There is an irony in the face-off between the Euro leaders, the ECB and the Syriza government in Greece. It is that, in a world economy that has crawled along at a below trend growth rate since the end of the Great Recession in mid-2009 (see my posts, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/08/29/the-us-recovery-the-long-depression-and-pax-americana/), there are signs that those Eurozone economies that have been in depression (Spain, Portugal, Greece, Slovenia etc) are beginning to show some signs of life after death.

It is a major premise of a Marxist view of investment and growth under capitalism that it depends on profitability of capital and also on the return on new investment. And profitability will fall and/or stay low if there is an existing stock of corprorate capital and debt (represented partly by weak companies with old technology and high debt) that only makes enough income to just cover operations and debt servicing. Companies in this position are what have been called zombie companies.

There were a huge number of these zombies in the weaker Eurozone economies. As sales collapsed in the Great Recession, these ‘uncompetitive companies’ (mostly small but also large) struggled on for a while, but eventually succumbed to bankruptcy and elimination, laying off huge swathes of labour. This is the process of the destruction of capital values that capitalism periodically goes through to ‘cleanse’ itself and restore profitability.

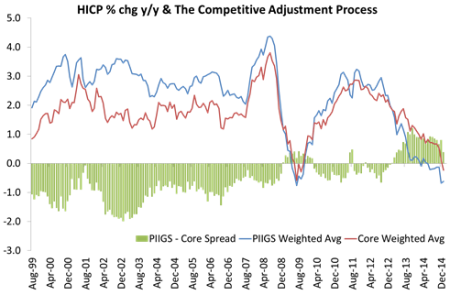

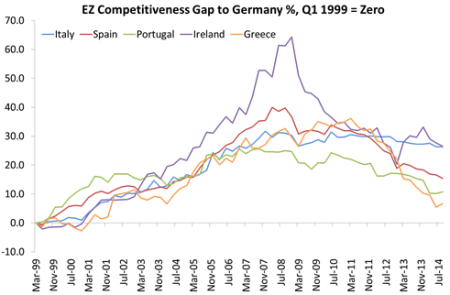

Well, there are now signs that, in the weakest Eurozone economies, this process is beginning to ‘work’. The ‘competitiveness’ of the capitalist sector in Ireland, Spain, Portugal and even Greece, has improved sharply relative to the stronger Eurozone economies of Germany etc.

Take Spain. The boom before the Great Recession was mainly based on a credit-fuelled expansion in the property sector.

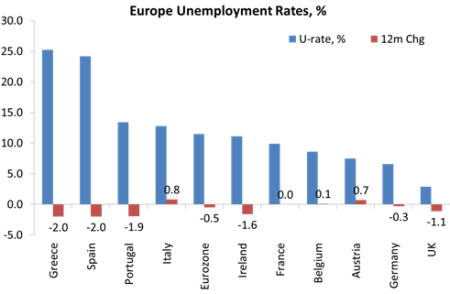

But now there are signs that the huge hangover of ‘dead’ property left in the Great Recession is beginning to be stripped down, taken over or written off. Spain’s capitalist sector is beginning to look meaner and cleaner. There is still some way to go but in all these weak Eurozone economies, the unemployment rate has peaked and begun to fall (very slowly).

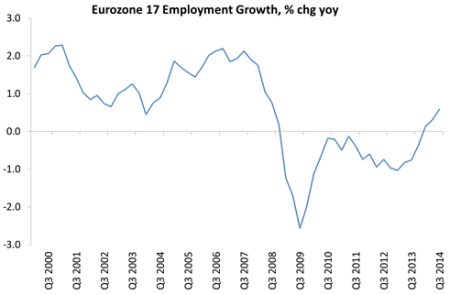

And finally there is some employment growth.

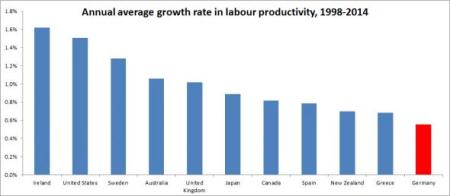

Indeed, the weaker Eurozone economies including Greece have lowered labour costs and closed down so many weaker companies that they are beginning to look competitive even with Germany.

Economies like Spain and Greece have actually had faster growth in productivity than in Germany because Spaniards and Greeks have worked longer hours.

Germany has still done better because its level of productivity is much higher anyway and it has been able to hold down wages (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/09/22/german-capitalism-a-success-story/).

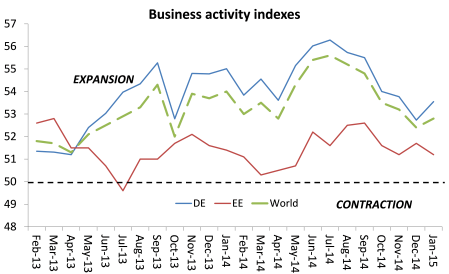

Business activity indexes have started to pick up in several Eurozone economies (although not yet in Greece). Indeed, this explains why there has been a slight rise in the business activity index for the major developed economies in the last month or so.

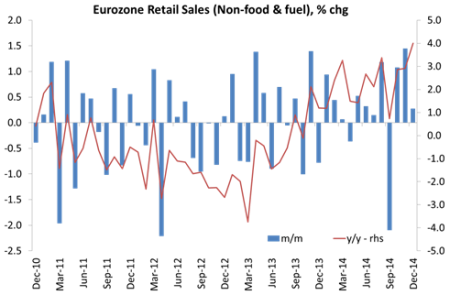

I have argued that the recent sharp fall in the oil prices leading to significant reductions in prices at the gas pumps and for energy is two-sided. It heralds a deflationary environment which is bad news for profitability. But it also means slightly more in the pockets of households to spend. And that is especially so in Europe, where oil prices are not an important source of growth and profit but are mainly a cost to households and businesses.

Retail sales in the shops in Europe have started to pick up, up by 2.8% yoy in December compared to just 1.6% yoy in November. Excluding spending on fuel, growth is even faster.

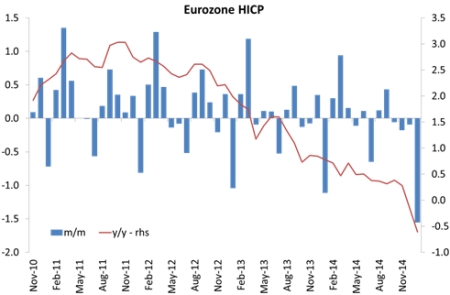

However, the risk of debt deflationary spiral remains, as the Eurozone remains in deflation.

If prices keep falling and growth does not return sufficiently, then the debt burden faced by both the public sector and the private sector in Eurozone economies will rise and there is a danger of a collapse of banking and corporate sectors.

A new report by McKinsey reckons that world capitalism has never been so awash with debt (McKinsey – Debt (Not Much) Deleveraging 040215. Global debt has increased by $57tn since 2007 to almost $200tn — far outpacing GDP growth. As a share of world GDP, debt has risen from 270% to 286%, despite the cleansing of the Great Recession. Capitalism is not out of the woods.

Overall, almost half of the increase in global debt since 2007 was in developing economies, but a third was the result of higher government debt levels in advanced economies. Households have also increased debt levels across economies — the most notable exceptions being crisis-hit countries such as Ireland and the US. China’s total debt, including the financial sector, has nearly quadrupled since 2007 to the equivalent of 282% of GDP.

The Monetarist wing of mainstream economics, as represented by Ben Bernanke, former head of the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England and now Mario Draghi at the ECB, reckon that when central bank interest rates are near zero (or even below as in Switzerland and Sweden), a good dose of money printing , or ‘quantitative easing’, can do the trick in getting an economy going. However, this has proved to be a chimera. Most of this extra credit or money has ended up in the stock and bond markets and in the cash reserves of the banks; very little has found its way to the so-called ‘real economy’ (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/11/02/the-story-of-qe-and-the-recovery/).

The Keynesian wing of the mainstream has argued that just printing more money is not enough: there must fiscal expansion i.e. government spending, to get capitalist economies out of their ‘secular stagnation’. The doyen of Keynesian economics, Paul Krugman, has demanded such spending and claims that increased government borrowing and debt is not a problem if it is just owed to others in the same economy or when economies are flat. Debt can be paid back later.

Simon Wren-Lewis, the UK counterpart of Krugman, has recently argued that the policy of fiscal austerity (government spending cuts and budget deficit reduction) pursued by the US, UK and European governments after 2010 was the main reason why the recovery after the Great Recession was slow in the major capitalist economies. In the US, real GDP growth was held back a full percentage point a year from 2010. More fiscal spending and all would have been well – it’s simples! (http://mainlymacro.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/post-recession-lessons.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+MainlyMacro+%28mainly+macro%29).

Such an argument is based yet again on the size of the spending ‘multiplier’. Wren-Lewis applies a multiplier of 1.5 – in other words for every 1% of GDP increase in government spending, there would be a 1.5% rise in real GDP. Actually, there is a big dispute about what the spending multiplier actually is, with some studies arguing for a multiplier of less than one. And then is the causal sequence: was austerity the product of the collapse in the real economy in 2009 or was the slow recovery a result of austerity? I have dealt with these Keynesian arguments and evidence in several posts.

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/10/17/the-dilemma-of-the-mainstream/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/10/14/the-smugness-multiplier/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/01/13/multiplying-multipliers/

For me, what G Carchedi and I call the Marxist multiplier is the most relevant driver of economic growth (https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/06/13/keynes-the-profits-equation-and-the-marxist-multiplier/.) What matters is whether profitability in the productive sectors of the capitalist economy rises or falls. From this will flow increased investment, employment and the ability to rise government spending. Increased government spending may boost consumer demand for a while, but at the expense of profitability. So it cannot last as a way out of crises.

In southern Europe, the worst hit part of advanced capitalism in this Long Depression, there are some signs that the bottom has been reached and recovery in profitability may soon begin. The problem is that in the other parts of the world economy, the risk of a new slump is increasing and is still necessary to cleanse dead capital and excessive debt.

But it is an irony that, as the Euro leaders and the ECB try to impose more fiscal austerity on Greece, there may just be a short window of opportunity for growth opening up for the Greek capitalist economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment