour and investment in heavy industry.

But now China had reached the ‘Lewis point’ (named after the left economist of the 1950s, Arthur Lewis). Put simply, this is the point at which a developing country stops being able to achieve rapid growth relatively easily, by simply taking rural workers doing unproductive farm labour and putting them to work in factories and cities instead. But once this ‘reserve army of labour’ is exhausted, urban wages rise, incomes reach a certain level and a middle-class emerges. China is now in a ‘middle-income’ trap like many other emerging economies, from which it cannot escape and become an advanced economy, unless it gets rid of state enterprises and heavy industry and orients towards the consumer and services.

This view is nonsense for several reasons – not least because comparative advantage theory is bogus and unrealistic – after all, China has grown exponentially not just because of cheap labour but also because of massive productive investment promoted and controlled by the state sector. Actually, as a result of that investment expansion, consumption spending is also growing very fast. Would a switch to capitalist companies serving a middle-class consumer be better?

The second model is the Keynesian. This recognises that China’s success has been due to massive investment in productive capital, not just the use of cheap labour. Infrastructure investment directed and controlled by the state was behind the ability of the Chinese economy to avoid the worst effects of global financial crash and the Great Recession where every other economy suffered. But what the Keynesian model fails to recognise is that China cannot escape the law of value and imbalances and inequalities that value creation through trade and the growing market economy generates.

The Marxist analysis starts from the basic premise that human social organisation aims to raise the productivity of labour to the point that sufficient abundance will make it possible for toil and poverty to be eliminated. But the drive for higher productivity in capitalism comes into conflict with capital’s requirement for profitability. Increasingly, the issue for China is whether the capitalist sector of the economy will eventually override the planned public sector, so that profitability will dominate over productivity and crises will appear, leading to stagnation not expansion.

In my view, that point has not yet been reached in China. The state sector and public investment through one-party dictatorship still control investment, employment and production decisions in China – the private capitalist sector, although growing, is still subject to that control. See my post here.

Now this is a minority view among Marxian economists, let alone mainstream economics. Most consider that China is capitalist just like any other capitalist economy, if with a bit more state intervention. Indeed, it is even imperialist in the Marxist sense. But, as I have shown in previous posts, 102 big conglomerates contributed 60 per cent of China’s outbound investments by the end of 2016. State-owned enterprises including China General Nuclear Power Corp and China National Nuclear Corp have assimilated Western technologies—sometimes with cooperation and sometimes not—and are now engaged in projects in Argentina, Kenya, Pakistan and the UK. And the great ‘one belt, one road’ project for central Asia is not aimed to make profit. It is all to expand China’s economic influence globally and extract natural and other technological resources for the domestic economy.

This also lends the lie to the common idea among some Marxist economists that China’s export of capital to invest in projects abroad is the product of the need to absorb ‘surplus capital’ at home, similar to the export of capital by the capitalist economies before 1914 that Lenin presented as key feature of imperialism. China is not investing abroad through its state companies because of ‘excess capital’ or even because the rate of profit in state and capitalist enterprises has been falling.

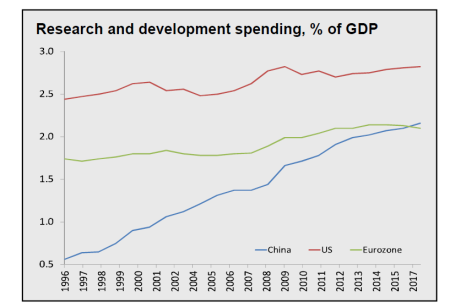

Indeed, the real issue ahead is the battle for trade and investment globally between China and the US. The US is out to curb and control China’s ability to expand domestically and globally as an economic power. At the workshop, Jude Woodward, author of The US vs China: Asia’s new cold war?, outlined the desperate measures that the US is taking to try to isolate China, block its economic progress and surround it militarily. But this policy is failing. Trump may have launched his tariff hikes, but what really worries the Americans is China’s progress in technology. China, under Xi, aims not just to be the manufacturing centre of the global economy but also to take a lead in innovation and technology that will rival that of the US and other advanced capitalist economies within a generation.

There was a theoretical debate at the workshop about whether China was heading towards capitalism (if not already there) or towards socialism (in a gradual way). Marx’s view of socialism and communism was cited (from Marx’s famous Critique of Gotha Programme) with different interpretations. For me, I reckon Marx’s view of socialism and/or communism starts from two realistic premises; 1) that communism as a society of super-abundance where toil, exploitation and class struggle have been eliminated to free the individual, is technically possible now – especially with the 21st technology of AI, robots, internet etc; and 2) socialism and/or any transition to communism cannot even start until the capitalist mode of production is no longer dominant globally and instead workers’ power and planned democratically-run (not dictatorships) economies dominate. That means China on its own cannot move (even gradually) to socialism (even as the first stage towards communism) unless the dominant power of imperialism is ended in the so-called West. Remember China may be the second-largest economy in the world in dollar terms but its labour productivity is less than one-third of the US.

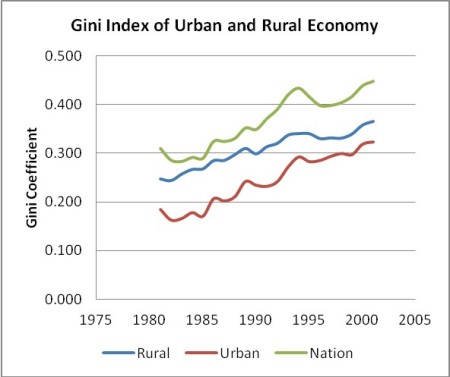

China has succeeded in transforming its economy and society since the revolution of 1949 by the removal of capitalist and imperialist power and through state control of the commanding heights of industry and agriculture. And it is now succeeding in applying new technology to take it forward as a modern urbanised society in this century. But at the same time, the law of value and capitalism operates within the country. Indeed, the capitalist sector in the economy is growing; there are many more Chinese billionaires and inequality of income and wealth has risen; while Chinese labour struggles against exploitation in the workplaces. And the law of value exerts its destructive influence also through international, trade, multi-national companies and capital flows – it was no accident that when China last year relaxed its capital controls on the advice of neoliberal elements in the monetary institutions that the economy suffered serious capital flight.

There is a (permanent) struggle going on within the political elite in China over which way to go – towards the Western capitalist model; or to sustain “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. After the experience of the Great Recession and the ensuing Long Depression in the West, the pro-capitalist factions have been partially discredited for now. President for Life Xi now looks to promote ‘Marxism’ and says state control (through party control) is here to stay. But the only real way to guarantee China’s progress, to reduce the growing inequalities and to avoid the risk of a swing to capitalism in the future will be to establish working class control over Chinese political and economic institutions and adopt an internationalist policy a la Marx. That is something that Xi and the current political elite will not do.

No comments:

Post a Comment