Most years I attend the London conference of the Historical Materialism journal. This brings together academics and others to present papers and discuss issues from a generally Marxist viewpoint. This year I presented a paper on whether rising inequality causes crises under capitalism (Does inequality causes crises). My session was well attended and the audience included many of the small band of Marxist economist s around at the moment.

The gist of what I said was this. Rising inequality of income and wealth in the major economies has become a popular thesis among both mainstream and heterodox economists. The thesis is founded on the arguments that wages as a share of GDP have been falling in the major economies. This creates a gap between demand and supply, or a tendency to underconsumption. That gap was filled by an explosion of debt, particularly household debt. It is also encouraged financial institutions to engage in riskier financial investments that exposed them to eventual disaster. The credit boom fuelled a housing bubble but eventually that burst and the house of cards came tumbling down. QED?

My paper attempted to refute this theory of crisis with the following simple points.

1) Private consumption has not been weak or did not collapse, causing a demand gap – on the contrary in most economies and particularly in the US, consumption to GDP during the so-called neo-liberal period rose to record highs.

2) The major international slumps of 1974-5 and 1980-2 cannot be laid at the door of rising inequality because it did not rise at the time. Indeed, most Marxist economists at least agree that the 1970s slump was the result of a squeeze on profits not a squeeze on wages. The rising inequality thesis cannot apply as a general theory of crises.

3) Actually, the share of labour income in national income when non-work income is included (net social benefits) did not fall in the neo-liberal period. Labour income share kept pace with consumption share and debt was not needed to fill a ‘demand gap’.

4) A fall in consumption does not take place before slumps, so the house of cards did not collapse because of a fall in consumer demand. It is a fall in investment that provokes a slump and during a slump, it is investment not consumption that falls the most.

5) There are many studies that show no connection between rising inequality and credit or banking and general crises under capitalism.

6) There are better causal connections and correlations between profitability and investment and economic growth than between inequality, consumption and growth. Profits call the tune.

For a fuller account of these arguments, see my HM paper.

There did not seem too much opposition to my thesis, although there were questions on my data. The discussion at the session came from an accompanying paper by Jim Kincaid, formerly economics lecturer at Leeds and other universities. Jim’s paper, which was apparently just an excerpt from an upcoming article in the HM journal, aimed to analyse why investment has been faltering in modern economies, particularly since the end of the Great Recession. Above all, he wished to question or refute the theory that Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is the underlying cause of crises, as advocated by myself, Carchedi, Kliman and several others.

Jim Kincaid said he supported the position of Dumenil and Levy that each major slump or ‘structural crisis’ in the history of modern capitalism has had a different cause. The 19th century Great Depression was the result of falling profitability; but the Great Depression of the 1930s was not, and was caused by rising inequality and ‘crazy investment’. The 1970s slump was the result of falling profitability but the Great Recession was again caused by rising inequality and ‘crazy financial investment’. These arguments of D-L have been dealt with in this blog before and are also taken up in my paper on inequality presented.

Interestingly, Professor Riccardo Bellofiore, who also presented a different paper in the session on translating Marx’s concepts, commented in passing that he reckons Marx’s law of profitability has been dead in the water since the late 19th century depression because since then the ‘counteracting factors’ have overcome the law ‘permanently’. This is a strange conclusion given all the recent evidence cited in this blog for a secular fall in profitability globally since Marx’s time. Next year, G Carchedi and I will publish a book, a collection of papers from scholars around the world that will confirm Marx’s law of profitability with empirical evidence.

But what was the essence of Kincaid’s critique of those ‘monocausal’ advocates of Marx’s law of falling profitability as the cause of crises under capitalism? To quote Kincaid’s abstract: “I argue: (1) empirically, the thesis of falling rates of profit in the major economies is based on an uncritical use of not always reliable government data; (2) Harvey and other sceptics are correct to stress that central to the present crisis is the inability of the global system to absorb large quantities”.

Kincaid argues that it was not a falling rate of profit, or too little profit that caused the Great Recession and subsequent weak recovery, but too much. Capitalist firms have built up huge cash reserves from profits that they are not investing productively. So the problem is one of how to ‘absorb’ these surpluses, not how to get enough profit. This also shows, according to Kincaid, that the causal sequence for crises, namely falling profits to falling investment to falling income and employment is nonsense because we have rising profits and falling investment.

Thus we have from Kincaid a thesis of surplus absorption that echoes not only that of David Harvey he refers to but also the view of Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran of the Monthly Review ‘school’ that monopoly capitalism has sunk into stagnation because it cannot dispense with ever-increasing surpluses of profit. The fallacies in this view have been dealt with by many authors.

But what about the issue of cash mountains in major non-financial companies? Close readers of my blog will know that I have dealt with this issue in several previous posts.

Let me now reiterate some of the points made in those posts (the data have not been updated given the time, but will not have changed much). It is true that cash reserves in US companies have reached record levels, at just under $2trn – see graph below. (All figures come from the US Federal Reserve’s flow of funds data.) The rise in cash looks dramatic. But also note that this cash story did not really start until the mid-1990s. In the glorious days of the 1950s and 1960s when profitability was much higher, there was no cash build-up.

But the graph is misleading. It is just measuring liquid assets (cash and those assets that can be quickly converted into cash). Companies were also expanding all their financial assets (stocks, bonds, insurance etc). When we compare the ratio of liquid assets to total financial assets, we see a different story.

And according to Credit Suisse’s latest figures, US corporate cash to total assets (financial and tangible) has risen but still way below the 1950s and 1960s.

US companies reduced their liquidity ratios in the Golden Age of the 1950s and 1960 to invest more or buy stocks. That stopped in the neoliberal period but there was still no big rise in cash reserves compared to other financial holdings. And that includes the apparent recent burst in cash. The ratio of liquid assets to total financial assets is about the same as it was in the early 1980s. That tells us that corporate profits may have been diverted from real investment into financial assets, but not particularly into cash.

Comparing corporate cash holdings to investment in the real economy, we find that there has been a rise in the ratio of cash to investment. But that ratio is still below where it was at the beginning of the 1950s.

And remember within these aggregate averages lies the reality that just a few mega companies hold most of the cash while thousands of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) hold little cash and much more debt. Indeed, a minority are re4ally ‘zombie’firms just raising enough profit to service their debt.

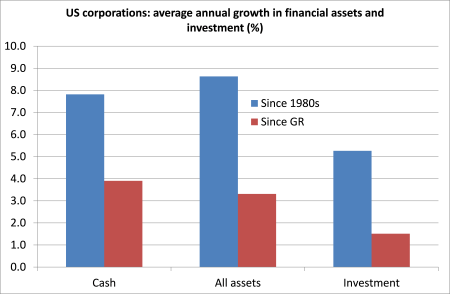

Why does that cash to investment ratio rise after the 1980s? Well, it is not because of a fast rise in cash holdings but because the growth of investment in the real economy slowed in the neoliberal period. The average growth in cash reserves from the 1980s to now has been 7.8% a year, which is actually slower than the growth rate of all financial assets at 8.6% a year. But business investment has increased at only 5.3% a year in the same period, so the ratio of cash to investment has risen.

Interestingly, if we compare the growth rates since the start of the Great Recession in 2008, we find that corporate cash has risen at a much slower pace (because there ain’t so much cash around!) at 3.9% yoy. That’s slightly faster than the rise in total financial assets at 3.3% yoy. But investment has risen at just 1.5% a year. So consequently, the ratio of investment to cash has slumped from an average of two-thirds since the 1980s to just 40% now.

It does seem that there has been build-up of cash relative to short-term debt, particularly in the credit boom of 2000s. This suggests that corporations were borrowing more and needed to increase their cash buffers as a safety measure.

So companies are not really ‘awash with cash’ any more than they were 30 years ago. What has happened is that US corporations have used more and more of their profits to invest in financial assets rather than in productive investment. Their cash ratios are pretty much unchanged, suggesting that there is not a ‘wall of money’ out there waiting to be invested in the real economy.

In a recent paper in the Journal of Finance (2009), Why firms have so much cash, the authors found that there was “a dramatic increase from 1980 through 2006 in the average cash ratio for U.S. firms.” But interestingly, cash hoarding was not taking place among firms who paid high dividends to their shareholders. On the contrary. The authors argue that the “main reasons for the increase in the cash ratio are that inventories have fallen, cash flow risk for firms has increased, capital expenditures have fallen, and R&D expenditures have increased.” In order to compete, companies increasingly must invest in new and untried technology rather than just increase investment in existing equipment. That’s riskier: So companies must build up cash reserves as a sinking fund to cover likely losses on research and development. Rising cash is more a sign of perceived riskier investments than a sign of corporate health.

In a recent paper, Ben Broadbent from the Bank of England noted that UK companies were now setting very high hurdles for profitability before they would invest as they perceived that new investment was too risky. Broadbent put it: “Prior to the crisis finance directors would approve new investments that looked likely to pay for themselves (not including depreciation) over a period of six years – equivalent to an expected net rate of return of around 9%. Now, it seems, the payback period has shortened to around four years, a required net rate of return of 14%.” And remember that the current net rate of return on UK capital is well below that figure at about 11%.

Broadbent continued: “Even if the crisis originated in the banking system there is now a higher hurdle for risky investment – a rise in the perceived probability of an extremely bad economic outcome….In reality, many investments involve sunk costs. Big FDI projects, in-firm training, R&D, the adoption of new technologies, even simple managerial reorganisations – these are all things that can improve productivity but have risky returns and cannot be easily reversed after the event.”

So it seems that companies have become convinced that the returns on productive investment are too low relative to the risk of making a loss. This is particularly the case for investment in new technology or research and development which requires considerable upfront funding for no certainty of eventual success.

And here is the rub. Just at this time when Jim Kincaid raises the issue of huge cash reserves and suggests that the cause of crises is due the difficulty of ‘absorbing’ profits, US corporate earnings are falling and profit growth has ground to a halt. Cash reserves are set to fall. The latest tally by Thomson Reuters of earnings by the S&P 500 in the US finds that earnings are on course to fall 1.3 per cent on the back of revenues down 3.6 per cent. In Europe, Stoxx 600 companies are on course to report a drop of 8.2 per cent in revenues compared with a year ago and earnings falls of 4.3 per cent year on year. And, as I have shown on numerous occasions, corporate profits in the major economies are now hardly growing at all.

Yes, large firms in the capitalist sector of the major economies have been hoarding more cash rather than investing over the last 20 years or so. But they are not investing so much because profitability is perceived as being too low to justify investment in riskier hi-tech and R&D projects, and because there are better and safer returns to be had in buying shares, taking dividends or even just holding cash. Also many companies are still burdened by high debt even if the cost of servicing it remains low.

The point is that the mass of profits is not the same as profitability and in most major economies, profitability (as measured against the stock of capital invested) has not returned to levels seen before Great Recession. And the high leveraging of debt by corporations before the crisis started is acting as a disincentive to invest and/or borrow more to invest, even for companies with sizeable amounts of cash. Corporations have used their cash to pay down debt, buy back their shares and boost share prices, or increase dividends and continue to pay large bonuses (in the financial sector) rather than invest in productive equipment, structures or innovations.

I conclude that the cash reserves of major companies is not an indication that the cause of crises is due to inability to absorb ‘surplus profit’ but due to an unwillingness to invest when profitability remains low and debt is relatively high. That is the cause of this Long Depression. Marx’s law holds. Too much profit, or too little? Too little. Too much cash or too much debt? Too much debt.

No comments:

Post a Comment