It’s an historic day in global central bank monetary policy since the end of the Great Recession. The US Federal Reserve Bank feels sufficiently confident about the state of the US economy and, for that matter the rest of the major economies, to announce that it has not only ended quantitative easing (QE) but that it is now going to reverse the process into quantitative tightening.

QE was the policy of pumping money (by creating bank reserves) into the financial sector by buying government and corporate bonds (and even shares) in order to create enough cash in the banks to lend onto households and companies and keep interest rates (the cost of borrowing) to near zero (or even below in some countries). QE was the key monetary policy of the financial authorities in the major economies, particularly in the light of little fiscal or government spending as a second or alternative weapon. Fiscal austerity was applied (with varying degrees of success) while monetary policy was ‘eased’.

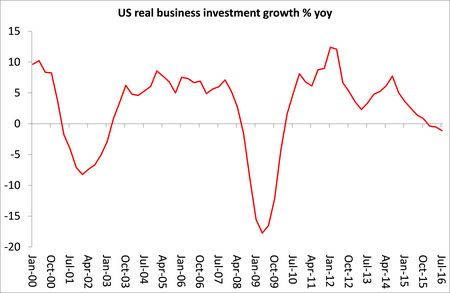

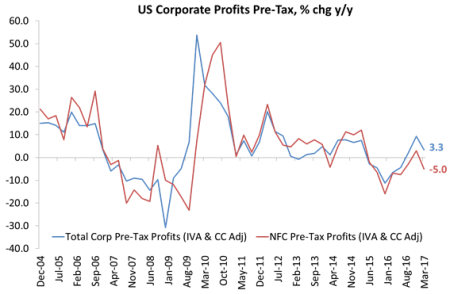

But QE was really a failure. It did not lead to a revival of economic growth or business investment. Growth of GDP per head and investment in the major economies continue to languish well below pre-crisis rates. As I have argued in this blog, that is because profitability in capitalist sector remains below pre-crisis levels and well below the peaks of the late 1990s.

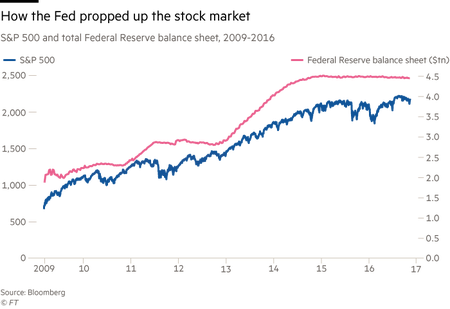

What QE did do was fuel a new speculative bubble in financial assets, with stock and bond markets hitting ever new heights. As a result, the very rich who own most of these assets became much richer (and inequality of income and wealth has risen even further). And the very large companies, the FANG (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google) in the US, became flush with cash and doubled-up on borrowing even more at near zero rates so that they could buy up their own shares and drive up the stock price, hand out big dividends to shareholders and use funds to buy up even more companies.

But now eight years after QE was launched in the US, followed by the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England and eventually the European Central Bank, the US Fed is preparing to reverse the policy. It has announced that it will start selling off its huge stock of bonds ($4.5trn or 25% of US GDP at the last count) over the next few years. The sell-off will be gradual and the Fed is cautious about the impact on the financial sector and the wider economy. And it should be.

Financial markets won’t like it. The drug of cheap (virtually interest-free) money is being slowly withdrawn. The plan is to avoid ‘cold turkey’, but even so the stock and bond markets are likely to sell off as the supply of free money begins to fall back. More important is what will happen to the productive sectors of the US economy and, for that matter, to the global economy, as this cheap money slowly declines.

The Fed sounds confident. As Janet Yellen, the head of the Fed put it in the press conference yesterday: “The basic message here is US economic performance has been good; the labour market has strengthened substantially. The American people should feel the steps we have taken to normalise monetary policy are ones we feel are well justified given the very substantial progress we have seen in the economy.”

This confidence is being increasingly backed up by the mainstream economic forecasters. For example, Gavyn Davies, former chief economist at Goldman Sachs and now columnist at the FT, reports that his Fulcrum ‘nowcast’ activity measures reveals the “growth rate in the world economy is being maintained at the firmest rate recorded since the early days of the recovery in 2010. The growth rate throughout 2017 has been well above trend for both the advanced and emerging economies, and the acceleration has been more synchronised among the major blocs than at any time since before the Great Financial Crash.” He has the advanced economies growing at 2.7% and the world economy at 4.1%, with the US growth rate now around 3%. This all sounds good.

And yet the long-term forecasts of the Fed policy makers for economic growth and inflation remain low. Indeed, there are some important caveats to this seeming confidence. First, there is little sign of any recovery in business investment.

Second, far from profits in the productive sectors racing ahead, overall non-financial corporate profits in the US are falling.

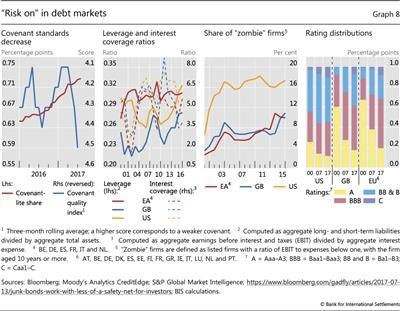

And equally important, as the recent Bank for International Settlements quarterly review has highlighted, corporate debt is very high and rising, while the number of ‘zombie’ companies (those hardly able to meet their debt payments) are at record levels (16% in the US). At $8.6 trillion, US corporate debt levels are 30% higher today than at their prior peak in September 2008. At 45.3%, the ratio of corporate debt to GDP is at historic highs, having recently surpassed levels preceding the last two recessions. That suggests that increased costs of debt servicing from rising interest rates driven by the Fed’s ‘normalisation’ policy could tip things over, unless profitability recovers for the wider corporate sector.

As the BIS summed it up, “Even accounting for the large cash balances outstanding, leverage conditions in the United States are the highest since the beginning of the millennium and similar to those of the early 1990s, when corporate debt ratios reflected the legacy of the leveraged buyout boom of the late 1980s. Taken together, this suggests that, in the event of a slowdown or an upward adjustment in interest rates, high debt service payments and default risk could pose challenges to corporates, and thereby create headwinds for GDP growth.”

And this is just at a time when the US Fed has decided to hike its short-term policy interest rate and cut back on the lifeline of cheap money to the banks. As I have pointed out before, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Fed did something similar in 1937, reversing its policy of cheap credit when it thought the depression was over. That led to a new slump in production in 1938 that only the second world war ended. The risk of repeat remains.

No comments:

Post a Comment