One of the ironies of the Brexit vote by the British people (more exactly, the English and the Welsh as the Scots voted to remain), is that the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, otherwise known as TTIP, has been crippled, possibly killed. It looks as though any potential trade agreement with the US will be ‘parked’ by the EU Commission until Britain’s Article 50 (Brexit) negotiations have been completed. Washington is also being forced to put a hold on TTIP because Britain represents 16% of the EU market. Until Britain’s relationship with the EU is finalised, there is no way to assess the nature and scale of the reduction in the EU’s market, making it impossible to value.

There is now a possibility that the deal will never be concluded.

Anyway, with Article 50 unlikely to be invoked very quickly by the new Conservative government under Theresa May, there would seem to be insufficient time to conclude the negotiations before the end of the year, and many in Brussels now want to focus on obtaining the ‘right Brexit’ terms, pushing TTIP down the list of priorities. And with next year’s elections in France, Germany, and Holland, EU leaders will try to avoid another weapon to be used by ‘populist’ parties who see TTIP as another attempt to impose measures of ‘globalisation’ on nation states..

There has been much coverage about how TTIP, if implemented, will impose serious restrictions on the ability of democratic governments to carry out the wishes of their electorates. TTIP and its baby sister, CETA, a similar trade deal that the EU has negotiated with Canada, enable corporations to sue governments in secret commercial Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) courts. This right of litigation exposes governments to lawsuits for any policy-induced losses suffered by a corporation.

Governments are exposed to corporate action through ISDS courts for up to 20 years. But aside from the issue of democratic governments being blocked and sued under these international trade treaties, there is the question of whether international trade agreements, bilateral or multilateral, are beneficial to labour or to capital. The specifically economic base of such a conception is that has been known since the first sentence of the first chapter of the founding work of scientific economics, Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, that: ‘The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour… have been the effects of the division of labour.’

Mainstream economists are convinced that ‘free trade’ is beneficial to all. As Keynesian Paul Krugman put it: “The great majority of economists would argue that the gains from reducing trade protection still exceed the losses. However, it has become more important than before to make sure that the gains from international trade are widely spread.” How the latter is to be done is not explained. Greg Mankiw, the right of centre mainstream economist who reckons that inequality of income is justified, is more honest: “will trade make everyone better off? Probably not. In practice, compensation for the losers from international trade is rare. Without such compensation, opening up to international trade is a policy that expands the size of the economic pie, while perhaps leaving some participants in the economy with a smaller slice.”

The idea that ‘free trade’ is beneficial to all countries and to all classes is a ‘sacred tenet’ of mainstream economics. In his new book, Capitalism, Anwar Shaikh (Chapter 11), analyses in detail the fallacious proposition that if each country concentrated on producing goods or services where it has a ‘comparative advantage’ over others (so its ‘comparative costs’ were lower), then all would benefit. Trading between countries would balance and wages and employment would be maximised.

Shaikh shows that this is not only demonstrably untrue (countries run huge trade deficits and surpluses for long periods; have recurring currency crises; and workers lose jobs from competition from abroad without getting new ones from more competitive sectors). Shaikh also explains why: namely that it is not comparative advantage or costs that drives trade, but the absolute costs. If Chinese labour costs are much lower than American companies’ labour costs in any market, then China will gain market share, even if America has some so-called ‘comparative advantage’. What really decides is the productivity level and growth in an economy and the cost of labour: “free trade will lead to persistent trade surpluses for countries whose capitals have lower costs and persistent trade deficits for those whose capital has higher costs”. (Shaikh p 514).

In the US, the big losers from the current wave of globalization have been the working-class, as Branko Milanovic of the City University of New York details in his new book, Global Inequality. Jobs will go as more efficient economies take trade share from the less efficient and with open markets (no tariffs and special restriction or quotas).

And of course, in the TTIP and TTP (Trans Pacific) deals, nothing is done to help those who lose employment as a result. For example, the US Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program has a budget of about $664 million, or roughly 0.004 percent of GDP; military and security spending used to preserve imperialist markets for the US costs 4000 times more! Instead, just one dollar of every $25,000 in income generated by the United States goes to help people here who have been hurt by globalization. They don’t receive the cash directly; they just have to hope that the program — which offers retooling, retraining, and relocation, among other services — will aid their transition to new jobs.

In reality, these trade agreements like the TTIP and its pacific twin, TTP (already signed but not confirmed by national governments) are aimed to improve the interest of the multinationals in world markets. The trade discussions are really a battle between the stronger and the weaker capitalist economies over whose companies get the best deal. This is the essence of ‘regional’ deals that have replaced the failed and defunct global deals that the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has tried to achieve over the past 20 years..

In the case of the TTP, the agreement is specifically designed by the US and Japan to squeeze the ability of Chinese companies to build market share in Asia. The real character of the US TPP becomes clear immediately the fundamental economic data for its 12 intended signatory countries is examined. The potential signatories are dominated by the G7 economies of the US, Japan, and Canada. These, together with Australia, constitute 90% of the GDP of potential signatories. Participating developing economies – Mexico, Malaysia, Chile, Vietnam and Peru – make up only 8%.

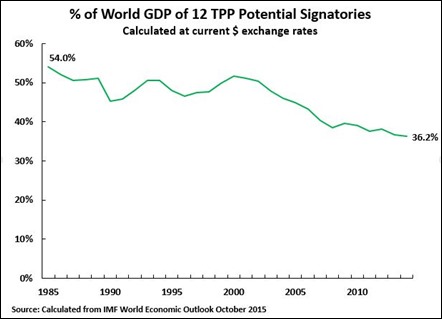

In effect, the TTIP and TTP are really an attempt by the US to stop the decline in global market share at others expense, and also to counteract weakening economic growth and profitability at home. In 1985 economies in the proposed TPP countries accounted for 54% of world GDP; by 2014 this had dropped to 36%. From 1984-2014 the US share of world GDP fell from 34% to 23%, at current exchange rates. In the same period the US share of world merchandise trade dropped from 15% to 11%. So the TPP is not some great free trade beneficence but really an agreement by a group of advanced economies, with a ‘fringe’ of developing countries, whose share in world GDP has been significantly declining to keep others out.

Indeed, it is very far away from the sacred idea of ‘free trade’. As US economist Jeffrey Sachs noted of these TPP provisions: ‘Their common denominator is that they enshrine the power of corporate capital above all other parts of society, including… even governments… The most egregious parts of the agreement are the exorbitant investor powers implicit in the Investor-State Dispute Settlement system as well as the unjustified expansion of copyright and patent coverage. We’ve seen this show before. Corporations are already using ISDS provisions in existing trade and investment agreements to harass governments in order to frustrate regulations and judicial decisions that negatively impact the companies’ interests. The system proposed in the TPP is a dangerous and unnecessary… blow to the judicial systems of all the signatory countries.’

The TPP also gives legal protection to software companies, overwhelmingly US, to essentially spy on signatory states. Article 14.17 states: ‘No Party shall require the transfer of, or access to, source code of software owned by a person of another Party, as a condition for the import, distribution, sale or use of such software, or of products containing such software, in its territory.’ While it is stated this does not apply to ‘critical infrastructure’ it does not exclude banks, commercial companies etc. In short, the conception of the TPP is not to maximise prosperity for the Asia-Pacific Region but to enshrine US supremacy. The TTIP does the same for the US in the European arena.

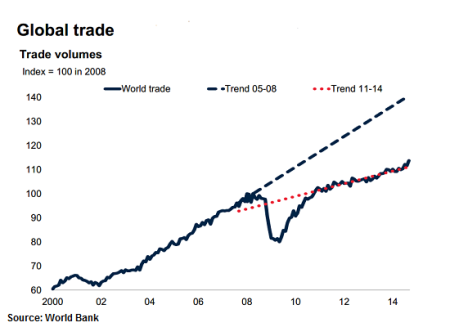

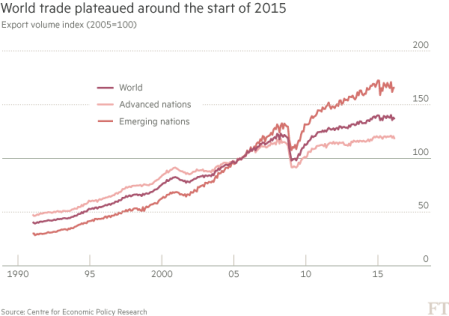

These deals are being negotiated in an environment where world trade is stagnating at best. Since the end of the Great Recession, world trade has grown no faster than the sluggish growth in world output – and that is unprecedented, in the post-war period, trade has always grown faster than output. It is another indicator that we are in a long depression and not a normal boom and slump.

So it would appear that ‘globalisation’ is stuttering and trade is offering no way out for capitalist economies in depression or stagnation.

And that is not a rosy scenario for the British negotiators of a new trade deals outside the European Union.

No comments:

Post a Comment