The news that Brazil’s right-wing President Temer has been caught trying to bribe politicians to keep quiet about corruption allegations increases the likelihood that he will be impeached by Brazil’s Congress this year. Temer is already the most unpopular president in Brazil’s democratic history. He only got into office by organising a ‘constitutional coup’ that ousted elected centre-left President Dilma Rousseff on the grounds of so-called ‘budgetary violations’. An alliance of parties in favour of pro-capitalist measures to cut wages, social benefits and pensions took over Congress to back Temer. Brazil’s stock markets and currency boomed and international capital returned to invest.

But now all these ‘reforms’ in the interests of profitability are in jeopardy. Even though the neo-liberal policies adopted by the previous Workers Party presidents Lula and Dilma led to a loss of support among Brazil’s working class and their eventual demise, the Temer-led alliance has never commanded majority support and the latest scandal could see its end.

Where this will leave Brazilian economy and its people is difficult to judge – I look to my Brazilian readers to explain. But here I can add that the Temer administration’s aim has been clear: to drive up the low profitability of Brazilian industry and capital by reducing the share going to labour; destroying trade union and other opposition trends; and turning to foreign capital for support.

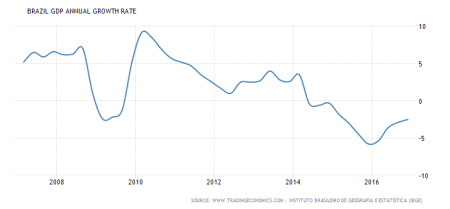

The big reason that the Dilma government fell was the economy. After the collapse of commodity prices from about 2011, Brazil’s economy dived into a delayed but deep slump. And it is still in this economic recession.

But Temer and Brazilian capital, after ousting Dilma, were hoping that a general recovery in the world economy would spread to Brazil. Things would turn around and enable them to cement their rule. And there have been some signs of such a recovery. Brazilian business has shown signs of more confidence.

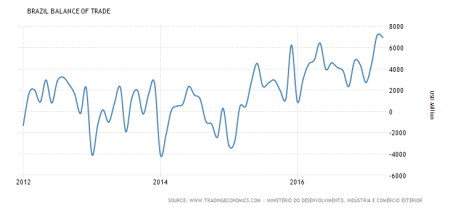

Although commodity prices have not returned to the heady heights of before 2010, they have at least reversed a little from their deep collapse in the period up to the end of 2015. Moreover, in the last year, it seems that the prognosis of a collapse in China and a slowdown in the US has not materialised. And China and the US are by far Brazil’s biggest export markets.

Also, the economic recession has led to a large drop in imports of foreign goods. So Brazil’s trade balance has improved.

And after significant ‘capital flight’ by rich Brazilians under Dilma, foreign investment has started to return to Brazil, given its pro-capitalist government.

One of the results of the deep depression was sharply falling inflation. So, although wages for the average Brazilian family have stagnated or even fallen, in real terms (after inflation) they have risen, if only to the level of two years ago.

But unemployment continues to spiral as Brazil’s companies cut back on staff and public sector jobs are decimated.

The medium-term future for Brazil’s economy does not look bright, despite the recent optimism of mainstream economists and pro-capitalist politicians in Brazil. It was a commodities boom that fuelled much of Brazil’s GDP growth prior to 2010. The country’s share of global non-oil resource exports rose from 5 percent in 2002 to 9 percent in 2012. Today commodity prices remain high compared with their historic averages, but the exceptional surge in both demand and prices has levelled off.

At the same time, both households and corporations remained burdened with significant debt. Household debt has grown from 20 percent of income in 2005 to 43 percent of income in 2012, and high real interest rates (averaging 145 percent on credit cards) make this a heavy burden for consumers. On the government side, federal expenses increased from 15.7 percent of GDP in 2002 to 18.9 percent in 2013, mainly due to interest payments on debt. As a result, taxes have already climbed from 29 percent of GDP in 1995 to 36 percent in 2013, the highest level among Brazil’s emerging market peers. As a share of GDP, Brazil’s gross public sector debt is less than a third that of Japan, but its debt service costs are almost 15 times as high.

Above all, there is little sign that Brazilian capital can really develop the productive forces of the economy and its people. Resource exports and credit-fuelled consumption have not translated into higher investment or productivity. Between 2000 and 2011, Brazil’s overall investment rate averaged 18 percent of GDP, below that of other developing economies such as Chile (23 percent) or Mexico (25 percent), and much below those of China (42 percent) and India (31 percent).

Brazil’s productivity has been almost stagnant since 2000; today it is just over half the level achieved in Mexico.

According to McKinsey, the global management consultants, more than half of Brazil’s population remain below a monthly income per head of R$560. To cut this level of poverty to under 25% would require productivity four times as fast as the current rate. And there is no prospect of that under capitalism in Brazil. That’s because the profitability of Brazilian capital is low and continues to stay low.

The profitability of Brazil’s dominant capitalist sector had been in secular decline, imposing continual downward pressure on investment and growth. Sure, the overthrow of the military regimes and the rise in commodity prices turned round the fall in profitability for a while. But profitability now is still well below its best years in the early 2000s.

The graph below shows three indexed (1963=100) measures (M= Maito; Mar = Marquetti; P = mine based on Penn World tables and poly = smoothed average).

Even if Temer survives, Brazil’s ruling elite face a difficult task in imposing control over its working class and cutting public spending and wages, and thus attracting significant foreign capital. The ruling elite is more likely to flee with its capital at every sign of difficulty. So Brazil capitalism will be stuck in a low growth, low profitability future with continuing political and economic paralysis. And that is without a new global recession coming over the horizon.

No comments:

Post a Comment