Stock markets have rallied in the last month, buoyed by the decision of the European Central Bank to plough yet more credit into the banks and lower further its policy interest rate. This was followed by the US Federal Reserve Bank’s monetary policy committee deciding not to raise its policy rate, claiming that it was worried about the state of global economy. Investors loved this and interest rates fell to below zero for some bonds. Now every financial institution is able to borrow as much as it wants for less than nothing.

So stock markets shot up, although they are still below the level of last summer. But there is little to indicate that the so-called real economy globally is improving – on the contrary. Global manufacturing output, as measured by investment bank, JP Morgan, is growing at only a 2.2% a year, less than half the usual trend, with the global manufacturing activity index (called the purchasing managers index – a survey of company intentions) hovering on the line (50 in the table below) between growth and contraction. If the PMI is right, then world manufacturing output is heading below 1% a year.

The key economy globally remains America. And last Friday, the final estimate for US real GDP in Q4 2015 was released. In the last quarter of 2015, the US economy expanded at a 1.4% annual rate and was up just 2% from the last quarter of 2014 and 2.4% for the whole year of 2015 compared to 2014. This is a better rate of growth than in the Eurozone or Japan, both at 1%. But it is still very weak. And there are signs that America’s economy is slowing down from even that low rate. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta has a pretty accurate forecasting tool for US economic growth. As of last week, its GDPNow forecast for the first quarter of 2016 (finishing this week) is for just a 1.4% annual rate of growth, the same as achieved at the end of 2015.

The European Central Bank has warned that the global economic recovery has weakened, meaning 2016 will be “challenging” – particularly in emerging markets. In its latest economic bulletin, the ECB says that global trade seems to have “lost momentum again” at the turn of the year – a worrying sign.

Readers of my blog know that I consider that business investment is the main driver of economic growth in a capitalist economy, not spending by households. According to JP Morgan’s economists, global equipment spending has decelerated significantly over the course of last year. Business investment globally (excluding China) was growing at just 2% at the end of 2015, barely enough to replace existing ageing plant and equipment. And JP Morgan reckons capital spending is growing at less than 1% a year globally in the first quarter of this year. Business investment fell 2.1% in the last quarter of 2015, the first quarterly decline for over three years.

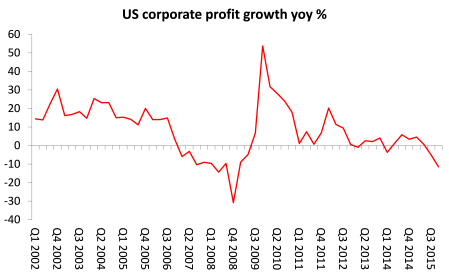

Behind the slowdown in corporate investment globally is the slowdown in corporate profits. I have tracked corporate profits growth in five major economies: the US, Japan, Germany, UK and China. The mean average annual growth of corporate profits for these major economies looks like this.

Globally, corporate profits stopped rising at the end of 2015. The situation is even worse in America. US corporate profits plunged 7.8% in Q4 2015 after a fall of 1.6% in the third quarter – so two consecutive quarterly falls. These are first two consecutive falls since the Great Recession of 2008. Compared to the last quarter of 2014, US corporate profits are 11.5% lower in the last quarter of 2015. Over the whole of 2015, corporate profits fell 3.1% compared to 2014.

Profits of top 500 US companies (those included in the S&P 500 index) fell 0.8% in 2015 from 2014 and were down 1.8% in the fourth quarter compared with a year earlier, according to analytics firm Estimize. JP Morgan reckons that “earnings growth is expected to be negative year over year in Q1 and Q2 of 2016 as earnings weakness spreads beyond energy”.

All this suggests that the global capitalist economy is slowing towards outright contraction. But not all agree. Gavyn Davies in the FT reports that the ‘Now forecast’ of his company Fulcrum Asset Management see better news. “Just when it all seemed very bleak, the global economy has shown some tentative signs of a rebound in recent weeks. The improved data significantly reduce recession risks in the near term…..This month, however, the data have failed to co-operate with the pessimists. Global activity growth has bounced back to 2.6 per cent, compared to a low point of 2.2 per cent a few weeks back. Much of this recovery has occurred in the advanced economies, with our nowcast for the United States showing a particularly marked rebound after more than 12 months of progressive slowdown.”

On the other hand, the IMF has hinted heavily that it will next month lower its 3.4 per cent growth forecast for the global economy with one of the main reasons being the failure of cheap oil to deliver a widely anticipated fillip to major economies. New IMF chief economist, Maurice Obstfeld reckons that historically low oil prices could trigger a series of corporate and sovereign defaults across the world. “The possibility of such negative feedback loops makes demand support by the global community — along with a range of country-specific structural and financial-sector reforms — all the more urgent.”

This would explain why many corporations are now having growing difficulty in servicing their debts, even though central banks have driven interest rates on debt to an all-time low. The energy industry, until the oil prices started plummeting, was regarded as one of the most profitable sectors. From 2006 to 2014, the global oil and gas industry’s debts almost tripled, from about $1.1tn to $3tn, according to the Bank for International Settlements. The smaller and midsized companies that led the US shale boom and large state-controlled groups in emerging economies were particularly enthusiastic about taking on additional debt.

It was a classic bubble, says Philip Verleger, an energy economist. “It was irrational investment: expecting prices to rise continually. Companies that borrowed heavily when prices were high are going to have a very tough time.” From 2004 to 2013, annual capital spending by 18 of the world’s largest oil companies almost quadrupled, from $90bn to $356bn, according to Bloomberg data. But the expectations of sustained high prices have vanished: crude for 2020 delivery is $52 a barrel. The oil price is now where it was in 2004, but most of the debt that was taken on in the boom years is still there.

Falling oil prices have hit other markets as risk appetite declines, says Hyun Song Shin, chief economist at the BIS. “When the credit cycle turns, you have a combination of higher volatility and tighter credit conditions,” he says. “It’s not the losses but the possibility of loss, and financial institutions pre-emptively cutting their exposure.”

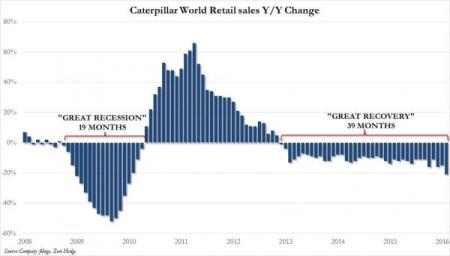

The contrast between how stock market values and the state of the real world is starkly revealed in the stock price of the world’s leading producer of industrial equipment, Caterpillar and the its actual global sales. The Caterpillar stock price looks like this.

But world retail sales for Caterpillar look like this.

Rising stock markets and very, very cheap credit; but low energy prices, rising corporate debt, slowing economic growth and falling investment and profits. Something must give.

No comments:

Post a Comment