Making predictions or forecasts about a national or the world economy is fraught with failure. There are so many variables to consider and the data available are often inadequate and biased. But the main reason why economists are usually wrong with their forecasts and predictions is that mainstream economics has no real theory or laws of economics to build predictions on. Nevertheless, they carry on making them, either as an act of hubris (we are so clever!) or because their bosses and clients in investment banks demand it.

No wonder professional economists have predicted none of the last seven recessions. Mainstream economists, being an apologia for the success of market economies and capitalism, never predict a recession, even when one is staring them in the face, as it did at the beginning of 2008. Indeed, since 2001, only an average 12.7% of economists surveyed by James Montier from GMO were right about the following year’s economic growth.

Anyway, I shall try and make some predictions and forecasts for 2015. And at least my forecasts are based, I think, on relying on some important underlying laws of motion of capitalism. That should make my forecast a touch more accurate – I think. Economists, if they are serious about making a science of political economy (perhaps a contradiction in terms!), must make predictions as part of any test of laws, as in natural sciences. It is not good enough for Marxist economists just to say, well, ‘under capitalism there will be recurrent crises (slumps)’. We have to do better than that: namely, at what stage is capitalism going through; is it on an upswing or downswing; is a slump close to hand or some way away?

Back in 2005, when I wrote much of my book, The Great Recession (published in November 2009), I forecast that a major slump was likely to take place in 2009-10. This is what I said: “There has not been such a coincidence of cycles since 1991. And this time (unlike 1991), it will be accompanied by the downwave in profitability within the downwave in Kondratiev prices cycle. It is all at the bottom of the hill in 2009-2010! That suggests we can expect a very severe economic slump of a degree not seen since 1980-2 or more”.

As the quote suggests, I based this forecast or prediction on some laws of motion in capitalism that I had identified. The first was the long cycle in global production prices, namely a period of 27-36 years of general upswing in commodity and production trade prices, followed by a similar downswing. This is called the Kondratiev wave. I reckoned that since 1982, the Kondratiev cycle was in a downswing that could last until 2018. This would keep inflation low and indeed deflation of prices would appear, placing downward pressure on global investment.

The second was that the domestic construction or property cycle (of about 18 years) in major economies like the US and the UK was reaching its peak and we could expect a housing bust around 2009.

Third, and most important, I had discerned that there was profit cycle that could be identified for the major capitalist economies over about 32-36 years from trough to trough. From the late 1990s, most capitalist economies were experiencing a downwave in the profitability of capital that was only being propped up by a credit boom and fictitious capital profits. The downwave would come to a new trough about 2015-16. And in such a downwave, more frequent and deep recessions were likely, as they had been in the previous downwave of 1965-82: with a weak one in 1969-70; a major international one in 1974-5 and finally the double-dip slump of 1980-2. This created the conditions for a revival in profitability (the so-called neoliberal period) that lasted until the end of the century. Back in 2005-6, I reckoned the profit downwave signalled at least another huge slump.

Finally, there was the Juglar cycle of growth, investment and employment which seemed to last about 8-9 years from recession to recession in modern economies. These recessions took place in profitability upswings, but then they were weak and scarce (1958 or 1990). In downswings, they were more frequent and severe (1929-32, 1937-8 or 1974-5, 1980-2).

On that basis, I reckoned that all these cycles would come together in a major slump around 2009-10, as we had not had all four cycles in a downswing together before since the 1930. Well, I was slightly wrong: the credit bubble burst in 2007 and the Great Recession came one year earlier than I predicted, in 2008-9.

As we enter 2015, both the Kondratiev and profitability cycles are still in a downwave, in my opinion, but the construction cycle has turned up (in some cases leading the current weak ‘recovery’). But another slump must still be on the agenda to enable sufficient destruction of capital values to deliver a new upwave in profitability and also see the end of Kondratiev downwave. If you like, the major economies are halfway through a Long Depression, as in the 1880-1890s or the 1930s. The 1974 slump was eventually followed with the 1980-2 slump; the 1929-32 slump was followed by a recovery and then another slump in 1937-8. So on that basis, after the recovery of 2009-14, we can expect another slump by around 2016-17. There – I have said it now.

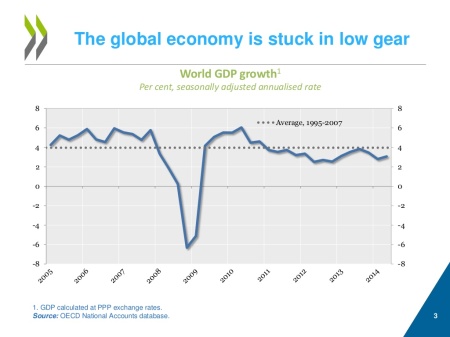

But what of 2015? Well let’s start by reminding myself of what I said this time last year about 2014 (http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/12/30/faster-growth-in-2014/). My general forecast for 2014 was that, contrary to the optimism of the professional mainstream economists working for big money at the likes of Goldman Sachs, the ‘global crawl’ would continue i.e. global economic growth would continue to be weak and below average as it had been ever since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. And so it has proved.

Back at the beginning of 2014, the IMF forecast a 3.6% expansion in real GDP in the world economy. It will come in at just over 3%, well below the average. The rich investment bankers at Deutsche Bank and Goldman Sachs reckoned that the US economy would grow “above-trend” in 2014. Well, it’s true that the US had a good third quarter of growth, being the best performing capitalist economy since the end of the Great Recession (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/12/24/us-economy-ends-on-a-high-the-uk-le), but it will still achieve only about 2.5% growth, at best, in 2014, well below average trend growth of 3.3% since the 1980s.

As for the UK, I reported last year that the Conservative-led government’s finance minister, George Osborne, was being lauded as a hero because the UK economy would jump ahead in 2014. And indeed, up until the latest data on growth, it seemed that the UK would achieve the fastest expansion of the top G7 capitalist economies in 2014, at 3%. However, such hopes have now been dashed and the UK economy will only manage about 2.5-2.7% this year.

Even this growth has been based on government stimulus for house-building and cheap credit. Investment in productive sectors has been weak. Real GDP per person is still below the peak achieved in 2008 before the Great Recession. Investment in real terms is still 4% below, manufacturing output 5% below and productivity per hour still over 1% below its peak before the Great Recession. Britain is running a payments deficit with the rest of the world equivalent to 6% of GDP, bigger than the government deficit. Above all, net national disposable income per head (after inflation) is some 6% below the peak and real weekly earnings have fallen since the Tories took office in May 2010 in every quarter but two – the longest fall in real wages since the Great Depression.

And it does not look any better in 2015. The housing boom in the UK is beginning to fade and will expose the underlying weakness in the productive sectors in 2015. Average house prices are rising at their slowest rate for more than a year. And according to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), UK wage growth is likely to remain weak for at least another year because employers are finding it easy to recruit and retain staff at current pay levels. Employers surveyed in the autumn had an average of 50 applicants for every low-skilled vacancy and 20 for every high-skilled vacancy, 40 per cent of whom were suitable for the role. They also reported that job turnover remained low. “If few employees are leaving, and most employers can find suitable applicants for vacancies, the conditions required for higher across-the-board pay rises are not being met,” said Mark Beatson, CIPD’s chief economist.

Indeed, that is the story for most capitalist economies in 2014 (Europe, Japan, the US and the UK): weak economic growth, poor business investment and falling real incomes for the average household.

Last year I forecast a very weak Japanese economy and it has proved to be even worse that I forecast, despite dollops of virtually interest-free credit, fiscal stimulus packages and another election to install Abenomics – the supposed answer to Japan’s woes (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/10/13/japan-the-failure-of-abenomics/).

And lo and behold, as I write this, the Bank of Japan’s own economic activity survey, the Tankan, suggests that “Japan is going into a double dip”, recession with only a small quarterly increase in GDP for the final quarter of 2014 followed by a renewed contraction next year. In the survey, large Japanese companies gave a score of 14 for current business conditions and forecast a decline to 12 in three months’ time. For small companies, the respective figures were 0 and -4.

The Abe government has launched yet another round of fiscal stimulus measures. It’s going to cut corporate tax rates to try and encourage Japanese companies to invest more and raise wages for their workers and so boost demand. Some hope! Large companies have instead been building up their cash reserves and keeping wages down.

And all this extra spending threatens the other major policy of Abenomics – to get Japan’s huge public sector debt and deficits down. The debt has not been a problem up to now because the interest rate on that debt is near zero and Japan’s banks are pressured to buy government bonds. But this means that little productive investment takes place and if interest rates were to rise, Japan could face a serious debt crisis. The government wanted to reduce its annual deficit by half in 2015 and ‘balance the books’ by the end of the decade. But the economy has been so weak that it has been forced to hold back an increase in sales tax, spend $28bn on projects and give new handouts to corporations. The fiscal target is a joke. What is down the road will be a severe cut in welfare and social benefits to pay for this.

As for Europe, there is no relief. Greece may have finally bottomed the deepest slump in its modern history in 2014, but only after a 40% fall in average living standards and the destruction of jobs, welfare, health and public services. Now it is about to enter a major battle with the EU leaders over how to recover (see below). Spain is still recording record high unemployment levels and with little sign that the productive sectors of the economy are turning up; Italy remains in a depressed state. Only the German economy looks relatively better.

The global economy remains in a crawl and will do so in 2015 for one good reason: the failure of business investment to leap forward. Goldman Sachs reckoned this time last year that there would be a global investment boom in 2014. That has proved to be a mirage in Europe, Japan, the UK and in the major so-called emerging economies of China, India, Brazil and Russia, where investment growth has slowed markedly or collapsed, as in the case of Russia (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/12/08/oil-the-rouble-and-the-spectre-of-deflation/). The emerging markets of Brazil, Russia, India and China collectively known as the BRICs — will likely grow in 2015 at their slowest pace in six years, according to Oxford Economics. Only the US has shown some pick-up in investment.

As I said last year, the reason that business investment has not boomed is that in most economies average profitability remains below levels before the Great Recession and below levels reached in the late 1990s. Most economies are still experiencing the downwave in the profitability cycle, as explained above. Coupled with the downwave in the Kondratiev cycle, that is why the global capitalist economy is in what I call a Long Depression, with some years to run.

Let’s finish with a few predictions.

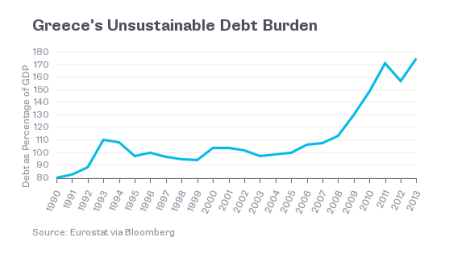

First, the failure of the Samaras government to get its candidate for President elected by the Greek parliament has forced an election at the end of January that the leftist Syriza party is likely to win, assuming the public opinion polls remain as they are. Syriza will likely have to form a coalition with smaller left and centrist parties. It is pledged to renegotiate the debt burden that the previous government has built up with the EU, some €322bn. This can never be paid off and remains a millstone around the neck of the Greek economy and its people for decades.

Syriza wants much of it written off. The EU leaders will play hardball, if only because it is making Ireland and Portugal pay their loans back in spades and it won’t want to set a precedent for other Euro debtors. The existing Troika programme funds are supposed to fund the Greek government from February as long as the government agrees to more fiscal austerity. Syriza claims it will do no such thing, so there appears to an impasse with Greece running out of cash by the summer.

I reckon that this process will spin out through the next few months with nothing resolved. There is a way out for the EU leaders if they want to keep Greece in the euro: they could eventually agree to a perpetual rollover of the debt – so the debt stays on Greek books but there’s nothing to pay for the foreseeable future. This could be sold as the ‘Greek exception’. Alternatively, Syriza reaches a compromise agreement to cover the debt. Either way, my prediction is that Greece will still be in the Eurozone this time next year.

What’s going to be interesting in 2015 is the number of elections in key peripheral Eurozone states coming up. Apart from Greece, Ireland and probably Italy will have elections, where weak centrist governments will try to ‘hold the line’ against populist parties. I will consider the economic programmes of leftist parties like Syriza and Podemos in future posts.

And then there is the UK with a general election in May. I have made three predictions about the UK in the past. The first was that Scotland would vote to stay in the United Kingdom in the referendum last September (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/09/19/scotland-one-prediction-right). That happened. The second was that the Conservative-led coalition would be returned to office (probably the Liberals in tow again). And the third was that the British people would vote to stay in the EU if there is referendum on that in 2017. I’ll explain my prediction for the May election in a post nearer the date.

For 2015, I have launched a Facebook site so that you can keep up to date with my posts and other events and papers. See

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Michael-Roberts-blog/925340197491022

and

Createspace https://www.createspace.com/5078983

or Kindle version for US:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00RES373S

and UK

http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/?field-keywords=Essays%20on%20inequality%20%28Essays%20on%20modern%20economies%20Book%201%29&node=341677031.

No comments:

Post a Comment