All the polls show that the leftist Syriza alliance is set to win the general election in Greece next Sunday. It may not get an outright majority and may have to form a coalition with one of the small centre parties. But it looks most likely that the incumbent coalition of Samaras’ conservative New Democracy and the degenerated social-democrat PASOK will lose power.

Financial markets are getting worried and Greek government bonds have dropped sharply in price as investors fear a default. Greek banks are losing deposits as Greek corporations and the rich (or at least those that have not already done so) shift their euros overseas. Three banks are now asking for what is called Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) from the Greek central bank (in effect, liquid funds from the Eurosystem controlled by the European Central Bank).

So what will happen if Syriza becomes the government next week? A guide to this was provided by a question and answer session with Syriza’s ‘shadow’ finance minister, Euclid Tsakalotos (soon to be finance minister?) at the London School of Economics that I attended this week. Tsakalotos is an Oxford university graduate, now at the University of Athens (http://uoa.academia.edu/EuclidTsakalotos).

The meeting was arranged by Professor Mary Kaldor at the LSE and Paul Mason, the Channel Four broadcaster (you can read his comments on the meeting on his blog, blogs.channel4.com/paul-mason-blog/Greece-syriza-election/2941).

Other attendees included some leftist think-tanks like the Jubilee debt campaign and Red Pepper. But also present were none other than Professor Chris Pissarides, the Cypriot-born economist at the LSE and a Nobel prize winner for economics for his work (see http://personal.lse.ac.uk/pissarid/). Pissarides announced that he was currently an economic adviser to Samaras!

Along with Pissarides was the former head of the Cyprus central bank and ECB council member, Panicos Demetriades. Demetriades was sacked by the Cypriot president after the bailout debacle there last year. He had been appointed by the previous Communist president and then was blamed by the Conservatives for the bank meltdown. But if he was a ‘liberal’, he did not show it at the meeting! His main line was that the ECB and the Euro leaders would not compromise on debt reduction and Syriza was living in cloud cuckoo land.

What was Tsakatolos’ position? He said that Greece had to get ‘fiscal space’. By this he meant that the government needed funds to spend on ending the humanitarian crisis, save health and public services and end desperate poverty. This could be done if the EU agreed to a debt reduction sufficient to reduce debt servicing to the minimum; and for the government to run a primary budget balance rather than a 4% surplus as the Troika (ECB, EU, IMF) demands.

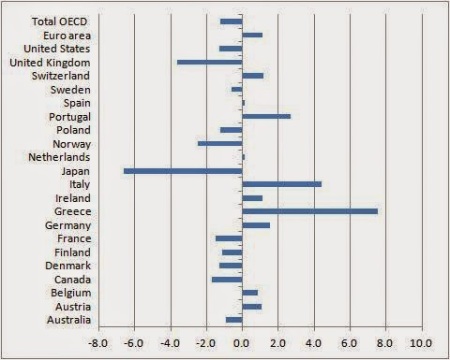

Tskatolos was clearly right in his priorities. The Greek economy remains in a parlous state. Unemployment was more than 25% at the last count. GDP has collapsed by more than 30% since its peak before the crisis: a decline comparable only to that seen in the US during the Great Depression. Public services have been decimated and poverty is rife, despite the resilience of the Greek people. The austerity measures demanded by the Troika for its loans and implemented by the coalition government with hardly a whimper has been draconian. A widely recognised measure of fiscal stance is the underlying (cyclically corrected) primary balance (the deficit less debt interest). It shows that Greek austerity has been huge.

If Greece got its ‘fiscal space’ then the Syriza government would have €6-7bn a year to spend.

The debt issue is clearly essential to deal with. Greece’s public sector debt to GDP ratio is at an astronomical 175% of GDP. Whereas the majority of that debt was held by French and German banks up to 2012, after the ‘orderly restructuring’ of the debt, now 78% of the Greece’s €317bn of public sector debt is held by the Troika.

As I have pointed out in previous posts, around 90% of the €217bn of loans provided by the Troika went to pay off Europe’s banks and the hedge funds that held the debt. The banks got most of their money back, leaving the Greek people with the bill. This is now owed to the Troika. Back in 2012, the EU leaders finally recognised that the huge public sector debt that the Greeks had incurred in bailing out their banks and in funding the repayment of debt and interest to foreign lenders (mainly German and French banks) was just too great. They agreed with the conservative government in Athens that more funds would be made available, but that private creditors would take a ‘haircut’ in what was owed them. So French and German creditors swapped their Greek government bonds for new ones worth a little less, but guaranteed by the euro stability funds (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/03/09/greece-the-biggest-debt-default-in-history/).

This ‘haircut’ (along with savage austerity measures) was designed to reduce Greek government debt from 165% then to 120% of GDP by the end of this decade. But the problem is that, if the Greek economy does not grow and drops into a deflationary spiral, then, even if the euro value of Greek debt is reduced, the euro value of Greek GDP will fall even more, so that the debt burden rises, not falls. And that is what has happened. Three years later, the Greek debt ratio is even higher at just under 175%.

The IMF continues to have the ludicrous position that this debt ratio can fall by 40 percentage points by 2019 – if austerity continues, as agreed by the conservative government with a primary budget surplus of 4% of GDP, if real GDP grows by over 3% a year and if inflation returns at a rate of over 1% a year. Instead the Greek economy is deflating. The debt ratio is likely to rise even more.

Tsakalotos reckoned that the EU leaders would agree to debt relief and an adjustment of the fiscal programme because it was sensible and had support in other parts of the Eurozone too. But the question of how to grow the Greek economy even if Syriza gets a debt deal with the EU, which remains in doubt, was not properly dealt with in his answers. Nobel prize winner Pissarides argued that the real task was to raise productivity through ‘labour market reforms’ along the lines of the Germans and now Italy’s social democrat PM Renzi. Pissarides meant by that ending restrictive practices in the trade unions; money for training instead of welfare benefits, privatisation etc. This openly neoliberal position was, of course, opposed by Tsakalotos.

Instead, Tsakalotos advocated a ‘social market’ model (apparently he is an advocate of the old ‘Alternative Economic Strategy’ in the UK promoted by the likes of Stuart Holland and other left reformists) where government intervenes to correct or help the capitalist sector. And he called for an investment programme using EU money from the EIB etc. But there was no mention of control of the Greek banks and strategic industries and we know that defence spending will be maintained and Syriza will not leave NATO (as Paul Mason pointed out).

Overall, my impression of Tsakalotos was his strategy was to put forward a ‘reasonable’ set of proposals to the Troika and hope/expect them to compromise on a debt deal. This was partly a hope and also tactical for the media.

What will happen? Can Syriza maintain what some have called the impossible triangle: namely 1) stay in power, 2) reverse austerity and 3) stay in the euro? Or will one or more have to go? Well, if Syriza does not get an outright majority, then debt negotiations will be weakened by a coalition government and there would be the possibility of a new election by the summer.

Probably the best that Syriza can expect is possibly some form of ‘London agreement’ (debt reduction along the lines that Germany got after the war) or more likely an extension of the terms of the debt with lower debt servicing costs or even perpetual rollover bonds. But this would have to be made available to the likes of Portugal and Ireland who otherwise may object that Greece is getting special treatment. But then the Germans could say, as they have already done, that Greece is an exception that proves the rule that the Eurozone works.

I still think the Germans do not want to push Greece out of the euro, despite the pressure of the eurosceptics in the AfD, as they see the risk of an involuntary exit with debt default as risky for the Euro project. So they may eventually offer some concessions (but probably way short of what Syriza needs).

The Breugel research think-tank has done some estimates of the likely losses that Germany would incur if there is a ‘Grexit’, i.e. Greece is forced out of the Eurozone. The Eurosceptic IFO Institute reckons that Grexit would cost Germany €76bn while a Greek default within the Eurozone would cost €78bn. Not much difference. But Breugel reckons that IFO has ignored the impact of losses for German corporations if there is Grexit and many Greek companies default on their trade debts. German banks and industry could take a big hit if Grexit happens (http://www.bruegel.org/nc/blog/detail/article/1542-why-a-grexit-is-more-costly-for-germany-than-a-default-inside-the-euro-area/).

The negotiations on the debt are likely to be tortuous and so I expect the EU leaders/ECB to keep the Greek banks and government afloat over the next few months. I doubt there will be a run on the banks or a collapse of Greek banks. It is too dangerous for the Eurozone as a whole for the ECB to allow it.

Then the question is posed to Syriza: do they accept less than acceptable debt terms and hope to use the time to grow the economy on a capitalist basis; or do they reject them and opt Argentina-style for a unilateral debt reduction and budget spending? The latter option would mean possible EU loan suspension and ECB lending (although that would be illegal under EU rules). Then Syriza would have to take over the banks and leading industries, involve workers in production control; slash defence spending and monies for the army and police; and appeal for EU support for an EU-wide growth plan based on public investment.

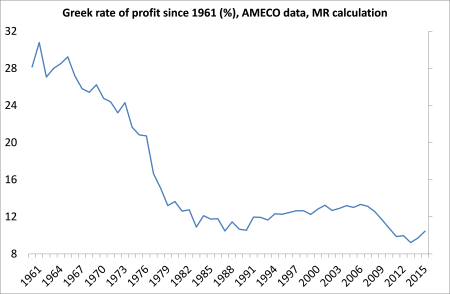

I think a compromise deal is most likely; giving Syriza some time to hope for recovery on a capitalist basis. What are the chances of that working? Well, Greek labour costs have been slashed so Greek capitalism is more ‘competitive’ …

but the private sector is not investing and profitability is very low.

The EU will likely inject some EU funds into Greece but not €6-7bn a year as Syriza hopes – and even that is nothing after the 40% cut since 2009. So over time, the pressure will build from below for more serious action to end poverty, create jobs and restore public services, particularly education, housing and health.

If Syriza cannot or won’t respond to that pressure, then it will split or its supporters will become disillusioned and Syriza will fall back. Syriza is divided between those like Tsakalotos who look for a ‘social market’ solution within the Eurozone and those like Costas Lapavitsas who reckons the only answer is for Greece to leave the Eurozone. Lapavitsas is a professor at London University most noted for his work on financialisation in modern capitalist economies (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/11/12/the-informal-empire-finance-and-the-mono-cause-of-the-anglo-saxons/). Now he is standing as an MP for Syriza.

And he is not the only leftist/Marxist economist doing so. It seems that Syriza has more UK or US-trained economics professors on their MP list than any party in Europe!

Another on the Syriza list is Yanis Varoufakis, professor of economic theory at the University of Athens, who has been calling for a Europe-wide, EIB backed investment programme to revive the Eurozone economy (http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/). He has had misgivings about being a candidate for parliament as he is not sure ‘the triangle’ is possible (http://www.bostonreview.net/world/varoufakis-greece-austerity-syriza-left). During the Cypriot banking crisis and bailout last April, he advocated selling back the recapitalised banks to the private sector

(https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/04/20/why-sell-back-the-viable-banks/).

Public ownership of the banks and strategic industries should be a central part of Syriza’s programme for economic revival, but it is not.

The ‘impossible’ triangle for Syriza of staying in power, reversing austerity and keeping the euro remains a question mark. But no crisis of policy and action is likely in months as some at the LSE seminar seemed to think. I think we could be discussing the same dilemmas on debt, growth and the EU this time next year.

No comments:

Post a Comment