More than a million protesters took to the streets of Brazil on Sunday to call for the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, as anger intensified over increasing economic hardship and the multibillion-dollar corruption scandal at state oil company Petrobras (where money was siphoned off for the use of political parties, mainly the governing one, while Rousseff was chair of Petrobras!). “I’m tired of corruption — we’re all tired of paying high taxes and seeing no return for society,” said Cristina Araújo, a systems analyst.

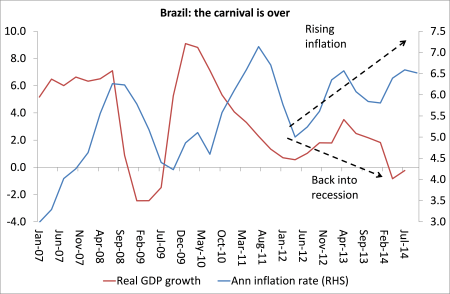

Brazil’s economy, presided over by a social-democrat administration that claims to stand for the poor and for labour, is in disastrous decline. Brazil’s currency, the real, is at a 12-year low. The economy is contracting and real incomes are falling.

The government’s answer has been to introduce neo-liberal reforms and fiscal austerity. Since Brazil recorded its first primary budget deficit in more than a decade last year, newly and narrowly elected Rousseff has tried to introduce tax and benefit cuts to correct the country’s public finances. The tax cuts are to benefit the corporations and the benefit cuts hit the poor.

However, she has met tough resistance, not only among ordinary Brazilians but also from coalition parties in Congress, which has been paralysed by infighting over the Petrobras scandal. Three weeks ago, truck drivers set up roadblocks across a third of the country in protest over higher fuel taxes, among other costs, leaving supermarket shelves bare and disrupting soyabean shipments. The government was forced to give into most of their demands.

Brazilians are also outraged by poor public services and rising inflation, which hit the highest level in a decade in February even as the country heads for another technical recession this year. Many states are also struggling with water shortages and the possibility of energy rationing after the country’s worst drought in 80 years.

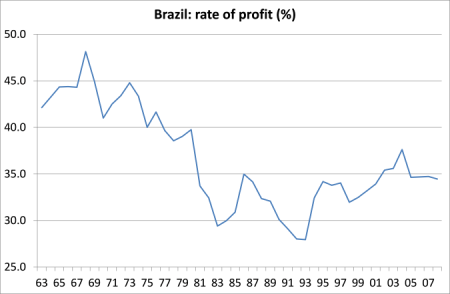

What’s gone wrong? Well, I can refer to my post of July 2013 with almost little amendment (https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/07/02/brazil-the-carnival-is-over-2/). In that post, I showed that the profitability of Brazil’s dominant capitalist sector had been in secular decline, imposing continual downward pressure on investment and growth.

Between 1963 and 2008, the rate of profit fell by about 19%. This secular fall was really the product of the very large decline in the rate of profit from 1963 to the early 1980s and 1990s. Over these 20 years or so, the rate of profit fell over 30% while the organic composition rose 23% and the rate of exploitation fell 17% – a classic example of Marx’s law of profitability at work.

But from the mid-1990s, Brazil’s ruling elite adopted neo-liberal policies designed to restore the rate of profit. Between 1993 and 2004, the rate of profit rose 35%. The organic composition of capital rose 20% as foreign investment flooded into industry (autos, chemicals and petroleum), but the rate of exploitation rose even more, up 55%, as more Brazilians entered the industrial and agro processing labour force with intensive capitalist production methods, while wages were held down.

Brazil became a major agricultural producer and exporter to the world market. Leading exports include soybeans and products, beef, poultry meat, sugar, ethanol, coffee, orange juice, and tobacco. Brazil’s agrifood sector now accounts for about 28% of the country’s GDP. Brazil’s is now the world’s third-largest agricultural exporter (in value terms), after the US and the EU. Rapid export growth was accompanied by changes in the composition of agricultural exports away from tropical products to processed products – up the value-added scale. Processed products now account for about three-fifths of agricultural exports.

And Brazil, like some other emerging economies, benefited from some other favourable external factors that supported the neo-liberal policies at home. Food commodity prices rose. In a way, it was like the discovery of North Sea oil that helped Britain’s Thatcher government in the 1980s. The income windfall to Latin America from persistently high commodity prices over the past decade was unprecedented. It averaged 15% of domestic income on an annual basis and close to 90% on a cumulative basis. So there was a lucky combination of rising commodity prices driven by Chinese demand; of productivity gains as the rate of exploitation rose; and an expansion of employment from the rural areas. All this boosted profitability and growth for a decade. After the 2002 crisis, GDP growth averaged above 4% per year until 2010. This led to significant improvements in living standards and life in general.

Under the government of former president Lula and the commodity boom, there were some important gains for the working class: a social protection system, increasing credit at low interest rates for workers and universalising health and education. The Bolsa Familia, or family allowance programme, is the most visible face of these policies. Between 2004 and 2011, the number of families benefiting from income transfers more than doubled, from 6.5 million to 13.3 million, representing nearly one-quarter of the population. In the more isolated regions, payments under this programme have become the principal engine of the local economy. Another pillar of government policy, adopted through negotiations with the unions, was to raise the minimum wage and associated pension. It went up by 211% in nominal terms between 2002 and 2012, for a real inflation-discounted increase of 66%. Unemployment rate plunged from 12.3% to 6.7% and the labour force expanded at a 1.6% yearly rate.

But the iniquities of capitalist development remained embedded in the system. Inequality of income and wealth in Brazil remains at extreme levels, exceeded only by post-apartheid South Africa. Despite the boom of the last decade, average household net-adjusted disposable income in Brazil is still way lower than the OECD average of $23,047 a year – and that’s the average. Over 16 million people are still living in what is deemed extreme poverty, with monthly incomes of below 70 reais (about $33). Some 80% of men are in paid work, compared with 56% of women and 12% of employees work very long hours, higher than the OECD average of 9%, with 15% of men working very long hours compared with 9% for women.

Around 7.9% of people reported falling victim to assault over the previous 12 months, nearly twice the OECD average of 4.0%. Brazil’s homicide rate is 21.0, almost ten times the OECD average of 2.2, one of the highest in the world at 21 per 100,000. Violence is concentrated among young people and over the past decade and a half, violence – including armed violence – has become a major social problem in the country. And Brazil’s regional disparities remain very high: average GDP per capita varies from just 46% of the national average in the Northeast region to 34% above the average in the Southeast.

Moreover, Marx’s law of profitability was still at work. From 2004, the rate of profit began to fall (down 8% to 2008 and more since), as wages shot up and the rate of exploitation dropped 25%. It was only the continued boom in commodity prices that kept growth going. When the global slump came in 2008-9, the emerging capitalist economies could not avoid the consequences.

In the case of Brazil, it seemed that rising commodity prices plus a deliberate policy by the government to increase state-financed investment had enabled Brazil to avoid the worst of the slump compared to others. But prices for Brazil’s key agricultural exports began to falter from 2011 onwards. In the last few years, global commodity prices have fallen back sharply and profitability began to fall further. Now Brazil’s export profitability is some 20% below its best years before 2004.

Brazil’s GDP growth has consequently slowed since 2011. There has been a sharp fall in manufacturing investment and exports over the past two years. While public investment increased by 0.4% points to 5.4% of GDP, it has not been enough to compensate for the fall in the ratio of private investment to GDP from 14.3% to 12.7% last year. Industry has not even returned to its pre-2008 crisis production level.

The government has tried to get private sector investment going through tax cuts and incentives for the corporate sector but only at the cost of running up a deficit on its budget. Interest costs on the public debt have been mounting, forcing the government to cut subsidies to transport, housing and education on which the majority rely. It was the last straw to spend huge amounts on football and the Olympics (partly to boost capitalist sector profits) at the expense of basic public services.

Subsequent unrest has prompted the government to make some concessions, but it has no intention of reversing its neo-liberal policies. Profitability in the capitalist sector will not recover without further hits to living standards. But austerity and making labour pay for the failure of Brazil’s capitalist sector is not working. That’s because economic growth will remain low as long as the world economic recovery remains weak. This brings to the surface the blatant corruption and political patronage, like dirty scum floating to the top of polluted water.

No comments:

Post a Comment