The US Federal Reserve bank is planning to raise its basic interest rate at its 15 December monetary policy meeting. This will be the first Fed hike since 2006. That fact alone shows how long and how deep has been the impact of the global financial crash of 2007-2008, the subsequent Great Recession of 2008-9 and the ensuing and seemingly unending long depression of below trend economic growth since.

For six years, the Fed has held its interest rate near zero to ‘save the banks’ from meltdown, to avoid debt depression like the 1930s and to revive the economy with cheap credit.Ben Bernanke, the Fed chief at the time, continues to argue that this easy and ‘unconventional’ monetary policy did that trick. Bernanke has recently published a book defending his strategy and does interviews for the same.

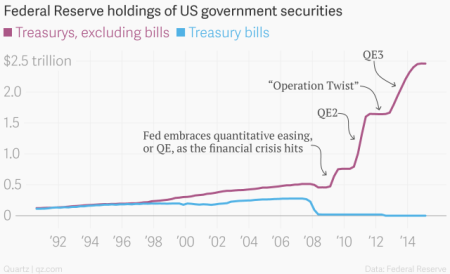

In this blog, I have analysed the success or otherwise of quantitative easing where it has been applied in the US, Japan and now in the Eurozone. It has been a dismal failure in reviving the major economies. It has been a great success in supporting a boom in the stock and bond markets and in financing new credit bubbles in emerging economies.

Apparently, a majority of Fed monetary policy makers reckon that, at last, the US economy is growing fast enough to ‘tighten’ labour markets and even raise the possibility of rising inflation perhaps eventually beyond the 2% target that Fed looks to. But that conclusion is debatable at the very least.

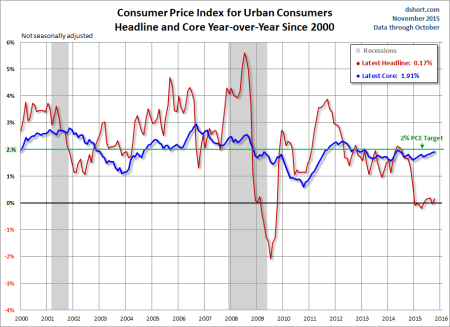

It’s true that the unemployment rate has halved to 5% from its peak of 10% at the depth of the Great Recession, but it is still above the pre-crash lows. And inflation remains well below the Fed target. Headline inflation which includes energy and food prices is near zero, and even excluding these items, ‘core’ inflation, although rising is still below the Fed target at 1.9%. And if you look at the prices that average Americans pay for the goods and services they use, based on the personal consumption expenditure (PCE), then inflation is very low.

Moreover, real GDP growth remains pretty pathetic at around 2.2% a year on average, well below the average of 3.3% a year before. The ‘trend gap’ shows no sign of being bridged. Indeed, what is happening is that the official economic bodies are lowering their estimates to potential GDP growth towards the actual level of growth so that the ‘output gap’ disappears.

In other words, it is being admitted that the US economy is now set on a permanent path of lower long-term growth, based a low growth in population (despite one million net immigrants a year) and very low productivity growth (as business investment growth slows).

The damage to the US economy from the Great Recession has left a permanent scar; what is called ‘hysteresis’. In a new study, Professor Laurence Ball of Johns Hopkins University (http://www.nber.org/papers/w20185), from a sample of 23 high-income countries, concludes that losses of potential output as a result of the Great Recession ranged from zero in Switzerland to more than 30 per cent in Greece, Hungary and Ireland. In aggregate, he concludes, potential output this year was thought to be 8.4 per cent below what its pre-crisis path would have predicted. This damage from the Great Recession is, he notes, much the same as if Germany’s economy had disappeared.

This measures the permanent loss of resources and value caused by capitalist slumps.

Indeed, work by Keynesian economists Larry Summers, Olivier Blanchard (ex-IMF chief economist) and Eugenio Cerrutti found that a high proportion of recessions, or about two-thirds, are followed by lower output relative to the pre-recession trend even after the economy has recovered. In about one-half of those cases, the recession is followed not just by lower output, but by lower output growth relative to the pre-recession output trend. That is, as time passes following recessions, the gap between output and projected output on the basis of the prerecession trend increases. They suggest important hysteresis effects and even “superhysteresis” effects (the term used by Laurence Ball for the impact of a recession on the growth rate rather than just the level of output).

This can be looked at from various angles of economic theory: from the neoclassical Wicksellian view that the ‘natural rate’ of interest (or profit) is permanently lower; from the Keynesian one that the US economy is in ‘secular stagnation’ and/or a permanent ‘liquidity trap’; or from a Marxist one that the US (and major economies) is locked into a depression because of low profitability created by excessive accumulation of tangible capital and financial debt in the past.

The first two theories in some way suggest that the Fed should not hike rates in case they take the cost of borrowing either above the ‘natural rate’ or burst the credit bubble and push the economy into a deeper liquidity trap. The Marxist view is that, just as zero interest rates and quantitative easing made little difference in restoring a low profitability, high debt economy, so raising them will solve nothing either.

The Keynesian answer (at least among those Keynesians like Krugman, Summers, DeLong and Wren-Lewis) is: keep going with the easy money policy but add to it a round of government spending, financed by government borrowing. You see, the main cause of the Great Recession was ‘lack of demand’ and the main cause of the subsequent weak recovery or depression was the application of ‘austerity’ (i.e. cuts in government spending in trying to balance the books as though an economy was like household finances). Rising debt does not matter because one person’s debt is another’s asset.

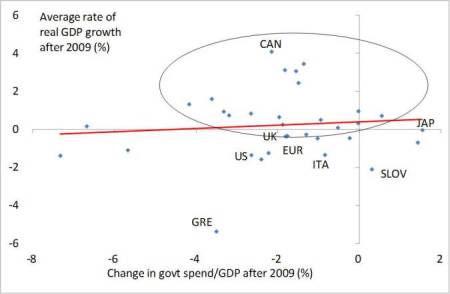

Well, there are a number of questions there. First, did governments in the major economies apply austerity? Well, some did and some did not too fiercely despite the neo-classical rhetoric of many finance ministers. Second, did more or less austerity correlate with slower or faster growth? The Keynesians say it did. They proclaim the power of the Keynesian multiplier, namely that one unit of extra government spending over taxes will deliver a multiple of one unit of real GDP, especially in times of slump. They usually cite a ratio of 1.5 times.

The evidence for this is weak and a matter of intense debate, although only this week, Paul Krugman made another attempt to prove that austerity was the cause of global weakness. I did a correlation between fiscal deficit expansion by various governments against an increase in real GDP and found little correlation, especially if Greece is removed.

And in the latest study of the impact of austerity on growth, Alberto Alesina and Francesco Giavassi found that “fiscal adjustments based upon cuts in spending are much less costly, in terms of output losses, than those based upon tax increases. ….spending-based adjustments generate very small recessions, with an impact on output growth not significantly different from zero.” And “Our findings seem to hold for fiscal adjustments both before and after the financial crisis. We cannot reject the hypothesis that the effects of the fiscal adjustments, especially in Europe in 2009-13, were indistinguishable from previous ones”. In other words, cutting government spending (austerity) had little effect on the real GDP growth rate and that applied to the post-crisis ‘austerity policies of European governments.

G Carchedi and I have considered the mechanism of government tax and spending policies on economic growth from the Marxist viewpoint. We started from the premiss that economic growth in capitalist economies depends on an expansion of business investment and that depends ultimately on the profitability of those investments. So we looked at the multiplier effects of government spending, taxation and borrowing on growth through the prism of profitability – a Marxist multiplier, we called it.

Our Marxist multiplier analysis revealed that it was very unlikely that extra government spending, whether financed by taxes of borrowing, would boost profitability in the business sector and therefore raise capitalist investment and economic growth.

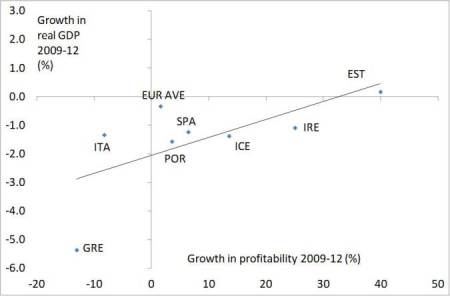

I have tested our premiss that it is the profitability of business capital that matters not government spending. I found that there was a significant positive correlation between changes in profitability of capital and economic growth, unlike the lack of correlation between more government spending and growth, as the Keynesians claim, at least in a slump.

That again tells me that if we want to know what is going to happen in the major capitalist economies we must look at the key indicators of business investment and the profitability of capital, not at inflation, employment or the level of ‘austerity’ as mainstream economists do.

So what are the prospects for global capitalism on those Marxist criteria and what is the likelihood of a new slump as the Fed prepares to hike? I have discussed these questions ad nauseam on this blog in the past. But let us consider the latest evidence.

At the recent meeting of the G20 in Turkey, apart from discussing the mess in the Middle East and the migration crisis in Europe, the ministers reaffirmed their pledge or expectation that the major economies by an extra 2% by 2018. What an ‘additional’ 2% of G20 GDP means is difficult to judge. But anyway it is really a sick joke.

Far from accelerating, global growth is slowing down further. In its twice-yearly outlook, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) cut its forecast for global economic growth to 2.9% in 2015 and 3.3% in 2016, down from 3.0% and 3.6%, respectively.

Presenting the outlook in Paris, OECD secretary general Angel Gurría said: “The slowdown in global trade and the continuing weakness in investment are deeply concerning. Robust trade and investment and stronger global growth should go hand in hand.” Catherine Mann, OECD chief economist said: “Global trade, which was already growing relatively slowly over the past few years, appears to have stagnated and even declined since late 2014. This is deeply concerning. Robust trade and global growth go hand in hand….“The growth rates of global trade observed so far in 2015 have, in the past, been associated with global recession.”

We also have the preliminary real GDP figures for the most important capitalist economy in the world, the US. In third quarter of 2015 (June to September) US economic expansion slowed sharply. The economy grew at a 1.5 per cent pace annualised pace in the three months to September, down from 3.9 per cent in the second quarter. The US economy has expanded in real terms over the last 12 months by just 2%, down from 2.7% in Q2 and business investment slowed to its lowest yoy rate for over two years; at an annual rate of 2.1% compared with 4.1% in Q2. And investment in new plant actually dropped 4% and investment in software and such rose at the slowest pace since 2013.

Meanwhile Japan’s economy contracted in the third quarter. Real GDP declined an annualized 0.8 percent, following a revised 0.7 drop in the second quarter. Again, the biggest worry was the weakness in business investment. This was the fifth ‘technical recession’ since Japanese PM Abe launched his ‘Abenomics’ and quantitative easing programmes. And in the Eurozone economic growth slowed to just 0.3% in Q3, from 0.4% in Q2.

And then we have the so-called emerging economies. I have reported on their demise in several previous posts. The policy of easy money and quantitative easing did not only lead to a stock and bond market boom in the major advanced economies, it also led to a similar boom in emerging economies as Asian, Latin American and ‘emerging’ European corporations borrowed heavily from cash-rich Western banks at cheap rates, mostly in dollars, to generate mainly a property and construction boom. Emerging market corporations now have debts near 100% of GDP on average, matching those for corporations in the advanced capitalist economies. But the commodity price boom upon which much of growth was based has collapsed. Global demand for oil and basic metals has slumped and this has spilt over into the demand for Asian exports. Export prices have slumped, currencies have dived and yet debts remain, mainly in dollars. And now the Fed is set to hike the cost of borrowing dollars.

So does all this mean we are heading for a new global slump? Well, I have raised the risk that a Fed rate hike could be the trigger for a new slump, just as it was in 1937 when it brought to an end to recovery from 1932 during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Only the preparations and beginning of the world war ended that slump.

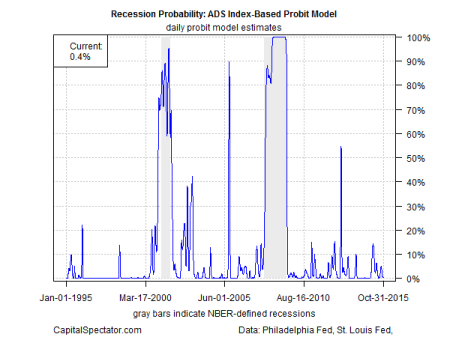

The strategists of capital are not stupid. They have tried to estimate the likelihood of a new recession. Goldman Sachs pointed out that the current economic expansion — beginning in July 2009 — was now 76 months old. Using data since 1950, they calculate that the unconditional odds that a six-year-old expansion will avoid recession for another four years—and mature into a 10-year-old expansion—are about 60%. So the odds of recession over the next year are only 10-15%. And mainstream economic indicators for recessions using a range of economic variables suggest little likelihood of a slump in the US.

But this sort of indicator is pretty useless and it is backward looking, so recessions are on you before the data indicate them. And mainstream economics never forecast the Great Recession anyway. Indeed, we know that all the leading international economic agencies, the leading economists and investment gurus were predicting faster growth in 2007-8 as the global financial crash unfolded.

Moreover, in my view, modern capitalist cycles of slump to slump have not been just six years or less, but generally 8-10 years: 1974-5, 1980-2, 1990-2, 2001, 2008-9. If that were to hold again, then the next slump would not be due to start before next year at the earliest. And if the Fed’s rate hikes are to have an impact, they won’t be felt on the cost of debt and investment for at least six months.

It is best to consider the Marxist indicators that I have referred to: profitability and profits and business investment. There has been some debate in Marxist economic circles that profitability is not low or falling and that there is an excess not a dearth of profits in the major economies. I have discussed these arguments that the capitalist world is ‘awash with cash’ in previous posts. All I can add is that cash and profits are the not the same and profits and profitability are not either. I have not measured US profitability for 2015 and final proper data for 2014 is only just becoming available, but 2014 showed a decline, with rate still below the peak of 2007 and the higher peak of 1997.

I have shown before in previous posts that global corporate profit growth has nearly ground to a halt and in the US on some measures, it has gone negative.

The latest earnings results for the top 500 companies in the US confirm that both revenue and profits fell in the most recent quarter.

And as I have shown before, where profits go, business investment is likely to follow, with a lag.

Watch this space.

No comments:

Post a Comment