There are two new mainstream papers out that offer some interesting analysis on the reasons behind the Long Depression that the major economies (or at least, the US) have suffered since the end of the Great Recession in 2009 – in the growth of real GDP, productivity, investment and employment.

First, there is a paper by economists at the San Francisco Federal Reserve.

The Disappointing Recovery in U.S. Output after 2009 by John Fernald, Robert E. Hall, James H. Stock, and Mark W. Watson. They consider the well-known evidence that US real GDP growth has expanded only slowly since the recession trough in 2009, counter to normal expectations of a rapid cyclical recovery. In the paper, they remove the “cyclical effects” of the Great Recession and find that there was already a sharply slowing trend in underlying growth before the global financial crash in 2008. The Fed economists conclude that the slowing trend reflected two factors: slow growth of innovation and declining labour force participation.

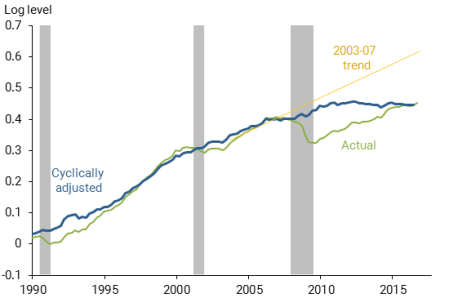

Figure 1 shows business-sector output per person in recent decades. The green line shows that output per person fell sharply during the recession and remains below any reasonable linear trend line extending its pre-recession trajectory. The figure shows one such trend line (yellow line), based on a simple linear extrapolation from 2003 to 2007.

Figure 1

Output per capita: Deep recession plus a sharp slowing trend

The blue line in Figure 1 shows the resulting estimate of trend output per capita after removing the cyclical effects associated with the deep recession. As expected, the cyclical adjustment removes the sharp drop in actual output associated with the recession. But since then, the trajectory of the blue line is nowhere close to a straight line projection from the 2007 peak. Rather, cyclically adjusted output per person rose slowly after 2007 and then plateaued in recent years.

The Fed economists reckon that the slow growth has been due to a slowdown in the productivity of labour, which in turn has been caused by a reduction in investment in innovation and new technology. In mainstream economics, this is measured by the residual of output per person left over after increases in employment (labor input) and means of production (capital input) are accounted for. The residual is called total factor productivity (TFP), to designate the increased productivity per unit of total input. TFP supposedly captures the productivity benefits from formal and informal research and development, improvements in management practices, reallocation of production toward high productivity firms, and other efficiency gains.

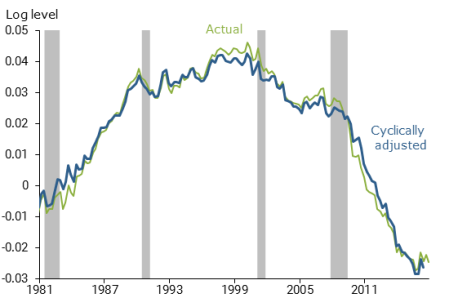

The Fed economists, using this factor accounting, find that TFP growth slowed significantly even before the Great Recession. It picked up in the mid-1990s and slowed in the mid-2000s—before the recession—and then was flat or even falling going into the recession.

Figure 2

Pre-recession slowdown in quarterly TFP growth

The economists dismiss the arguments that it was the Great Recession that caused the productivity slowdown or that productivity growth from info tech is being mismeasured: “such mismeasurement has long been present and there’s no evidence it has worsened over time.” They also dismiss the idea common from right-wing neoclassical economists that “increased regulatory burdens have reduced the economy’s dynamism.” They find no link between regulation changes and TFP growth.

The explanation they fall back on is the one presented by Robert J Gordon in many papers and books: that TFP growth is really just back to normal and what was abnormal was the burst in innovation in the 1990s with the hi-tech and dot.com boom. That ended in 2000 and won’t be repeated. “Every story in the late 1990s and early 2000s emphasized the transformative role of IT, often suggesting a sequence of one-off gains—reorganizing retailing, say. Plausibly, businesses plucked the low-hanging fruit; afterward, the exceptional growth rate came to an end.”

The other factor in the slowdown was the decline in employment growth of those of working age. Yes, there is supposed to be near ‘full employment’ now in the US and the UK etc. But participation in employment by working age adults has fallen sharply. That’s because populations are getting older and the ‘baby boomers’ who started worked in the 1960s and 1970s are now retiring and not being replaced.

Figure 3

Sharp declines in labor force participation rate

What the Fed economists want to tell us is that the Long Depression is not just the leftover of the Great Recession but reflects some deep-seated underlying slowdown in the dynamism of the US economy that is not going to correct through the current small economic upturn. The US economy is just growing more slowly over the long term.

What the Fed economists don’t explain is why the US economy has been slowing in productivity growth and innovation since 2000. What is missing from the analysis is what drives the adoption of new techniques and labour-saving equipment. Gordon and others just accept the current slowdown as a ‘return to normal’ from the exceptional 1990s.

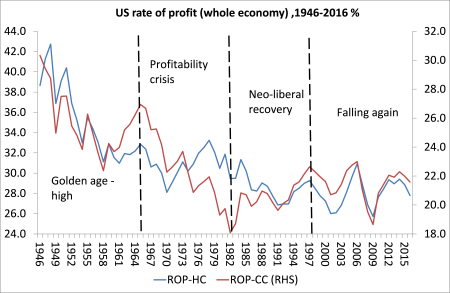

What is missing is the driver of investment under capitalism: profitability. Marxian studies that concentrate on this aspect reveal that the profitability of US capital stock and new investment peaked around 1997 and then turned down. It was this fall in profitability that eventually provoked the collapse in the dot.com bubble in 2000. The subsequent recovery in profitability did not achieve anything better than 1997 and indeed profits growth was mainly confined to the financial sector and increasingly to a small sector of top companies. Average profitability remained flat or even down and the growth in profit was mainly fictitious (‘capital gains’ from real estate, bond and stock markets) and fuelled by easy credit and low interest rates. That house of cards collapsed in the Great Recession.

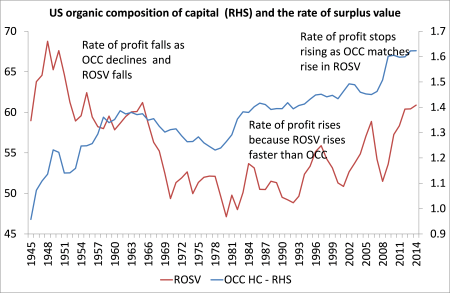

Profitability peaked in the late 1990s in the US (and elsewhere for that matter) because the counteracting factors to Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (a rising rate of exploitation in the neoliberal period) and increased employment to boost total new value were no longer sufficient to overcome a rising organic composition of capital from the tech boom of the 1990s.

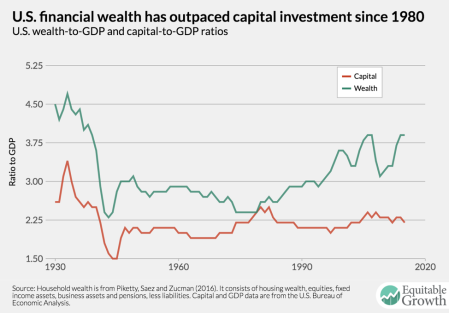

In contrast to this scenario, the Keynesians/post Keynesians have been pushing a different explanation for the fallback in productive investment since 2000 – it’s the growth of ‘monopoly power’. There have been several studies arguing this in recent years. Now a brand new paper by Keynesian economists at Brown University seeks to do the same. Gauti Eggertsson, Ella Getz Wold etc claim that the puzzle of the huge rise in profits for the top US companies alongside slowing investment in productive sectors can be explained by an increase in monopoly power and falling interest rates.

The Brown University economists argue that an increase in firms’ market power leads to an increase in monopoly rents; economic parlance for profits in excess of competitive market conditions-and thus an increase in the market value of stocks (which hold the rights to these rents). This leads to an increase in financial wealth and to what’s known as Tobin’s Q, the ratio of a firm’s financial value (market capitalization) to the value of its assets (book value).

With an increase in market power, the share of income consisting of pure rents increases, while the labour and capital shares both decrease. Finally, the greater monopoly power of firms leads them to restrict output. In restricting their output, firms decrease their investment in productive capital, even in spite of low interest rates.

Now I have dealt previously in detail with this argument that it is increased monopoly power that explains the gap between profits and investment in the US since 2000 or so. It is really a modification of neoclassical theory. Neoclassical theory argues that if there is perfect competition and free movement of capital, then there will be no profit at all; just interest on capital advanced and wages on labour’s productivity. Profit can only be ‘rent’ caused by imperfections in markets. The Brown professors, in effect, accept this theory. They just consider that, currently, ‘monopoly power’ is distorting it. This implies that if there was competition or monopolies were regulated’ all would be well. That solution ignores the Marxist view that profits are not just ‘rents’ or ‘interest’ but surplus value from the exploitation of labour.

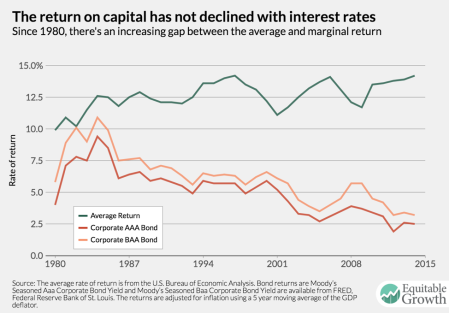

The Brown University professors reckon that average profitability was constant from 1980 onwards, so increased profits must have come from the gap between profitability and the fall in the cost of borrowing (interest rates). But actually, you can see from their graph that average profitability rose from about 10% in 1980 to a peak in the late 1990s of 14% – that’s a 40% rise and is entirely compatible with estimates by me and other Marxist economists. Average profitability was then flat from 200 or so.

Indeed, average profitability fell in the non-financial productive sectors of the economy, which is probably the reason for the gap that developed between overall profitability including financial profits (which rocketed between 2002 and 2007) and net investment in productive sectors.

The jump in corporate profits (yes, mainly concentrated in the banks and big tech companies) was increasingly fictitious, based on rising stock and bond market prices and low interest rates. The rise of fictitious capital and profits seems to be the key factor after the end of dot.com boom and bust in 2000.

As I showed in a previous post, these mainstream analyses use Tobin’s Q as the measure of accumulated profit to compare against investment. But Tobin’s Q is the market value of a firm’s assets (typically measured by its equity price) divided by its accounting value or replacement costs. This is really a measure of fictitious profits. Given the credit-fuelled financial explosion of the 2000s, it is no wonder that net investment in productive assets looks lower when compared with Tobin Q profits. This is not the right comparison. Where the financial credit and stock market boom was much less, as in the Eurozone, profits and investment movements match.

It may well be right that, in the neo-liberal era, monopoly power of the new technology megalith companies drove up profit margins or markups. The neo-liberal era saw a driving down of labour’s share through the ending of trade union power, deregulation and privatisation. Also, labour’s share was held down by increased automation (and manufacturing employment plummeted) and by globalisation as industry and jobs shifted to so-called emerging economies with cheap labour. And the rise of new technology companies that could dominate their markets and drive out competitors, increasing concentration of capital, is undoubtedly another factor.

But the recent fall back in profit share and the modest rise in labour share since 2014 also suggests that it is a fall in the overall profitability of US capital that is driving things rather than any change in monopoly ‘market power’. Undoubtedly, much of the mega profits of the likes of Apple, Microsoft, Netflix, Amazon, Facebook are due to their control over patents, financial strength (cheap credit) and buying up potential competitors. But the mainstream explanations go too far. Technological innovations also explain the success of these big companies.

Moreover, by its very nature, capitalism, based on ‘many capitals’ in competition, cannot tolerate indefinitely any ‘eternal’ monopoly; a ‘permanent’ surplus profit deducted from the sum total of profits which is divided among the capitalist class as a whole. The battle to increase profit and the share of the market means monopolies are continually under threat from new rivals, new technologies and international competitors.

The history of capitalism is one where the concentration and centralisation of capital increases, but competition continues to bring about the movement of surplus value between capitals (within a national economy and globally). The substitution of new products for old ones will in the long run reduce or eliminate monopoly advantage. The monopolistic world of GE and the motor manufacturers in post-war US did not last once new technology bred new sectors for capital accumulation. The world of Apple will not last forever.

‘Market power’ may have delivered ‘rental’ profits to some very large companies in the US over the last decade (and just that short period it seems), but Marx’s law of profitability still holds as the best explanation of the accumulation process. Rents to the few are a deduction from the profits of the many. Monopolies redistribute profit to themselves in the form of ‘rent’, but do not create profit.

Profits are not the result of the degree of monopoly or rent seeking, as neo-classical and Keynesian/Kalecki theories argue, but the result of the exploitation of labour. The key to understanding the movement in productive investment remains in its underlying profitability, not the extraction of rents by a few market leaders.

The Long Depression is a product of low investment and low productivity growth, which in turn is a product of lower profitability of investment in productive sectors and a switch to unproductive financial speculation (and yes, partly a product of oligopolistic power boosting the big at the expense of the small).

No comments:

Post a Comment