The recent announcement of the Bank of Japan (BoJ) that it would introduce a negative interest rate (NIRP) for commercial banks holding cash reserves is the final admission that monetary policy supported by mainstream economics and implemented by central banks globally has failed.

The main economic policy weapon used since the global financial crash and the ensuing Great Recession to avoid another Great Depression of the 1930s has been zero interest rates (ZIRP), then ‘unconventional’ monetary measures or ‘quantitative easing (QE)’ (increasing the quantity of money supply to banks), all fixed to inflation targets of 2% a year or so. ZIRP and a virtually unlimited supply of cash (QE) were supposed to kick-start the global economy into action, so that eventually capitalism and market forces would take over and achieve ‘normal’ and sustained economic growth and fuller employment.

But QE and ZIRP have failed to achieve their inflation (and growth) targets. On the contrary, the major economies are close to deflation, as commodity and energy prices plunge and prices of goods in the shops and on the internet slide. Deflation has its good and bad side. Sure, it lowers the cost of many things but it also raises the real burden of debt repayments for those who borrow. And if prices are falling continually, it breeds an unwillingness to spend or invest in the expectation that it will be cheaper to wait. Deflation is a symptom of a weak economy, but also a cause of making it weaker. Deflation can become a debt deflationary spiral.

So now we have NIRP. It started with the Swiss, then the Swedes and more recently the European Central Bank and now the Bank of Japan. Now about one-quarter of all interest rates are below zero! And we have only just begun with this latest monetary tool. BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda announced there is “no limit” to monetary easing and that he would invent new tools rather than give up his goal of 2 per cent inflation. “Going forward, if judged necessary, it is possible to cut the interest rate further from the current level of minus 0.1 per cent,” said Kuroda. “The constraint of the ‘zero lower bound’ on a nominal interest rate, which was believed to be impossible to conquer, has been almost overcome by the wisdom and practice of central banks, including those of the Bank of Japan,……It is no exaggeration that [ours] is the most powerful monetary policy framework in the history of modern central banking,” he said.

The ‘wisdom’ of central banks – really? ‘Most powerful’? NIRP will fail in the same way that ZIRP and QE has. Take Sweden. There, the Riksbank, the central bank, has applied NIRP with zeal for some time. What has been the result? Inflation in the prices of goods and services has not returned. Instead, cheap credit and penalties for holding cash (negative rates) have pushed banks into lending for property and stock market speculation, not productive investment. Swedish non-financial credit now stands are 281% of GDP, a rise of 25% on the pre-crisis peak and up from 212% a decade ago. House prices have risen by a quarter nationally and 40% in Stockholm over the past three years, stretching earnings ratios to extremes (house prices are 11.7x earnings in the capital).

Far from curing deflation and restoring growth, NIRP will only exacerbate the sizeable debt burden that the major economies have built up in a desperate attempt to avoid a ‘Great Depression’ since 2009. To bail out the banks and avoid a severe collapse in incomes and employment, governments borrowed hugely. Sovereign debt, as it is called, rose to record post-1945 levels. But the private sector, particularly the corporate sector, also expanded its debt. Cheap central bank money flowed into the so-called emerging market miracle economies of Asia and Latin America. But now they are in recession, leaving a debt burden to be serviced, mainly in appreciating dollars.

And as China and emerging economies slow or drop into a slump, the demand for exports from Europe, Japan and North America has slid away. Take the European powerhouse, Germany. While Chinese exports only account for 6% of total German overseas sales, adding in Asia this rises to 10%. That might still seem small, but is a potentially large drag on GDP where net trade has been contributing an average of 0.6% pts to the 1.5% pts of growth recorded over the last six years.

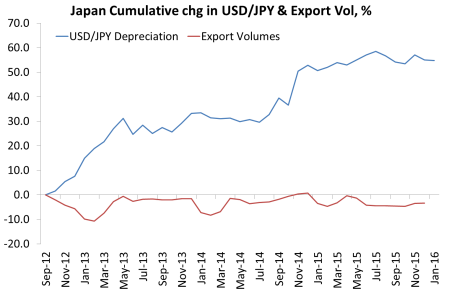

It’s a similar story in Japan. The BoJ’s policy of ZIRP, QE and now NIRP has succeeded in weakening the yen against the dollar. But it has failed to boost exports because most other Asian currencies have fallen too and now the Chinese yuan is under pressure. Despite a 55% fall in the yen against the dollar in just three years of BoJ policy, there has been zero increase in export volumes.

Nevertheless, the dominant economic tool of the mainstream and major governments is still monetary policy, with its last stand in NIRP. The US economy is still plodding along at about a 2% real growth rate, better than most and official unemployment has come down. US Fed chief Janet Yellen claims to be confident that sustainable improvement in real GDP is here. Yet all the recent economic data lend serious doubt to that forecast and the aim of the Fed to hike interest rates in 2016. So there is even talk that the US Federal Reserve may adopt NIRP if everything goes pear-shaped in the US.

In its annual stress test of the US banks for 2016, the Fed said it will assess the resilience of big banks to a number of possible situations, including one where the rate on the three-month U.S. Treasury bill stays below zero for a prolonged period. “The severely adverse scenario is characterized by a severe global recession, accompanied by a period of heightened corporate financial stress and negative yields for short-term U.S. Treasury securities”, the central bank said in announcing the stress tests last week. New York Fed President William Dudley said last month that policy makers were “not thinking at all seriously of moving to negative interest rates. But I suppose if the economy were to unexpectedly weaken dramatically, and we decided that we needed to use a full array of monetary policy tools to provide stimulus, it’s something that we would contemplate as a potential action.”

Fed Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer said that foreign central banks that had resorted to negative interest rates to stimulate their economies had been more successful than he anticipated. “It’s working more than I can say I expected in 2012,” he told the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. “Everybody is looking at how this works,” he added. Working well? Really? Sweden?

Radical Keynesian, Richard Koo summed up the NIRP option as “an act of desperation born out of despair over the inability of quantitative easing and inflation targeting to produce the desired results… the failure of monetary easing symbolizes crisis in macroeconomics”. RichardKoo_2Feb2016-1

As I have shown before in a previous post, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes also gave up on monetary policy. Having advocated lowering interest rates and ‘unconventional’ monetary easing, he eventually concluded that it was not working and moved onto to fiscal policy – in essence more government spending. This is also the answer for Koo.

Keynes in the 1930s was disappointed that governments, particularly the US and the UK, did not adopt his policy of deficit financing and government spending, let alone his more radical suggestion of the ‘socialisation’ of investment to replace the failure of capitalists to invest. And modern Keynesians like Paul Krugman, Larry Summers, Simon Wren-Lewis or Brad Delong, while promoting monetary easing big time since 2008, have increasingly become disillusioned and joined Richard Koo in advocating fiscal spending to avoid ‘secular stagnation’ and deflation. What puzzles the Keynesians is why governments, as in the 1930s, will not go down this road.

For the Keynesians, running up debt (public sector debt) is not a problem: one man’s debt and is one woman’s credit is the argument. But debt does matter, as I have argued in previous posts. Debt must be serviced and repaid by real production: money does not come out of nothing forever. The corporate sectors of China, Asia, Brazil, Russia and Europe are finding that out now. Deficit financing and rising public debt will not kick-start an economy that has low profitability and high corporate debt. And in near deflationary economies, there is a real burden in servicing that debt.

Monetary policy has failed; NIRP will not work. But neither will a more radical Keynesian deficit financing plan. Both fail to recognise that it is profits versus the cost of capital and debt that sets the pace of economic expansion or contraction in a capitalist economy.

Globally, corporate profits have been falling and in the major economies even the largest companies are seeing falling earnings and sales. In the US, 43% of the top 500 companies have reported their financial results for the last quarter of 2015. On average, sales were down 2.5% over the end of 2014 and profits were down 3.7%. In Europe, 17% of the top 600 companies have reported and sales were down 6.5% and earnings 11.7%. In Japan, 45% of the top 225 companies reported a fall in sales of 2.5% and profits down 9.3%.

A new round of ‘creative destruction’ is coming globally and ZIRP, QE and NIRP will not stop it.

No comments:

Post a Comment