At ASSA 2018, away from the huge arenas where thousands listened to the millionaire guru mainstream economists speak, were the sessions under the umbrella of the Union of Radical Political Economics (URPE), where just handfuls heard papers from a range of heterodox and radical economists. These sessions were a mixture of debate on Marx’s value theory (among Marxists) and its dismissal by followers of Piero Sraffa. But there was also some very interesting research on the nature of capitalist economic cycles and the causes of crises, including the 2008 crash and the Great Recession.

Supporters of ‘neo-Ricardian’ theorist, Piero Sraffa, had a session aimed at comparing Marx’s analysis of capitalism with their own hero. In his ‘point by point’ comparison of Marx and Sraffa, Robin Hahnel explained that Marx was the “great grandfather” of the critique of capitalism, but “a great deal has happened since Marx died in 1883”and it was time to acknowledge that “Marx’s attempt to fashion a formal economic theory of price and income determination in capitalism based on a labor theory of value, and elaborate a Hegelian critique of capitalism, can now be surpassed”. Now “a number of distinguished Sraffian economists have used modern mathematical tools to elaborate an intellectually rigorous version of Sraffian theory which surpasses formal Marxian economic theory in every regard”.

APointByPointComparisonOfSraffian_powerpoint

To justify this claim, Harnel then offers the usual set of neo-Ricardian arguments against Marx’s value theory (first raised by Ian Steedman in 1977): values are not necessary to explain prices or profit under capitalism, indeed they are redundant; Marx’s value and profitability theories are empirically refuted; and anyway, Okishio has completely rebutted Marx’s theory of crises based on the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

There is no room in this post to respond properly to these traditional arguments of the Sraffians. Instead I refer readers to the battery of work done by Marxist economists over the last 40 years that show the logic of Marx’s theory, expose the unrealistic assumptions in Sraffa’s approach and provide empirical support for Marx’s laws of motion under capitalism. I have only to mention but a few: the work of Husson, Carchedi, Freeman, Kliman and Moseley among many others.

Indeed, at ASSA, in other sessions Marxist value theory was convincingly expounded. Riccardo Bellofiore took us carefully on a tour through Marx’s value theory from various angles. And see Bellofiore’s account of Sraffa from another session.

KarlMarxsCritiqueOfPoliticalE_preview

ContemporaryStagnationAndMarxismSwe_preview

And Fred Moseley recounted his important summary of Marx’s value theory and laws of motion in his book of last year, Money and Totality. His book offers a firm critique of Sraffian theory as well as a convincing interpretation of the so-called transformation problem of ‘converting’ labour values into the prices of production – an issue that the Sraffians and all critics of Marx’s value theory latch onto.

MoneyAndTotalityAMacromonetaryInt_preview

At ASSA, Moseley’s ‘macro-monetary’ approach to Marx’s value theory was criticised by David Laibman and Gilbert Skillman.

TotalityTautologyAndTransformation_preview

But Moseley was firm in his view that “Marx’s theory of capitalism is internally logically consistent. The long-standing and widely-held criticism that Marx “failed to transform the inputs” in his theory of prices of production in Volume 3 is not a valid criticism. Marx did not fail to transform the inputs because the inputs are not supposed to be transformed. The inputs of constant capital and variable capital are the same actual quantities money capital advanced at the beginning of the circuit of money capital to purchase means of production and labor-power which are taken as given”. So prices of production can be derived from total surplus-value and general rate of profit in a logically consistent way. Marx’s value theory is both necessary and sufficient in explaining market prices, indeed better than mainstream neoclassical marginalist theory or the ‘physicalist’ production equations of Sraffa.

As I said, the debate between Marxists and the neo-Ricardians/Sraffians is now over 40 years old. It boils down to whether you think Marx’s value theory and his critique of capitalism is logically valid. Marxists have, in my opinion, conclusively won that debate.

But for Marxist economics in the last 15 years, and certainly since the Great Recession, the issue has moved on to whether Marx’s value and crisis theory is empirically supported. There has been a mountain of studies on this – with work by Freeman, Kliman, Moseley, Carchedi (and myself). And this year, Carchedi and I will publish a collection of research by young Marxist economists from all corners of the globe that help verify empirically Marx’s law of profitability and theory of crises.

And at ASSA, yet more convincing empirical work was presented. In particular, David Brennan presented an analysis based, he said, on using Marx’s law of profitability and Michal Kalecki’s macro identities. Brennan offered “a new methodology based on the work of Kalecki to provide empirical estimates of profits and the various components of realization, profit rates, and the organic composition of capital. These estimates provide new insights into the Great Recession and the “recovery.”

RegimesOfRealizationUsingMarxAndK_preview

Now readers of this blog and some of my research papers will know that I have serious criticisms of the Keynes/Kalecki macro identities as a useful tool in explaining crises under capitalism. In essence, as Brennan also shows when he goes through the macro categories, the capitalist economy’s driver can be boiled down to profits=investment identity.

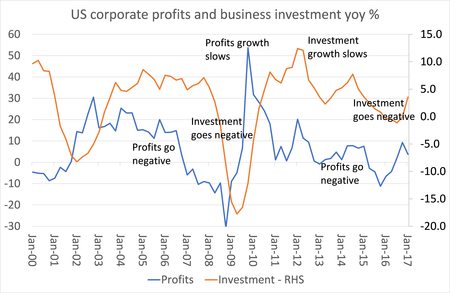

Why? Because if we assume workers in general consume all they get and capitalists save all they get, while governments balance their books and external trade is in balance, then all that is left is profits=investment. The Keynesian/Kalecki conclusion is that investment drives or creates profits based on the view of the ‘effective demand’ of capitalists. But this is back to front. The Marxist view is that profits drive or create investment, not vice versa. And there is plenty of empirical evidence to confirm the Marxist view.

But Brennan wanted to make the point that crises could not be caused by just a fall in the rate of profit; slumps also depend on the realisation of the mass of profit. “Marxian theory was not wrong about the causes of the Great Recession, although various Marxian theories emphasized different aspects of the crisis. In the end, the rate of profit matters for the trajectory of the economy. But to understand crises like the Great Recession, profit rates alone are not sufficient. Crises, unlike typical recessions, are sudden and often unforeseen. The Great Recession was both a profit rate and a profit realization crisis.”

Brennan sees the latter as the contribution of Kalecki. Actually, Marx’s theory of crises has always taken that into account. Indeed, when the rate of profit falls and is no longer compensated for by a rise in the mass of profit, a slump is set to come. The Marxist economist, Henryk Grossman, particularly emphasised this aspect of Marx’s crisis theory.

As Marx put it: “the so-called plethora (overaccumulation) of capital always applies to a plethora of capital for which the fall in the rate of profit is not compensated by the mass of profit… and “overproduction of commodities is simply overaccumulation of capital”. It is precisely when the mass of profit stopped rising that the Great Recession ensued.

And this is what Brennan finds in the US data using his combination of a Marxian rate of profit and ‘Kalecki’ profits. The profit rate fell in the 1964-1980 period and then rose in the neoliberal 1980-2006 period, fell during the Great Recession and recovered subsequently. These results repeat what a host of studies have already shown.

Brennan now adds the impact of the movement in the mass of profits (a la Kalecki) and finds that the Marxian profit rate peaked well before the global financial crash and then was followed a fall in the mass of profit and investment. “It was the significant dip in total profit flows coupled with the low rates of profit, accumulation and exploitation that formed the Great Recession.” Exactly: below is my version.

Brennan adds a slightly different interpretation: “The rate of exploitation up to that time peaked during 2006Q1. Yet profit flows continued to rise until 2008Q3. Therefore, the financial sector was essentially trying to realize profit gains that were not there in real production. This is one reason why the housing boom could not continue much past the end of 2005. While the crisis was indeed precipitated by the housing collapse, the collapse was brought on by difficulties of both profit production and realization.” Yet, Brennan’s Kalecki analysis confirms the Marxist analysis already presented by Carchedi, Freeman, Kliman, (myself) and many others.

Marx’s crisis theory stands out as mainstream economics flails about, unable to forecast or explain the global financial crash, the ensuing Great Recession and the Long Depression that has followed.

No comments:

Post a Comment