2014 was supposed to be the year that American troops left Iraq, having completed their task of establishing a pro-West democratic government there. It was also the year that British troops left Afghanistan, having completed their task of ‘pacifying’ the notoriously wild Helmand province, leaving the Afghan army to control the region on behalf of the pro-West democratic government based in Kabul.

The reality, of course, is a sorry joke. Both armies, far from leaving the war arena, are now engaged in ‘supporting’ air strikes and a Kurdish army in a battle against a new Hydra head in the shape of ISIS in Syria and Iraq, while Taliban continues its horrendous battle against American and Pakistan forces (and their drones) in the hills of Afghanistan and against the people in its towns. The wars are far from over and these attempts to impose imperialist control over a multitude of forces are failing, just as the Roman armies failed to subdue the Germanic and other tribes along its northern reaches back some 2000 years ago onwards. The cost to the Roman state was ruinous and eventually too much to cope with.

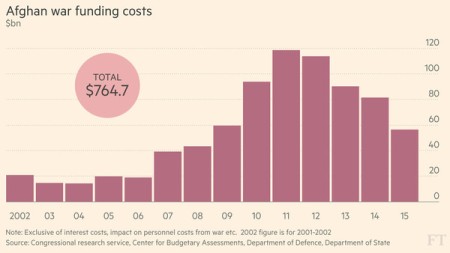

The cost to the US and its allies in the ‘coalition of the willing’ is also huge, if still possible to absorb. According to the latest estimates, the Afghan conflict has cost $1trn so far since 2002. That’s only about 0.6% of US GDP a year – but not something to ignore, given the low growth in the economy since 2008 and the alternative ways that money could have been spent on to preserve public services or boost the productive sectors of the economy.

According to John Sopko, the US government’s special inspector-general for Afghanistan, the amount the US has spent on reconstruction in Afghanistan when adjusted for inflation is more than the cost of the Marshall Plan to rebuild western Europe after 1945 – and for no result. The waste has been immense too. $500m was spent on 16 transport planes for the Afghan Air Force. The fleet was stored in Kabul for year and the planes were turned into $32,000 worth of scrap metal. Another $34m was spent on a base in south-western Afghanistan. It came equipped with a 64,000 sq ft operations centre and briefing theatre, and has never been used. $3m on eight patrol boats for Afghan police, still in Virginia storage after four years; $5.4m incinerators, installed incorrectly, never used; $3.6m on TV broadcast trucks for live sporting events, unused in Kabul storage – and so on.

To this bill must be added the Iraq war, which has cost $1.7tn, according to the Costs of War Project by the Watson Institute for International Studies at Brown University. And there will be an additional $490bn in benefits owed to war veterans, expenses that could grow to more than $6trn over the next four decades, counting interest. According to Ryan Edwards at City University of New York, the US has already paid interest of $260bn on that war debt.

The war in Iraq has killed at least 134,000 Iraqi civilians and may have contributed to the deaths of as many as four times that number. When security forces, insurgents, journalists and humanitarian workers were included, the war’s death toll rose to an estimated 189,000, the Watson study said. Then there are medical costs already incurred for soldiers who have left the military. Linda Bilmes, a Harvard economist who has done extensive research on the war costs, estimates that medical spending on veterans from both Iraq and Afghanistan has so far reached $134bn. Military healthcare premiums paid by serving military members have been kept low, prompting a surge in healthcare spending by the Pentagon, while salaries have risen above inflation. Since 2001, the defence department’s base budget has increased by $1.3trn more than its own pre-9/11 forecasts.

And the spending is not over.

The Pentagon has indicated it wants further funding of $120bn for 2016-19 for operations in Afghanistan. US troops numbering 10,000 are to stay in Afghanistan for at least the next two years at an estimated $7bn a year. Prof Bilmes forecasts future medical and disability costs for veterans from both Iraq and Afghanistan will reach $836bn over the coming decades. The two wars have also added to the Pentagon’s fast-growing pension bill: the military pension system has an unfunded liability of $1.27trn, which is expected to rise to $2.72trn by 2034.

This disaster, both in human terms and in money, is repeated on a smaller scale with the British military intervention. British troops are home from a campaign that lasted 13 years, including Iraq in the middle. PM David Cameron announced in December 2013 that the troops could come home because their ‘mission had been accomplished’. A new book by Frank Ledwidge (Investment in Blood: The True Cost of Britain’s Afghan War) tallies the personal and financial cost of Britain’s Helmand campaign, pointing out that Britain’s failure has “obliterated any consideration of dead Afghans and folded the British war dead into a single mass of noble hero-martyrs stretching from 1914 to now” with the display of plastic red poppies at the Tower of London. See my previous post on Ledwidge’s work at

http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/06/01/dont-mention-the-war/.

Ledwidge estimates British troops alone were directly responsible for the deaths of at least five hundred Afghan civilians and the injury of thousands more. Tens of thousands fled their homes. ‘Of all the thousands of civilians and combatants,’ Ledwidge writes, ‘not a single al-Qaida operative or “international terrorist’” who could conceivably have threatened the United Kingdom is recorded as having been killed by Nato forces in Helmand.’ Since 2001, 453 British forces personnel have been killed in Afghanistan and more than 2600 wounded; 247 British soldiers have had limbs amputated. Unknown numbers have psychological injuries.

The British operation in Helmand alone cost £40bn, or £2000 for each taxpaying British household! Britain built a base in Helmand, Camp Bastion, bigger than any it had constructed since the end of the Second World War. It has now handed Camp Bastion over to the Afghan military which is now struggling to prevent it being overrun by attackers. Everything the military did depended on the petrol, diesel and kerosene trucked in from Central Asia or Pakistan; one US estimate calculated that the price of fuel increased by 14,000% in its journey from the refinery to the Afghan front line. In firefights, British troops used Javelin missiles costing £70,000 each to destroy houses made of mud. In December 2013, when they were packing up to leave, they had so much unused ammunition to destroy that they came close to running out of explosives to blow it up with.

Ledwidge adds in the cost of buying four huge American transport planes to shore up the air bridge between Afghanistan and the UK (£800m), 14 new helicopters (£1bn), a delay in previously planned cuts in the size of the army (£3bn) and the cost of returning and restoring war-battered units (£2bn). And £2.1bn spent on ‘aid and development’, most of which was stolen or wasted. Grotesque sums were spent on providing security and creature comforts to foreign consultants: an annual cost of around £0.5m per head!

Ledwidge estimates the cost of the British military’s bloodshed and psychological trauma – the amount spent on the ongoing treatment of damaged veterans, compensation under the recently introduced Armed Forces Compensation Scheme (AFCS), and an actuarial estimate of the financial value of human life – at £3.8bn. An Afghan who sought compensation from the British in Helmand after losing his sight as a result of a military operation might expect a payment of £4500. A British soldier suffering the same injury would be entitled to £570,000.

The whole British campaign in Helmand was a failure: ‘The Afghan army in Helmand was non-existent. The local Afghan police were, on the whole, criminal. The Helmand director of education was illiterate. The British were never fighting waves of Taliban coming over the border from Pakistan: they were overwhelmingly fighting local men led by local barons who felt shut out by the British and their friends in ‘government’ and sought an alternative patron. The Taliban provided money, via their sponsors in the Gulf, and a ready-made, Pashtun-friendly ideological framework the barons could franchise. Since the British were hated even before they arrived, recruitment of foot soldiers was easy.” (An Intimate War: An Oral History of the Helmand Conflict 1978-2012 by Mike Martin).

So after 13 years of war in far-flung places, American and British imperialism have nothing to show for it, while hundreds of thousands of Iraqis, Afghans and Pakistanis have been killed, injured, tortured and made homeless. And American and British taxpayers have seen their public services cut and their taxes go to fund extravagant, wasteful and hopelessly failed wars to preserve corrupt, unpopular elites in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf states and to sustain the interests of the multinational energy companies.

No comments:

Post a Comment