The final figures for US real GDP in the second quarter of this year (April to June) were released at the end of last week. They showed that the US economy was growing at an annual rate of nearly 4% (3.9%) in the summer after yet another poor first (winter) quarter of just 0.6% growth. So, compared to summer 2014, the US economy has expanded by 2.7%. Indeed, the US economy has been growing at that sort of rate for the last four quarters.

However, before the cry comes that, finally, American capitalism is back on a sustained trend in growth similar to that before the Great Recession, there are some caveats.

First, the growth in gross domestic income (as opposed to product) is much slower. GDI slowed to just 2.1% yoy in Q2 2015. Gross domestic income is the income received by American homes and businesses. If gross domestic product grows more, it means more of the value of that domestic production has gone to foreign businesses and abroad.

Second, the reason that GDP growth seems to have picked up in the second quarter is that for virtually the first time since the Great Recession, the government sector expanded. In Q2, America’s states (not the federal government) contributed 12% towards US economic growth, instead of reducing it, as healthcare spending rose.

Also, although business investment rose, it contributed a relatively smaller proportion towards GDP growth (20%) compared to previous quarters and years since the end of the Great Recession. Growth was mainly achieved by households buying more cars, electrical goods and spending more on healthcare (Obama-care?) and taking out mortgages to buy more homes. US growth is consumer-driven and debt-financed (with interest rates at all-time lows).

But the most sobering caveat is that in the current quarter (Q3) just ending this week, US real GDP growth looks likely to have slowed down sharply from that near 4% rate to something close to 2%. Indeed, the Atlanta Federal Reserve real GDP forecasting indicator, which has been very accurate in the recent years, forecasts just a 1.4% growth rate for Q3.

And the forecast slowdown is not really surprising because economic data in this current quarter has been very weak: factory orders, retail sales, durable goods orders, industrial production etc.

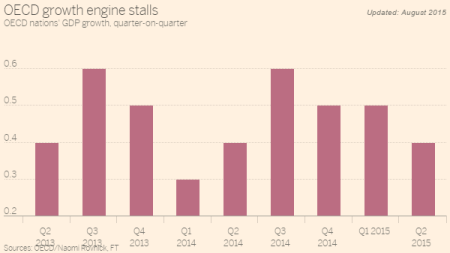

Alongside this US slowdown, the major capitalist economies, both advanced and so-called ‘emerging’, have been slowing. According to the OECD, economic growth in the 34 major advanced capitalist economies grew by only 0.4% in the second quarter of 2015 from the first quarter – a deceleration from the 0.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter growth achieved in the first three months of this year. Year-on-year GDP growth for the OECD area remained unchanged at 2 per cent in the second quarter of 2015.

And in this quarter of the year, global growth seems to have slowed even more. The UK economy, which was the leader in the top G7 economies, may struggle to achieve 2% growth, while Germany, France, Japan and Italy will be closer to 1%. And the major ‘emerging’ economies are diving. We have all heard about China slowing fast, leading to slowdowns in Australia, New Zealand and most of south-east Asia.

But on top of the ‘China crisis’, there are outright slumps in Brazil and Russia and low growth in Turkey, South Africa and Indonesia. Even India’s real GDP growth, which has been racing along at about 7% a year, turned down this quarter. The global crawl is turning paralytic.

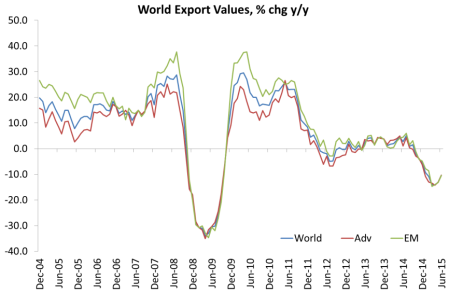

World trade is heading back to the depths of the Great Recession.

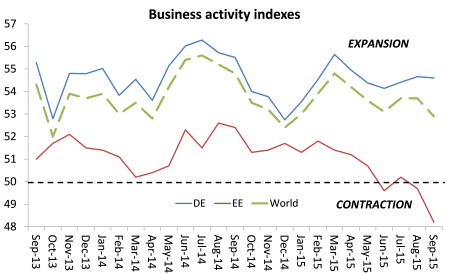

Indeed, the latest update of my global business activity index (based on purchasing managers indexes around the world), shows a sharp contraction in activity among emerging markets.

So it is no wonder that the US Federal Reserve drew back from its planned hike in interest rates in September. The Fed statement specifically highlighted the global economic slowdown as the reason for holding off (at least until December). The Fed, along with many mainstream economists, that hiking US rates would spill over into higher cost of borrowing and debt servicing and possibly trigger a collapse in stock and bond markets globally – something I have highlighted before as another ‘1937’.

Several financial strategists are already worried that stock markets are overvalued compared to future earnings and profits. And that’s what the ‘Warren Buffet’ indicator of the value of corporate stock to GDP shows – significant over-valuation.

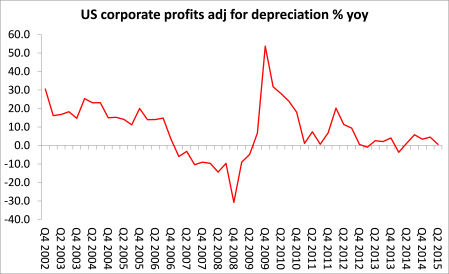

That’s where the latest data on corporate profits come in. In Q2 2015, US corporate profits, after taking into account inventories and depreciation (in other words, new profits), rose just 0.6% compared with summer 2014 and, after tax, actually fell 0.6%.

And there was a sharp increase in dividends paid out to shareholders by corporations. So the available profit for investment has dropped 4.6% compared to summer 2014. Moreover, two-thirds of the rise in profits in Q2 2015 accrued to the financial sector with just one-third to productive sectors.

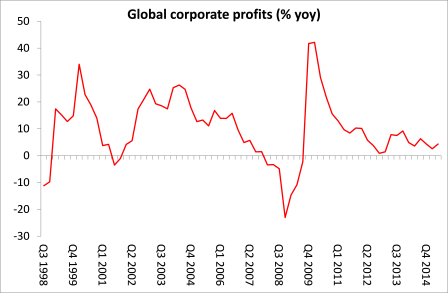

Globally too, corporate profit growth remains low. Indeed, without a sharp rise in Japanese corporate profits in Q2, growth would have been a trickle. Indeed, Chinese industrial profits fell nearly 9% in August compared to August 2014.

Looking out longer term, a new report from the management consultant, McKinsey (MGI Global Competition_Executive Summary_Sep 2015) reckons that “the world’s biggest corporations have been riding a three-decade wave of profit growth, market expansion, and declining costs. Yet this unprecedented run may be coming to an end”. According to McKinsey, the global corporate-profit pool, which currently stands at almost 10% of world GDP, could shrink to less than 8% by 2025—undoing in a single decade nearly all of the corporate gains achieved relative to the world economy during the past 30 years.

From 1980 to 2013, vast markets opened around the world while corporate-tax rates, borrowing costs, and the price of labour, equipment, and technology all fell. The net profits posted by the world’s largest companies more than tripled in real terms from $2 trillion in 1980 to $7.2 trillion by 2013, pushing corporate profits as a share of global GDP from 7.6% to almost 10%.

But McKinsey reckons that profit growth is coming under pressure. This could cause the real-growth rate for the corporate-profit pool to fall from around 5% to 1%, practically the same share as in 1980, before the boom began. So the great neo-liberal period of corporate profit recovery is over. According to McKinsey, margins are being squeezed in capital-intensive industries, where operational efficiency has become critical. Meanwhile, some of the external factors that helped to drive profit growth in the past three decades, such as global labour arbitrage (globalisation) and falling interest rates, are reaching their limits.

As I have argued on many occasions, from the movement in profits flows the movement in investment and then to overall economic growth. If profits, both globally and in the US, start to fall, then eventually so will investment and the slow economic growth recorded in the major capitalist economies since 2009 could turn into a new slump.

Economic recessions or slumps seem to occur about every 8-10 years in the post 1945 period (1958-60, 1970, 1974-5, 1980-2, 1990-2, 2001, 2008-9), the so-called business cycle. If that cycle is to reoccur, then the next recession is due between 2016 and 2018 (given that the last began in 2008).

I have argued that we can discern a profit cycle as well as a business cycle (see my book, The Great Recession). The cycle of profitability is about 32-36 years, trough to trough, in the US. The last trough was in 1982, followed by the so-called neoliberal revival in profitability until 1997-00. The current downwave should therefore trough no later than 2018. If this is right – any scientific analysis worth its salt should make predictions that can be proved wrong (or right) – then profitability in the US should be heading downwards pretty soon. All this suggests a major slump within 1-3 years.

The world economy is still crawling along, but interest rates are at all-time lows and stock markets are way overvalued. Any shift up in the cost of borrowing and any shift down in profitability would turn that crawl into crash.

No comments:

Post a Comment