Martin Wolf, the Keynesian economic journalist in an article in the UK’s Financial Times, has highlighted a paper by two economists at the US Federal Reserve, Joseph Gruber and Steven Kamin that showed a widening gap between corporate savings (or profits) and corporate investment in most of the major economies (Gruber corporate profits and saving).

This gap, technically called ‘net lending’ by corporations, Wolf describes as a global ‘savings glut’. The notion of a “savings glut” was first mooted by former Federal Reserve chief, Ben Bernanke, back in 2005. He argued that economies like China, Japan and the oil producers had built up big surpluses on their trade accounts and these ‘excess savings’ flooded into the US to buy US government bonds, so keeping interest rates low.

Martin Wolf and other Keynesians have liked this notion because it suggests that what is wrong with the world economy is that there is too much saving going on, causing a ‘lack of demand’. This is the proposition that Wolf recently pushed in his latest book.

In his book, Wolf concludes that the cause of the Great Recession “was a savings glut (or rather investment dearth); global imbalances; rising inequality and correspondingly weak growth of consumption; low real interest rates on safe assets; a search for yield; and fabrication of notionally safe, but relatively high-yielding, financial assets.”

And yet it was not falling consumption or rising savings that provoked the Great Recession, but falling investment (as even Wolf partially recognises in the quote). Investment is by far the most important part of the dynamics of a capitalist economy. As Wolf says: “companies generate a huge proportion of investment. In the six largest high-income economies (the US, Japan, Germany, France, the UK and Italy), corporations accounted for between half and just over two-thirds of gross investment in 2013 (the lowest share being in Italy and the highest in Japan).”

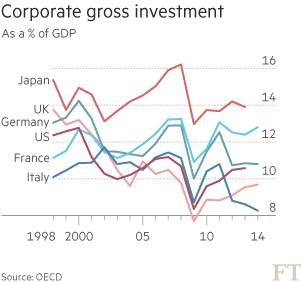

So is the gap between corporate savings and investment caused by a ‘glut of savings’? Well, look at the graph provided by Wolf, taken from the OECD.

With the exception of Japan, since 1998, corporate savings to GDP have been broadly flat. And for Japan, the ratio has been flat since 2004. So the gap between savings and investment cannot have been caused by rising savings. The second graph shows what has happened.

We can see that there has been a fall in the investment to GDP ratio in the major economies, with the exception of Japan, where it has been broadly flat.

So the conclusion is clear: there has NOT been a global corporate savings (or profits) ‘glut’ but a dearth of investment. There is not too much profit but too little investment. The capitalist sector has reduced its investment relative to GDP since the late 1990s and particularly after the end of the Great Recession. And when you read closely the Fed paper cited by Wolf, this is also the conclusion. Gruber and Kamin demonstrate that rates of corporate investment “had fallen below levels that would have been predicted by models estimated in earlier years”.

Joseph Gruber and Steven Kamin conclude their paper with a puzzle: “what is causing this paucity of investment opportunities, and what are its implications for future investment and growth?” Wolf cites various reasons for weak corporate investment: the ageing of societies thus slowing potential growth; globalisation motivating relocation of investment from the high-income countries; technological innovation reducing the need for capital; or management not being rewarded for investing but instead for maintaining the share price.

Many of these causes have been cited before and I have discussed them in previous posts. But most interestingly, after citing the Federal Reserve paper, Wolf fails to mention the conclusion of the Fed authors on the cause of weak investment in the last 15 years. I quote: “We interpret these results as suggesting that investment in the major advanced economies has indeed weakened relative to what standard determinants would suggest, but that this process started well in advance of the GFC itself. Finally, we find that the counterpart of declines in resources devoted to investment has been rises in payouts to investors in the form of dividends and equity buybacks (often to a greater extent than predicted by models estimated through earlier periods), and, to a lesser extent, heightened net accumulation of financial assets. The strength of investor payouts suggests that increased risk aversion and a precautionary demand for financial buffers has not been the primary reason firms have cut back investment. Rather, our results are consistent with views that, for any number of reasons, there has been a decline in what firms perceive to be the availability of profitable investment opportunities”.

So the cause of weak investment in productive assets and a switch to share buybacks and dividend payments and some cash hoarding was primarily due to a perceived lack of profitability in investing in productive assets. This confirms the conclusions reached by other studies that I have cited in previous posts dealing with the fallacious argument that corporates are ‘awash with cash’.

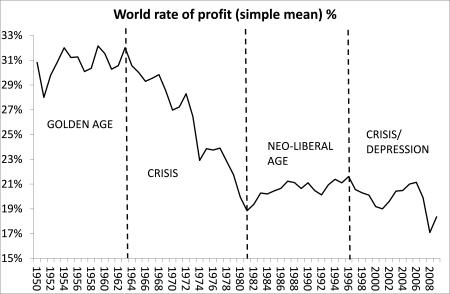

I would suggest that we already have an answer to the question of why ‘profitable investment opportunities’ are scarce. Overall profitability in the major capitalist economies peaked in the late 1990s and has not recovered to that level since. I have discussed this in a recent paper on the world rate of profit (Revisiting a world rate of profit June 2015). But here is a graph based on the work of Esteban Maito cited in that paper. Global profitability peaked in the later 1990s and has not recovered.

As a result, companies have used their ‘savings’ to invest not in productive assets like factories, equipment or new technology that could boost productivity growth (which has slowed to a trickle), but instead paid out more dividends to shareholders, boosted top executive pay and bought back shares to boost their prices. And much of this has been done by multinationals borrowing more at near zero rates, while shifting cash into offshore tax havens to avoid tax.

In my view, this clearly lends support to Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as an explanation of weak investment in the major capitalist economies since 1998. Marx’s law would suggest that any fall in the rate of profit should be accompanied by a rise in the organic composition of capital (the ratio of the value of capital equipment to the wages of the labour force) faster than any rise in the rate of surplus value (the profit extracted from the labour force). In my recent paper, I show that in the current ‘depression’ period since 2000, the organic composition of capital rose 41%, well ahead of the rise in the rate of surplus value at 7%. So the rate of profit has fallen 20%. ‘Profitable investment opportunities’ have shrunk.

We are told by the likes of Ben Bernanke and echoed by Martin Wolf that today’s problem of ‘secular stagnation’ is being caused by a ‘global savings glut’ in surplus countries and even in G7 countries. In other words, there was too much surplus (value) to ‘absorb’. But this is a fallacy. There was not a ‘savings glut’ but an ‘investment dearth’. As profitability fell, investment declined and growth had to be boosted by an expansion of fictitious capital (credit or debt) to drive consumption and unproductive financial and property speculation. The reason for the Great Recession and the subsequent weak recovery was not a lack of consumption (consumption as a share of GDP in the US has stayed up near 70%) but a collapse in investment.

No comments:

Post a Comment