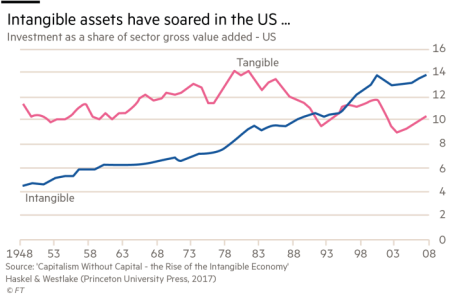

There is a new book out called Capitalism without capital – the rise of the intangible economy. The authors, Jonathan Haskel of Imperial College and Stian Westlake of Nesta, are out to emphasise a big change in the nature of modern capital accumulation – namely that increasingly investment by large and small companies is not in what are called tangible assets, machines, factories, offices etc but in ‘intangibles’, research and development, software, databases, branding and design. This is where investment is rising fast relative to investment in material items.

The authors call this capitalism without capital. But of course, this is using ‘capital’ in its physicalist sense, not as a mode of production and social relation, as Marxist theory uses the word. For Marxist theory what matters is the exploitive relation between the owners of the means of production (tangible and intangible) and the producers of value, whether they are manual or ‘mental’ workers.

As G Carchedi has explained, there is no fundamental distinction between manual and mental labour in explaining exploitation under capitalism. Capitalism cannot be without capital in that sense.

Knowledge is produced by mental labour but this is not ultimately different from manual labour. Both entail expenditure of human energy. The human brain, we are told, consumes 20% of all the energy we derive from nourishment and the development of knowledge in the brain produces material changes in the nervous system and synaptic changes which can be measured. Once the material nature of knowledge is established, the material nature of mental work follows. Productive labour (whether manual or mental) transforms existing use-values into new use-values (realised in exchange value). Mental labour is labour transforming mental use values into new mental use values. Manual labour consists of objective transformations of the world outside us; mental labour of transformations of our perception and knowledge of that world. But both are material.

The point is that discoveries, generally now made by teams of mental workers, are appropriated by capital and controlled by patents, by intellectual property or similar means. Production of knowledge is directed towards profit. Medical research, for example, is directed towards developing medicines to treat disease, not preventing disease, agricultural research is directed to developing plant types which capital can own and control, rather than relieving starvation.

What Haskell and Westlake find is that investment in intangible assets now exceeds that in tangible assets.

And they reckon this is changing the nature of modern capitalism. Indeed, it could expose the uselessness of the so-called market economy. The argument is that an intangible asset (like a piece of software) can be used over and over again at low cost and allow a business to grow very fast. That’s an exaggeration, of course, because tangible assets like machines can also be used over again, but it’s true that they have ‘wear and tear’ and depreciation. But then software also gets out of date and also becomes ‘tired’ for the continually changing purposes required.

Indeed, the ‘moral depreciation’ of intangibles is probably even greater than tangibles and so increases the contradictions of capitalist accumulation. For an individual capitalist, protecting profit gained from a new piece of research or software, or the branding of a company, becomes much more difficult when software can easily be replicated and brands copied.

Brett Christophers showed in his book, The Great Leveller, capitalism is continually facing a dynamic tension between the underlying forces of competition and monopoly. “Monopoly produces competition, competition produces monopoly” (Marx).

That’s why companies are keen on intellectual property rights (IPR). But IPR is actually inefficient in developing production. ‘Spillover’, as the authors call it, where the benefit of any new discovery is shared in the community, is more productive, but by definition almost, is only possible outside capitalism and private profit – in other words rather than capitalism without capital; it becomes capital without capitalism.

As Martin Wolf of the FT concludes in his analysis of the rise of ‘intangibles’, “intangibles exhibit synergies. This goes against the spillovers. Synergies encourage inter-firm co-operation (or outright mergers), while spillovers are likely to discourage it. Who really wants to give a free lunch to competitors?” So “Taken together, these features explain two other core features of the intangible economy: uncertainty and contestedness. The market economy ceases to function in the familiar ways.”

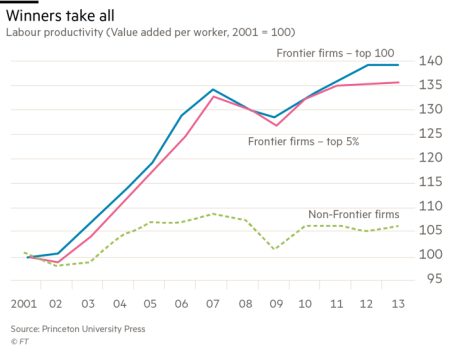

Under capitalism, the rise of intangible investment is leading to increased inequality between capitalists. The leading companies are controlling the development of ideas, research and design and blocking ‘spillover’ to others. The FANGs are gaining monopoly rents as a result, but at the expense of the profitability of others, reducing them to zombie status (just covering their debts without the ability to expand or invest).

Indeed, the control of intangibles by a small number of mega companies could well be weakening the ability to find new ideas and develop them. Research productivity is declining at a rate of about 6.8 per cent per year in the semiconductor industry. In other words, we’re running out of ideas. That’s the conclusion of economic researchers from Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Innovation. They reckon that in order to maintain Moore’s Law – by which transistor density doubles every two years or so – it now takes 18 times as many scientists as it did in the 1970s. That means each researcher’s output today is 18 times less effective in terms of generating economic value than it was several decades ago.

Thus we have the position where the new leading sectors are increasingly investing in intangibles while investment overall falls along with productivity and profitability. Marx’s law of profitability is not modified but intensified.

The rise of intangibles means the increased concentration and centralisation of capital. Capital without capitalism becomes a socialist imperative.

No comments:

Post a Comment