During the current Chinese Communist party congress, Zhou Xiaochuan, governor of the People’s Bank of China, commented on the state of the Chinese economy. “When there are too many pro-cyclical factors in an economy, cyclical fluctuations will be amplified…If we are too optimistic when things go smoothly, tensions build up, which could lead to a sharp correction, what we call a ‘Minsky Moment’. That’s what we should particularly defend against.”

Here Zhou was referring to the idea of Hyman Minsky, the left Keynesian economist of the 1980s, who once put it: “Stability leads to instability. The more stable things become and the longer things are stable, the more unstable they will be when the crisis hits.” China’s central banker was referring to the huge rise in debt in China, particularly in the corporate sector. As a follower of Keynesian Minsky, he thinks that too much debt will cause a financial crash and an economic slump.

Now readers of this blog will know that I do not consider a Minsky moment as the ultimate or main cause of crises – and that includes the global financial crash of 2008 that was followed by the Great Recession, which many have argued was a Minsky moment.

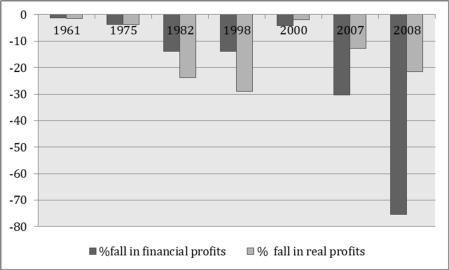

Indeed, as G Carchedi has shown in a new paper recently presented to the Capital.150 conference in London, when both financial profits and profits in the productive sector start to fall, an economic slump ensues. That’s the evidence of post-war slumps in the US. But a financial crisis on its own (falling financial profits) does not lead to a slump if productive sector profits are still rising.

Nevertheless, a financial sector crash in some form (stock market, banks, or property) is usually the trigger for crises, if not the underlying cause. So the level of debt and the ability to service it and meet obligations in the circuit of credit does matter.

That brings me to the evidence of the latest IMF report on Global Financial Stability. It makes sober reasoning.

The world economy has showed signs of a mild recovery in the last year, led by an ever-rising value of financial assets, with new stock price highs. President Trump plans to cut corporate taxes in the US; the Eurozone economies are moving out of slump conditions, Japan is also making a modest upturn and China is still motoring on. So all seems well, comparatively at least. The Long Depression may be over.

However, the IMF report discerns some serious frailties in this rose-tinted view of the world economy. The huge expansion of credit, fuelled by major central banks ‘printing’ money, has led to a financial asset bubble that could burst within the next few years, derailing the global recovery. As the IMF puts it: “Investors’ concern about debt sustainability could eventually materialize and prompt a reappraisal of risks. In such a downside scenario, a shock to individual credit and financial markets …..could stall and reverse the normalization of monetary policies and put growth at risk.”

What first concerns the IMF economists is that the financial boom has led to even greater concentration of financial assets in just a few ‘systemic banks’. Just 30 banks hold more than $47 trillion in assets and more than one-third of the total assets and loans of thousands of banks globally. And they comprise 70 percent or more of international credit markets. The global credit crunch and financial crash was the worst ever because toxic debt was concentrated in just a few top banks. Now ten years later, the concentration is even greater.

Then there is the huge bubble that central banks have created over the last ten years through their ‘unconventional’ monetary policies (quantitative easing, negative interest rates and huge purchases of financial assets like government and corporate bonds and even corporate shares). The major central banks increased their holdings of government securities to 37 percent of GDP, up from 10 percent before the global financial crisis. About $260 billion in portfolio inflows into emerging economies since 2010 can be attributed to the push of unconventional policies by the Federal Reserve alone. Interest rates have fallen and the banks and other institutions have been desperately looking for higher return on their assets by investing globally in stocks, bonds, property and even bitcoins.

But now the central banks are ending their purchase programmes and trying to raise interest rates.

This poses a risk to the world economy, fuelled on cheap credit up to now. As the IMF puts it: “Too quick an adjustment could cause unwanted turbulence in financial markets and international spillovers … Managing the gradual normalization of monetary policies presents a delicate balancing act. The pace of normalization cannot be too fast or it will remove needed support for sustained recovery”. The IMF reckons portfolio flows to the emerging economies will fall by $35bn a year and “a rapid increase in investor risk aversion would have a more severe impact on portfolio inflows and prove more challenging, particularly for countries with greater dependence on external financing.”

What worries the IMF is that this this borrowing has been accompanied by an underlying deterioration in debt burdens. So “Low-income countries would be most at risk if adverse external conditions coincided with spikes in their external refinancing needs.”

But it is what might happen in the advanced capital economies on debt that is more dangerous, in my view. As the IMF puts it: “Low yields, compressed spreads, abundant financing, and the relatively high cost of equity capital have encouraged a build-up of financial balance sheet leverage as corporations have bought back their equity and raised debt levels.” Many companies with poor profitability have been able to borrow at cheap rates. As a result, the estimated default risk for high-yield and emerging market bonds has remained elevated.

The IMF points out that debt in the nonfinancial sector (households, corporations and governments) has increased significantly since 2006 in many G20 economies. So far from the global credit crunch and financial crash leading to a reduction in debt (or fictitious capital as Marx called it), easy financing conditions have led to even more borrowing by households and companies, while government debt has risen to fund the previous burst bubble.

The IMF comments “Private sector debt service burdens have increased in several major economies as leverage has risen, despite declining borrowing costs. Debt servicing pressure could mount further if leverage continues to grow and could lead to greater credit risk in the financial system.”

Among G20 economies, total nonfinancial sector debt has risen to more than $135 trillion, or about 235 percent of aggregate GDP.

In G20 advanced economies, the debt-to-GDP ratio has grown steadily over the past decade and now amounts to more than 260 percent of GDP. In G20 emerging market economies, leverage growth has accelerated in recent years. This was driven largely by a huge increase in Chinese debt since 2007, though debt-to-GDP levels also increased in other G20 emerging market economies.

Overall, about 80 percent of the $60 trillion increase in G20 nonfinancial sector debt since 2006 has been in the sovereign and nonfinancial corporate sectors. Much of this increase has been in China (largely in nonfinancial companies) and the United States (mostly from the rise in general government debt). Each country accounts for about one-third of the G20’s increase. Average debt-to-GDP ratios across G20 economies have increased in all three parts of the nonfinancial sector.

The IMF comments: “While debt accumulation is not necessarily a problem, one lesson from the global financial crisis is that excessive debt that creates debt servicing problems can lead to financial strains. Another lesson is that gross liabilities matter. In a period of stress, it is unlikely that the whole stock of financial assets can be sold at current market values— and some assets may be unsellable in illiquid conditions.”

And even though there some large corporations that are flush with cash, the IMF warns: “Although cash holdings may be netted from gross debt at an individual company—because that firm has the option to pay back debt from its stock of cash—it could be misleading”. This is because the distribution of debt and cash holdings differs between companies and those with higher debt also tend to have lower cash holdings and vice versa.

So “if there are adverse shocks, a feedback loop could develop, which would tighten financial conditions and increase the probability of default, as happened during the global financial crisis.”

Although lower interest rates have helped lower sovereign borrowing costs, in most of the G20 economies where companies and households increased leverage, nonfinancial private sector debt service ratios also increased. And there are now several economies where debt service ratios for the private nonfinancial sectors are higher than average and where debt levels are also high. Moreover, a build-up in leverage associated with a run-up in house price valuations can develop to a point that they create strains in the nonfinancial sector that, in the event of a sharp fall in asset prices, can spill over into the wider economy.

The IMF sums up the risk. “A continuing build-up in debt loads and overstretched asset valuations could have global economic repercussions. … a repricing of risks could lead to a rise in credit spreads and a fall in capital market and housing prices, derailing the economic recovery and undermining financial stability.”

Yes, banks are in better shape than in 2007, but they are still at risk. Yes, central banks are ready to reduce interest rates if necessary, but as they are near zero anyway, there is little “scope for monetary stimulus. Indeed, monetary policy normalization would be stalled in its tracks and reversed in some cases.”

The IMF poses a nasty scenario for the world economy in 2020. The current ‘boom’ phase can carry on. Equity and housing prices continue to climb in overheated markets. This leads to investors to drift beyond their traditional risk limits as the search for yield intensifies despite increases in policy rates by central banks.

Then there is a Minsky moment. There is a bust, with declines of up to 15 and 9 percent in stock market and house prices, respectively, starting at the beginning of 2020. Interest rates rise and debt servicing pressures are revealed as high debt-to-income ratios make borrowers more vulnerable to shocks. “Underlying vulnerabilities are exposed and the global recovery is interrupted.”

The IMF estimates that the global economy could have a slump equivalent to about one-third as severe as the global financial crisis of 2008-9 with global output falling by 1.7 percent from 2020 to 2022, relative to trend growth. Capital flows to emerging economies will plunge by about $65 billion in one year.

Of course, this is not the IMF’s ‘base case’; it is only a risk. But it is a risk that has increasing validity as stock and bond markets rocket, driven by cheap money and speculation. If we follow the Carchedi thesis, the driver of the bust would be when profits in the productive sectors of the economy fall. If they were to turn down along with financial profits, that would make it difficult for many companies to service the burgeoning debts, especially if central banks were pushing up interest rates at the same time. Any such downturn would hit emerging economies severely as capital flows dry up. The Carchedi crunch briefly appeared in the US in early 2016, but recovered after.

Zhou is probably wrong about China having a Minsky moment, but the advanced capitalist economies may have a Carchedi crunch in 2020, if the IMF report is on the button.

No comments:

Post a Comment