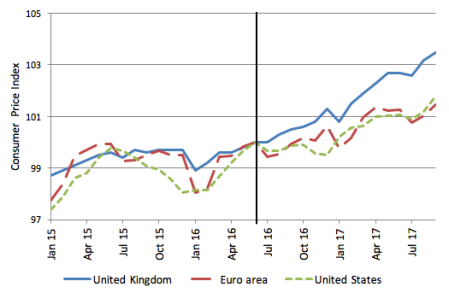

And then there is Brexit. The cabinet is split between the so-called hard Brexiters (supporters of leaving the EU) and the ‘Remainers’ in negotiating with the EU. As a result, nothing has been achieved for over a year in the negotiations for a new arrangement with the EU. In the meantime, the pound sterling has slumped and inflation has spiralled.

Even before Brexit, the UK economy, was already showing serious signs of frailty. In a previous post, I showed: the underlying feebleness of output growth (the slowest growing G7 economy); productivity among the lowest among advanced economies (and not rising); and investment to GDP that has been falling for over 30 years. This failure of capitalist production in the UK has meant that the average British household has experienced no ‘recovery’ at all income since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. Real wage growth is at its slowest since the mid-19th century. Indeed, the UK is one (and the largest) of six countries in the 30-country OECD bloc where earnings are still below their 2007 levels (the UK is joined by Greece and Portugal).

In his budget speech, Hammond made two ridiculous claims. The first was that it was “Labour’s Great Recession”. The only correct bit in this statement was that there was terrible slump in 2008-9 globally that hit the UK too when a Labour government was in office. But it was not Labour’s recession but that of global capitalism. The financial crash, the slump in production and rise in unemployment, along with a rocketing budget deficit and debt was a failure of capitalism under which Labour was helpless.

The other ludicrous claim from Hammond was that income inequality in Britain was improving under the Conservatives and was now at its most equal in 30 years. This claim is based on the gini coefficient of income inequality. This indeed has fallen slightly since 1987 after reaching an all-time high under the Thatcher government. But the main part of that fall was after the Great Recession when incomes for the rich (from financial assets and property) took a bit of hit.

The slight improvement in the inequality ratio from an all-time high did not come from any government action on taxes or benefits at all. So Hammond can hardly claim the credit, especially as Labour governments were in office for nearly half that time. Hammond pointed out that top 1% of income earners are paying more income tax than ever before. But then they have never earned so much! The richest 20% of Brits still have around five times more to spend after taxes and benefits than the poorest 20%.

And as for the ‘economic recovery’ under the Conservatives since 2010, it has been very poor. The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) points out that national income per adult was 15% lower at the last Budget in March than it would have been if pre-2008 trends had continued. By 2022, the gap is set to grow to 18%, performance the IFS describes as “astonishing”. The UK economy is currently growing at its slowest since the end of the Great Recession. And the official forecast for real GDP growth has been revised down to 1.5% for this year and 1.4% in 2018. Indeed, the long-term forecast (and that assumes no slump) out to 2022 is just 1.4% a year, down from a previous forecast of 1.9% a year. Real GDP is now expected to grow by 5.7% between 2017-18 and 2021-22 – down from 7.5% forecast last March.

The main reason is that official forecast for productivity growth has been reduced after successive optimistic forecasts proved wrong. Even so, the productivity forecast for the next five years remains well above the current rate (which is virtually static). And even that means a per capita growth rate of under 1% a year until 2023, or half the long-term average.

As a result, the Conservatives great aim to reduce the annual budget deficit to zero has been pushed out yet again to 2023 and beyond, some 20 years after the Great Recession drove it up to 10% of GDP. And the public sector net debt ratio to GDP, which more than doubled during the recession will only peak this year (if Hammond is right) at about 86.5% of GDP (closer to 100% on a gross basis). And it will fall back only a little to 79% by 2023 – still double its pre-crisis level in 2006.

Moreover, the government’s debt forecast includes £15bn from the sale of the taxpayer’s stake in the Royal Bank of Scotland (at a loss, as the current share price is 271p compared to the break-even price of 502p) – and by moving local housing association debt off the books. So the small debt reduction is achieved by selling off public assets at a loss and by changing the accounting rules.

And even that improvement will require yet more measures of ‘austerity’, ie cuts in government spending and services. Austerity will continue into the next decade if this government has its way. Analysis by the IFS finds that existing plans mean welfare, the health service and prisons face further deep cuts, regardless of the budget, leaving departments such as justice and work and pensions facing a real-terms cut of as much as 40% over the decade to 2020. There will be a further £12bn cut in welfare spending by 2020/21, that the NHS will face its tightest funding period since the 1950s and that prisons will see a real-terms cut of 22%.

Hammond announced some extra funding of the National Health Service, mainly to get it through a major crisis this winter as the old and infirm struggle. But the extra spending of about £3bn over two years is little more than the spending on Brexit planning. Without Brexit, the government could have doubled its funding. And the NHS will still be badly underfunded and, according to the IFS, “If anything, it looks like the funding increases over the next few years get a bit harder rather than a bit easier”. For example, the NHS budget increased by 8.6% a year between 2001/2 and 2004/5, but increases will average just 1.1% a year from 2009/10 to 2020/21. Public funding for health care as a proportion of GDP is now forecast to fall from 7.6% in 2009/10 to 6.8% by 2019/20. Growth in health spending will not keep pace with the growing and ageing population, so NHS spending per person will fall by 0.3% next year.

Hammond announced the removal of taxes on buying a home under £300k, supposedly to help first-time buyers. But it is the law of unintended consequences here – this will just drive prices up even more.

Overall, Hammond’s budget injects about 0.4% of GDP into the economy, mainly through government spending on R&D, infrastructure and housing incentives. That is nowhere near compensating for the downward revisions in the prospects for economic growth as business investment and productivity stagnate.

Britain has been a rentier economy extraordinaire, with the highest dependence on the financial sector of all major economies. And the biggest fall in productivity growth has been in this sector since 2007.

Moreover, with Brexit, the City of London is set to lose many facilities and expertise to Europe. And another recession is due before the end of this decade. Even the reduced growth forecasts look optimistic.

No comments:

Post a Comment