There is a growing talk among mainstream economists and the financial media of a new global economic recession. Until the last few weeks, the locus of this new slump has been focused on China. But, as I have argued in a previous post, it is unlikely to start there. Much more important to the world economy is the largest economy in the world in terms of national output and financial fire-power, the US.

In the last few weeks, there has been a continuous series of poor data for the US economy: falling manufacturing output, weakening business sentiment and capital goods orders and falling corporate profits. And globally, international agencies by the week seem to announce reduced forecasts for economic expansion.

The latest of these agencies, after the IMF, the World Bank and the OECD, is the United Nations. In its report on global economic perspectives, it concluded that “the world economy stumbled in 2015 and only a modest improvement is projected for 2016/17 as a number of cyclical and structural headwinds persist”. 2016wesp_full_en

UN economists downgraded their final estimate for global growth in 2015 from 2.8% to just 2.4% – remember the average prior to the Great Recession for global growth was 4-5% a year. Naturally, like the other agencies, it expects an improvement this year and next: “The world economy is projected to grow by 2.9 per cent in 2016 and 3.2 per cent in 2017, supported by generally less restrictive fiscal and still accommodative monetary policy stances worldwide.” But then each year these more optimistic forecasts are dashed and revised.

The UN also confirmed a key indicator of the Long Depression, that I call the period since the end of the Great Recession of 2008-9. As Professor Joseph Stiglitz put it in a recent article: “Moreover, the UN report clearly shows that, throughout the developed world, private investment did not grow as one might have expected, given ultra-low interest rates. In 17 of the 20 largest developed economies, investment growth remained lower during the post-2008 period than in the years prior to the crisis; five experienced a decline in investment during 2010-2015.” Indeed, the average growth rate in developed economies has declined by more than 54% since the crisis. An estimated 44 million people are unemployed in developed countries, about 12 million more than in 2007, while inflation has reached its lowest level since the crisis.

Stiglitz went onto consider “what’s holding back the world economy?” He noted what some of us have been saying for years: that quantitative easing by central banks, as used in the US, Japan, the UK and belatedly in the EU, has failed to boost growth and investment. The problem was that the banks used the cheap cash from central banks not to lend onto companies to invest or households to spend, but to build up their cash reserves or buy government bonds or their own shares.

As Stiglitz concluded: “Clearly, keeping interest rates at the near zero level does not necessarily lead to higher levels of credit or investment. When banks are given the freedom to choose, they choose riskless profit or even financial speculation over lending that would support the broader objective of economic growth.” Of course, this is something that many Marxist economists have been saying for years – in opposition to the hopes of Keynesian economists like Paul Krugman or Noel Smith. Moreover, what could provide a better case for the public takeover of banking systems in the major economies so that credit can be directed productively and not for bank profits?

Stiglitz also directs our attention to the massive reversal of capital inflows to so-called emerging economies. “An unintended, but not unexpected, consequence of monetary easing has been sharp increases in cross-border capital flows. Total capital inflows to developing countries increased from about $20bn in 2008 to over $600bn in 2010. Very little of it went to fixed investment. This year, developing countries, taken together, are expected to record their first net capital outflow – totalling $615bn – since 2006.” Actually, according to the Institute of International Finance, the outflow figure was even larger, with net capital outflows of an estimated $735bn during 2015, the first year of net outflows since 1988!

As another international agency, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), put it in its latest quarterly review, the surge in lending to emerging markets that helped fuel their own — and much of the world’s — growth over the past 15 years has come to a halt, and may now give way to a “vicious circle” of deleveraging, financial market turmoil and a global economic downturn. “In the risk-on phase [of the global economic cycle], lending sets off a virtuous circle in financial conditions in which things can look better than they really are,” said Hyun Song Shin, head of research at the BIS, known as the central bank of central banks. “But flows can quickly go into reverse and then it becomes a vicious circle, especially if there is leverage.”

The BIS reported that the total stock of dollar-denominated credit in bonds and bank loans to emerging markets — including that to governments, companies and households but excluding that to banks — was $3.33tn at the end of September 2015, down from $3.36tn at the end of June. This was the first decline in such lending since the first quarter of 2009, during the global financial crisis, according to the BIS.

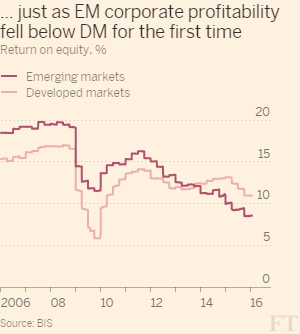

In previous posts I have pointed out that the huge rise in credit to emerging markets threatens a major bust especially if the profitability of capital should begin to fall in these economies.

And that is just what is happening. The return on equity capital in advanced capitalist economies is below levels before the Great Recession but it partially recovered from 2009 and only started to fall in the last year or so. But profitability in emerging economies has been falling since 2012 and is now below that of advanced economies for the first time.

The head of IIF, Caruana commented, “The issue is not just for emerging markets. It is spilling back into developed markets. The broader financial markets are recoiling from risk, and that spreads across all markets. The problem now is that the real economy is being affected.”

In my last post, I took up the issue of negative interest rate policy (NIRP). This is the new policy forced upon central banks to try and get the world capitalist economy out of this Long Depression. Zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) has failed, quantitative easing (QE) or printing money has failed, so now let’s charge banks and other financial institutions for keeping cash and try to force them to lend or invest. Several small central banks had already adopted NIRP (Switzerland and Sweden) but last week, one of the largest, the Bank of Japan, applied NIRP.

The BoJ vote to do so was only 5-4 because the minority were not convinced that it would work. Indeed, NIRP could make things worse, they thought. NIRP is the last throw of the dice in monetary policy and if it did not work in getting the Japanese economy out of its stagnation, the Bank would be seen to be helpless. And why should NIRP work any better in stimulating business investment than ZIRP or QE?

Within weeks, it is becoming clear that NIRP is not working. Japanese government ten-year bond yields dropped into negative territory. This means that banks and other corporate investors would prefer to pay the Bank of Japan and the government for holding bonds for the next decade rather than spend cash or invest! And that behaviour is happening increasingly globally. The volume of government bonds trading below zero interest has now reached $6trn, or one-third of the entire global sovereign bond market!

So what is to be done? Martin Wolf, the Keynesian economic journalist for the UK’s FT, asked the question in a recent article. His answer seemed to be more of the same ‘unconventional’ monetary policy. “It is crucial to recognise that something more unconventional might have to be done”. Another recession was bound to come along and doing nothing about it was not an option.

Wolf went through the various options that I have discussed above and eventually concluded that the only one left with the possibility of success was “helicopter money” — dropping money directly into people’s bank accounts in so that they spent more. This is similar to the People’s QE advocated by some of the current leftist Labour opposition in the UK and has been mooted before by heterodox economists. I have discussed this option in a previous post when it was proposed by maverick Bank of England economist, Andy Haldane.

In my view, it won’t work because it assumes that what is wrong with the capitalist economy and the reason for the continued Long Depression and the prospect of another slump is the Keynesian explanation of a ‘lack of demand’. For Keynesians, you can create extra spending through money creation. This leads to increased employment and then to increased income and growth and thus to more profits. But the reality of the capitalist system is the other way round. Only if profitability is sufficient, will investment increase and lead to more jobs and then incomes and consumption. The demand for money will rise accordingly. Artificial money creation by fiat from the government does not get round this – as the experience of ‘quantitative easing’ has already shown.

Instead, we must look at what is happening with profits and profitability. And as I have shown in several previous posts, the profitability of business capital in the major economies is near historic post-1945 lows and the limited recovery in profitability since 2009 has come to an end. Indeed, global corporate profit growth has ground to a halt and is now falling in China, the UK and most important in the US.

Last week, the investment bank, JP Morgan, noted that US corporate profit margins (the share of profit in each unit of national output) have started to fall back from its record highs. After the slowdown in US productivity growth to near zero, as reported last week, JPM’s economists now expect US corporate profits to fall by 10% this year.

And here is the rub. As I and (a few) other Marxist economists have argued, JPM points out that every time there is such a large fall, an economic recession is not far behind, because such a fall is seldom not followed by an economic recession. I quote: “this week’s larger-than-expected productivity drop in 4Q15 points to a 10% drop in corporate profits from year-ago levels. A double-digit decline in profits is a rare event outside recessions, having been recorded only twice in the last half century”.

JPM has raised the probability of a US economic recession from 10% to 25% in 2016. And that probability is greater than 50% before 2017 is out.

I have commented on the possibility of a new global recession in previous posts. My view is that it is due and will take place in the next one to three years at most. Some mainstream economists are now forecasting a more than 50% chance for 2016. Citibank economists reckon that there is a 65% chance in 2016.

This doom-mongering is dismissed by others. Bill McBride from Calculated Risk trashed those recession mongers who think it is on the cards for next year. Says McBride: “For the last 6+ years, there have been an endless parade of incorrect recession calls. The manufacturing sector has been weak, and contracted in the US in November due to a combination of weakness in the oil sector, the strong dollar and some global weakness. But this doesn’t mean the US will enter a recession. The last time the index contracted was in 2012 (no recession), and has shown contraction a number of times outside of a recession. Looking at the economic data, the odds of a recession in 2016 are very low (extremely unlikely in my view).”

Maybe it won’t be in 2016. But the factors for a new recession are increasingly in place: falling profitability and profits in the major economies and a rising debt burden for corporations in both mature and emerging economies. And the Fed set to hike the cost of borrowing in dollars. As I said before, it’s a poisonous concoction.

Can we avoid this slump? Stiglitz’s answer to avoid this is to ‘direct’ banks to lend for investment or household spending and to introduce “large increases in public investment in infrastructure, education, and technology” to be financed by higher taxes on ‘monopolies’. No doubt, increased public investment would help to compensate for the failure of capitalist investment. But the world is capitalist: governments are not going to boost public investment if it means higher taxes for corporations, reducing their profitability even more. So even this moderate policy for more public investment is a challenge to capitalism in an environment of low profitability, rising debt and depressed growth – something that Keynesian/Marxist Michel Kalecki at the end of the Great Depression of the 1930s pointed out.

Wolf’s ‘helicopter money’ and Stiglitz’s tax-funded public investment are poor options. It is not the banking system that has to be by-passed or directed but the capitalist system of production for profit that has to replaced by planned investment under common ownership.

No comments:

Post a Comment