ASSA 2018 is the annual conference of the American Economic Association, drawing together the economics profession in the US to discuss hundreds of papers and debate the key issues and ideas that mainstream economics considers. This year in freezing Philadelphia, there has been an obsession with President Trump, his antics and ‘Trumponomics’ if we can call it that. As Trump launched his latest tirade of weird tweets against a new book outlining his mentally unstable antics, the great and good of America’s mainstream economists considered his economic policies.

And they were worried. Three things gripped the mainstream. The first was the apparent failure of globalisation since the Great Recession; the poor level of productivity growth in the major capitalist economies in the last ten years; and the effectiveness of Trump’s proclaimed protectionist trade policy that he has combined with slashing reductions in taxation on the US corporate sector and his rich elite friends.

It seems that the mainstream is now aware that free trade and free movement of capital that has accelerated globally over the last 30 years has not led to gains for all – contrary to the mainstream economic theory of comparative advantage and competition.

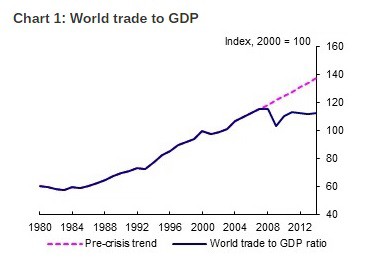

Since the end of the Great Recession, world trade growth has slowed almost to the level of global GDP growth – something unprecedented in the post-1945 period. And cross-border capital flows have declined sharply, particularly bank lending. And then along comes Trump with his threats to end US participation in trade pacts, to slap duties on Chinese imports and run a wall against Mexico etc.

But the other factor about globalisation that has now dawned on the mainstream is that it has increased inequality of wealth and income, both between nations and also within economies as trans-national corporations move their activities to cheaper labour areas and bring in new technology that requires less labour. Of course, this is the basis of Trump’s appeal to those ‘left behind’. The Great Recession, the weak recovery in this Long Depression, the imposition of ‘austerity’ in public sector spending and huge cuts in taxation for the rich has engendered the rise of ‘populism’ ie anti ‘free trade, anti-immigration, anti-deregulation, anti-bankers.

All this is very worrying for the mainstream. Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist of the IMF and one of the great and good who always speaks at the big ASSA meetings, kicked off his analysis of the first year under Trump with a real concern that there was “a large degree of uncertainty about what policies will in the end be adopted. So far, and surprisingly, this policy uncertainty does not seem to have affected economic activity.” Blanchard was relieved but “it is still early to tell”. TheEffectsOfPolicyUncertainty_powerpoint

Edmund Phelps, a Nobel prize winner and economics guru of Columbia University NY, also spoke. He has said in the past that Trump’s ideas were “like economic policy at a time of fascism”. At ASSA he was worried that Trumpean economics has “no awareness that nations at the frontier need indigenous innovation to have ample growth.” What was needed was for the US economy to be opened up for risk-taking, not “stunted economics” that just tries to boost Americans’ wages through protectionism. Phelps was worried that what he called “the post-World War II global economic and political order” (ie free markets, globalisation and the rule of the dollar) was under threat to detriment of all. AmericasPolicyThinkingInTheAgeO_preview

In other sessions, another Nobel prize winner Joseph Stiglitz and Harvard professor Dani Rodrik were less sanguine about the perceived benefits of the last 30 years of globalisation. TrumpAndGlobalization_preview

Rodrik in an opening plenary session reckoned that the problem with unbridled free trade and free movement of capital globally was that it was bound to intensify inequality of income because it often leads to increased “market failures” (another word for crises and slumps). Indeed, ‘compensation’ cannot credibly address the longer-term erosion of distributional bargains entailed in trade agreements and financial globalization.

Stiglitz also argued globalisation and free trade were “not a Pareto improvement” (did not offer equal gains) and so that government intervention would be necessary to right any income imbalances. “While Trump was wrong in claiming that the trade agreements were unfair to the US, there is little doubt that globalization contributed to the weakening of wages of America’s skilled workers. Learning this lesson—if in fact we do—may be the only silver lining in this dark cloud hanging over the global horizon.”

MakingGlobalizationMoreInclusiveWhe_powerpoint

So it seems that, with the rise of Trump and other populists, mainstream economics’ blind faith in ‘free trade’ and free movement of capital as the mantra of capitalist success has been shaken. Of course, Marxist economics could have revealed this outcome of globalisation. David Ricardo’s ‘thought theory’ of comparative advantage has always been demonstrably untrue. Under capitalism, with open markets, more efficient economies will take trade share from the less efficient. So trade and capital imbalances do not tend towards equilibrium and balance over time. On the contrary, countries run huge trade deficits and surpluses for long periods, have recurring currency crises and workers lose jobs to competition from abroad without getting new ones from more competitive sectors (see Carchedi, Frontiers of Political Economy p282).

It is not comparative advantage or costs that drive trade gains, but absolute costs (in other words relative profitability). If Chinese labour costs are much lower than American companies’ labour costs, then China will gain market share, even if America has some so-called “comparative advantage” in design or innovation (contrary to the view of Phelps). What really decides is the productivity level and growth in an economy and the cost of labour.

So far from globalisation and free trade leading to a rise in incomes for all, under the free movement of capital owned by the trans-nationals and free trade without tariff and restrictions, the big efficient capitals triumph at the expense of the weaker and inefficient – and workers in those sectors take the hit.

Now the mainstream has woken up to this fact, even if they have not dropped comparative advantage theory. As one session paper put it: “the distributional effects of financial globalization, unlike those of trade, have gone largely unrecognized. In fact, however, episodes of capital account liberalization are followed by an increase in the gini coefficient and top income shares and declines in the labor share of income. These distributional effects hold with a de jure measure of liberalization and only get stronger when this measure is scaled by the extent of the capital flows that ensue in the aftermath of liberalization. Financial globalization emerges as a robust determinant of inequality, even after accounting for the effects of trade, technology and other drivers.” (Jeffry Frieden, Harvard University).

MakingFinancialGlobalizationMoreIncl_preview

Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the gurus of inequality, showed in their session, that inequality of income and wealth rose sharply during the neoliberal period of globalisation and free trade. They presented new evidence that global inequality and growth since 1980 has increased almost everywhere, if at very different speeds. Growth in incomes has been explosive for the global top income earners. TheElephantCurveOfGlobalInequality_powerpoint

But what really worries the mainstream in their defence of the capitalist mode of production are the consequences of the end of globalisation and the potential reversal of free trade – namely the rise of ‘populism’ in the major capitalist economies. In Europe, anti-free trade, anti-immigrant nationalist parties are polling 25-30% in elections, threatening the status quo of the pro-capitalist centre right and social democratic parties. In the US, there is Trump and his 30%-plus support and in the UK, there is Brexit. Neoliberalism threatens to be replaced by nationalist reaction, leading to the end of ‘democracy’ (i.e. the existing capitalist order of ‘business as usual’). This is the fear of Rodrik and Stiglitz and the other gurus at ASSA. MakingGlobalizationMoreInclusiveWhe_powerpoint

But it was also expressed in one of the ASSA sessions held by the Union of Radical Political Economy (URPE). In the David Gordon memorial lecture, longstanding Marxist economist John Weeks talked of “authoritarian tendencies” having a “quantum leap” both in Europe because of “austerity” and in China and Vietnam where central planning has been replaced by “market authoritarianism”.

FreeMarketsAndTheDeclineOfDemocracy_preview

Why has this happened? According to Weeks, it “comes from the excesses generated by capitalist competition, unleashed and justified now not by fascism but by neoliberalism.” You see, the rules of trade and competition were altered under neoliberalism to benefit finance and oligopolies at the expense of labour and the rest. “The purpose of destroying the post war regulatory consensus was to liberate financial capital from constraints. The macroeconomics of Keynes and even more so Kalecki influenced provided both the theoretical explanation for why these constraints were needed and the practical policy tools to manage an economy within those constraints. The “Keynesian revolution” briefly institutionalized the sensible principle that representative governments have policy tools they can use to pursue the welfare of the populations they were elected to serve.”

But is the reason for the rise of reactionary semi-fascist nationalism due to ‘the excesses” of neoliberalism, finance capital (but not industrial capital?) and austerity? Or through changing the nice “sensible principles” of government management of the economy that apparently started with the New Deal and continued (“briefly”) with the consensus post-war Keynesian policies?

I don’t think this is a convincing explanation. Keynesian or New Deal policies of fiscal and monetary management of the capitalist economy, in so far as they were ever applied (and that was limited indeed), collapsed in the 1970s and neoliberal policies of financial deregulation, globalisation and the reduction of the welfare state came in. But that was not because politicians decided to ‘change the rules’ and ‘rational’ Keynesian policies were dispensed with for the greed of the 1%.

This is the argument of the mainstream liberal economists like Joseph Stiglitz who wrote a book exactly along those lines. But it was not a change of ideology alone – it was the result of forced circumstances for capitalism from the late 1960s onwards. The capitalist mode of production got into deep trouble as the profitability of capital plunged everywhere. A drastic reversal of economic policy was necessary. Out went the Keynesian ‘revolution’; in came monetarism, Hayekian free markets, the crushing of unions and the ending of trade barriers and government intervention.

This worked for capitalism for a whole generation and profitability recovered (at least somewhat) at the expense of labour, mainly through a rising rate of exploitation (as well as globalisation). But, as Marx’s law of profitability argues, the counteracting factors to the tendency for profitability of capital to decline over time do not work forever. The global financial crash, the ensuing Great Recession and the subsequent Long Depression confirmed that the era of globalisation and neoliberal policies were no longer working. And now the consensus among mainstream economics is broken. Rethinking economics is now the cry.

It was not the ‘excesses’ of neoliberalism and globalisation that caused the rise of nationalism and Trump, but the failure of the capitalist mode of production to deliver. The likes of Stiglitz, Phelps, DeLong, Krugman etc want to ‘change the rules’ back so that capitalism can be ‘managed’. But this is an illusory aim unless the profitability of capital returns on a sustained basis.

In his address, Marxist John Weeks naturally went further than the mainstream Joseph Stiglitz in his policies for change. But, in my view, it won’t be enough just to “reform” markets “to prevent the power of financial capital from creating fascism for the 21st century and so rebuild “social democracy for the 21st century”. The capitalist mode of production must be completely replaced, if labour is to benefit and future crises are to be avoided. And that means a global planned economy to mobilise resources, innovation and labour skills, let alone to end global warming and climate change.

In part 2 of ASSA 2018, I’ll discuss the papers presented in sessions of the radical economists attending.

No comments:

Post a Comment