The UK’s referendum on European Union membership takes place three months from today. How Britons vote will have an impact not just on Britain but also on Brussels. The ‘capital’ of the European Union is under pressure from the terrorist bombings, but Brexit would open up fault-lines in the EU ‘project’ itself. There could be implications for the survival of the European Union if one of its largest members should opt to leave. It sets a precedent that could be followed.

“Should I stay, or should I go”. The Clash

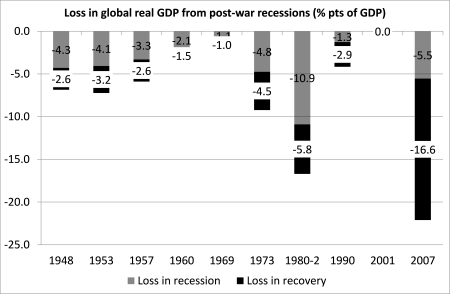

Should the British people vote to leave or stay in the European Union in the referendum in June? Before anybody answers that question, they ought to consider this. Whether Britons vote to leave or not is relatively small beer compared to the growing risk of a new world economic slump. That will have much larger consequences for the British people than Britain leaving the EU. Look at the damage that the Great Recession did to the major economies (graph below).

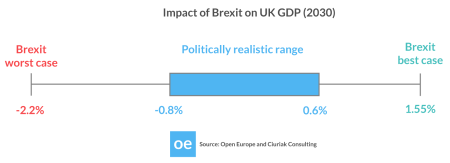

Some very pessimistic estimates have put the cost of leaving the EU for the UK economy at 10% of GDP. Some very optimistic estimates have put the gain from leaving at 10%. Even if this were the case, either way, that margin would still be less than the loss of income per person already caused by the Great Recession and the very weak economic recovery since, which currently stands at 14%. Open Europe, a think-tank that is itself neutral on the issue, reckons that, at worst, were the UK to leave the EU, its GDP would be 2.2% lower in 2030 than it would have been were the UK to stay in. And at best, it would be 1.6% higher.

Anyway, it is not a question what is ‘best for Britain’, but what is best for the British people. There’s a difference. Would British big business benefit from leaving the European Union, some 40 years after joining the club? Remember, right up to the global financial crash in 2007 onwards, the talk among the circles of British capital was whether to join the Eurozone or not, not whether to leave the EU. Very few thought the latter would benefit British capital.

Since the global financial crash and the ensuing Euro debt crisis, the view has changed. Today, the euro area is grappling with sluggish growth, the fallout from the euro crisis and an influx of refugees and migrants (and now terrorism – something previously aimed at Britain and the US). So, from the point of view of British capital, the gains from EU membership have begun to look less convincing.

Would British capitalism now do better outside the EU? The answer is that it depends, but on balance, probably not.

Sure, much of the original gains in removing trade, investment and labour barriers within the EU have been exhausted. But what would improve if Britain left? The EU institutions are certainly not holding the UK back from selling globally. Could Britain do better than Germany in world markets if it were outside the EU? Germany has a world trade volume that is more than three times the UK figure, but it is suffering from the economic slowdown in China right now. So why would British capital do better than Germany by opting for Asia or America over Europe for exports or investment? Indeed, the Asian emerging economy crisis may break just as Britain votes to leave the EU trading area.

There is a myth pushed by the EU-leavers that Britain can negotiate just as good trade terms as they had within the EU without all the EU regulations and budget funding for EU institutions. But the experience of European countries like Norway or Switzerland that have negotiated such agreements shows that with any trade deal comes obligations and conditions. Norway and Switzerland must abide by all EU single market standards and regulations, without any say in their formulation. They must agree to translate all relevant EU laws into their domestic legislation without consulting domestic voters. They contribute substantially to the EU budget. And they must accept unlimited EU immigration, resulting in a higher share of EU immigrants in the Swiss and Norwegian populations than in the UK! So overall, for British capital, there would be little difference outside than being in the EU, assuming it can negotiate a similar arrangement that Norway and Switzerland have.

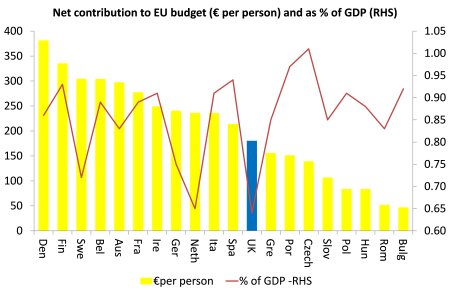

Also, European Economic Association (EEA) members such as Norway do not belong to the EU’s customs union. Consequently, Norwegian exports must satisfy ‘rules of origin’ requirements in order to enter the EU duty free and the EU can use anti-dumping measures to restrict imports from Norway, as occurred in 2006 when the EU imposed a 16% tariff on imports of Norwegian salmon. Also, EEA members effectively pay a fee to be part of the Single Market. In 2011 Norway’s contribution to the EU budget was £106 per capita, only 17% lower than the UK’s net contribution of £128 per capita (House of Commons 2013). So becoming part of the EEA would not generate substantial fiscal savings for the UK government and taxpayers. The UK’s contribution to the EU budget, after rebates, is not particularly high per head of population and low as % of GDP compared to other EU members.

The key interest of British capital is to preserve its hegemonic global position in financial services – and with the UK outside the EU that could come under threat. Britain’s specialisation in services – not only finance, but also law, accountancy, media, architecture, pharmaceutical research and so on – makes entry to the EU single market critical. If Britain refuses similar EU trading conditions to those made with Norway, its service industries could be locked out of the single market. The French, German, and Irish governments would be particularly delighted to see UK-based banks and hedge funds shackled by EU regulations, and see UK-based businesses involved in asset management, insurance, accountancy, law, and media forced to transfer their jobs, head offices, and tax payments to Paris, Frankfurt, or Dublin.

As it is, even within the EU, Britain is one the least regulated countries in the world, as previous Labour and Conservative governments have boasted. So getting rid of any EU regulations by leaving would have little added value for British capital. Anyway, even outside the EU, the UK would still be subject to 700 international treaties, as a member of the UN, WTO, NATO, IMF and World Bank, and subscribe to a swathe of nuclear test ban, energy, water, maritime law and air traffic treaties. The idea that leaving the EU would lead to a golden era of UK sovereignty and self-determination, is, it is fair to say, far-fetched at least. National sovereignty is a relative concept in modern imperialism.

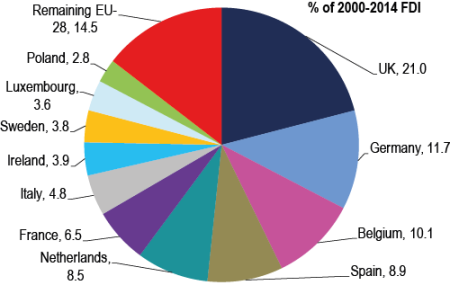

EU states may also try and usurp the UK’s position as the EU’s most popular destination for foreign direct investment. Over the past 15 years, the UK has received more than 20% of inward EU FDI, but without full access to the EU’s internal markets, future FDI flows into car factories or financial services hubs might be redirected and create jobs elsewhere in the EU.

So if Britain votes to leave the EU, it is unlikely to get as good trade and investment terms as before and Britain will still have to agree to most EU regulations and contributions, but without any say. And it could lose ground in financial services and in inward investment from America and Asia. Only if ‘freedom’ from EU institutions were to produce a sharp increase in productivity, investment and trade with the rest of the world, would these losses be overcome. On balance, that seems unlikely.

Indeed, in the short term, the uncertainty over the terms of any negotiations will mean a big reluctance of British capitalists to invest and for foreign investors to hold British financial assets. The pound sterling has already weakened and it would fall even more with a vote to leave. Any losses in investment and trade will add to losses in employment. Sure, maybe after two years of negotiations and, with perhaps further economic collapses in the Eurozone that threaten the Euro project itself, British capital might appear more attractive and the decision to leave the EU might seem right. But that’s a big if.

Would the majority of British people gain or lose from Britain leaving the EU? Britain’s Trade Union Congress (TUC) reckons that there are benefits for British workers from the EU. In a report, the TUC cites rights such as paid annual leave and fair treatment for part-time workers may be in danger that could be rolled back by a Conservative government (UK Employment Rights and the EU). “These are wide-ranging in scope, including access to paid annual holidays, improved health and safety protection, rights to unpaid parental leave, rights to time off work for urgent family reasons, equal treatment rights for part-time, fixed-term and agency workers, rights for outsourced workers, and rights for workers’ representatives to receive information and be consulted, particularly in the context of restructuring. And without the back-up of EU laws, unscrupulous employers will have free rein to cut many of their workers’ hard-won benefits and protections”.

But the TUC exaggerates. EU laws and directives like the 48-hour working week are hardly worth the paper that they have been written on, with many exemptions for employment sectors for example, like junior hospital doctors on a 72-hour week or the practice of many employers to get employees to sign a ‘waiver’ on working hours and conditions. The point is that most of our working conditions are determined by national laws and by the class struggle at the workplace, not by EU laws. Those battles have not been hindered or helped much either way by EU employment laws.

Even this isn’t the whole story, though, as it has become much more difficult in the UK for workers to enforce any employment law. The introduction of employment tribunal fees has seen a sharp drop in the number of cases being brought. As an employer in the UK there isn’t much employment law to fall foul of but, even if you do, the chances of being prosecuted for it are pretty remote.

Then there is the question of immigration. Leaving the EU would supposedly allow Britain to block cheap labour from eastern Europe flooding into the country and lowering wages and conditions. Or so the argument goes. But any trade deal with the EU would involve free movement of EU labour as Norway and Switzerland must do.

Reducing immigration will not improve the situation for working people already in the UK. Migrants often fill the gaps in the labour market that Britons won’t or can’t fill. To take one example, strawberries, are now available in the shops for much longer. They are picked by migrant workers who return to Eastern Europe at the end of the season. Care work is another industry heavily populated with migrant labour. Migrants often perform low paid, dirty work that British workers would be reluctant to perform.

It’s true that mass immigration can also cause pressure on education, housing and social services, particularly for working class people. But the actions of the Conservative government in reducing public spending, privatising schools and the NHS has a much bigger effect on services.

So whether Britain is in or out of the European Union will make little difference to the majority of people in the UK. What does matter is the health of the economy, the level of wages and employment and the state of public services. That does not depend on Britain’s membership of the EU.

The euro debt crisis in Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy etc is mainly to do with the crisis in capitalism since 2007 and not really to do with the institutions of the EU, cumbersome, bureaucratic and undemocratic as they are; or to do with the policies of the EU leaders for Europe. The neo-liberal, pro-austerity measures applied by the EU Commission are the very same policies adopted by the national governments of Europe on their people. EU policy is no more neo-liberal and pro-big business than is the policy of successive British governments of the last two decades, Conservative or Labour.

That’s something the Greek people recognised last year. In their referendum on whether to accept the Troika ‘bailout’ last July, despite huge pressure from the EU leaders and Greek capitalism, the Greeks voted no because they opposed further austerity. But the vast majority of Greeks still wanted to stay in the EU and even keep the euro currency. For them, the issue was not ‘in or out the EU’, but ‘yes or no’ to further cuts in living standards.

Leaving the EU would probably be marginally bad for British capital and there would be little or no gain for British Labour. But the debate is a total distraction and an irrelevance from the issues that do affect people’s lives, the crisis in global capitalism and what to do about it. Under global capitalism, no one country can protect its citizens from pollution, climate change, economic slumps and world wars. That needs global cooperation and policy action by socialist governments – something we don’t have. Avoiding the damage from another major global slump, which is now on the horizon, however the British people votes in June, is way more important.

Two years ago, I made three predictions: that the Conservatives would be re-elected in the general election in May 2015; that the Scots would vote against independence from the UK; and that the British would vote to stay in the EU. So far, it is two out of three. I expect the third prediction to be confirmed by the end of June.

No comments:

Post a Comment