Speaking at the close of the G20 summit of world leaders in Brisbane Australia, British Prime Minister David Cameron exclaimed that “red warning lights are flashing on the dashboard of the global economy”, threatening another recession.

Of course, Cameron was not talking about the UK economy, which is going great guns, according to the British government, with six months to go a general election. Instead, he was covering his back, so that if any downturn in the British economy took place it could be blamed on the rest of the world. You see, as Cameron put it in an article for the Guardian, don’t blame me, you lefty liberals. If things go wrong from here, it will be because of the Eurozone that you all like so much. “The Eurozone is teetering on the brink of a possible third recession, with high unemployment, falling growth and the real risk of falling prices too.”

But he had to admit also that “emerging market economies which were the driver of growth in the early stages of the recovery are now slowing down. Despite the progress in Bali, global trade talks have stalled while the epidemic of Ebola, conflict in the Middle East and Russia’s illegal actions in Ukraine are all adding a dangerous backdrop of instability and uncertainty.”

In effect, Cameron was accepting that capitalism is now global and no one country can escape if there is a crisis or slump in another large one or neighbour. If the Eurozone stays in depression and other major economies in the G20 also slip back into a slump, the UK economy will join them.

The G20 leaders announced that they were pledging to boost real GDP growth in the world economy by an extra $2trn, or a cumulative 2%, by 2018. This pledge was full of holes. First, growth is expected to be very weak over the next four years, at least compared to the rate of world growth before the Great Recession (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/11/08/the-world-economy-in-low-gear/). So an extra 2% cumulative, or about 0.4% a year, would still mean slower growth than the global average in the last 20 years. Second, this was just a pledge: none of the G20 leaders were committed to implementing any of the measures necessary to achieve it.

The main method for doing this was to increase infrastructure investment (i.e more roads, railways, bridges, dams, broadband and other key long-term projects). A “Global Infrastructure Hub” is to be set up to promote more spending to close what is calculated as $70trn gap in such investment, or 100% of world GDP.

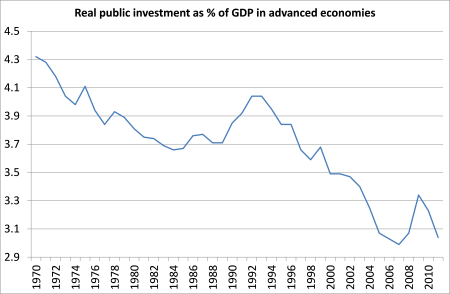

Again, this is likely to be pie in the sky. Throughout the neoliberal period (1980-2007), public investment has been viewed as a dirty word. So it has been systematically cut back.

Now the IMF has been calling for action to boost infrastructure spending in its reports for the last year. But when you read the data on this, you find that the main method for the very necessary ‘austerity’ programs made by the governments of the leading economies to manage the extra borrowing and debt built up from bailing out the banks and the loss of income from the Great Recession was by cutting infrastructure spending! Most of such spending is financed by public investment as private capitalist companies are reluctant to fund such long-term risky projects unless backed by governments (the taxpayers). And it is public investment that has been slashed as the first way of getting government spending down (followed by cuts in welfare spending).

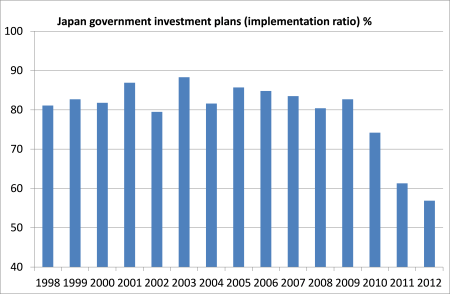

Take Japan. In order to try and control its government spending and get its large budget deficit down, the government just stopped its investment programs for the country.

Talking of Japan, as Cameron warned the world of a possible new global slump, we got the shock news that the Japanese economy had contracted by another 0.4% in the third quarter of this year and was thus technically in a new economic recession, while the fall in Q2 was revised down further. This was a shock for the mainstream economic forecasters, who had expected an expansion, although some of us had seen it coming (see my post http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/10/13/japan-the-failure-of-abenomics/).

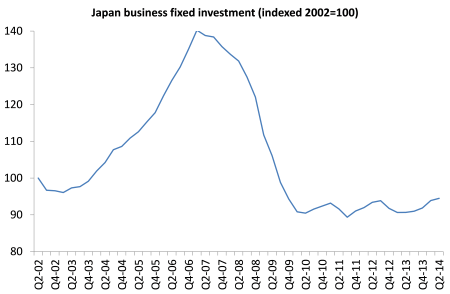

It seems that the huge jump in sales tax imposed by the Abe government as part of its ‘three arrows’ of reform has driven real incomes for average Japanese households down so much that they have stopped spending. Private consumption is down since April at an annual rate of 10%, buying homes is down even more and most worrying for growth, business investment fell. And we have seen above that government investment has also been cut.

The Abe government now look set to delay its proposed second round of sales tax increase and probably call an early election so that the government can get a suitably long time to impose further measures on the population.

Paul Krugman has piped up in his blog to argue that it was good news that Abe was going to delay the sale tax hike – indeed he should drop it altogether (http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/11/16/japan-through-the-looking-glass/). Krugman reckons that the Japanese economy is in a typical Keynesian liquidity trap and with interest rates ‘zero bound’ more quantitative easing won’t be enough to get the economy out of dreaded deflation. What was needed was “a credible promise to be irresponsible”. The government should spend more and not worry about the budget deficit and the government’s debt level. More spending will boost growth and inflation and the deficits and debt will then look after themselves.

Krugman did not tell his readers that just a few years ago he reckoned that more monetary easing and fiscal spending would get Japan out of its hole, when this blog argued that it would not. Who was right? (http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/02/14/japans-lost-decades-unpacked-and-repacked/).

As it is, Japan has been running huge budget deficits to try and boost the economy and has not imposed any serious measures of austerity. According the IMF, Japan’s government deficit stood at 7.1% of GDP in 2014, nearly double the OECD average. Japan has reduced its deficit by 30% since the peak of the Great Recession in 2009. But the OECD average reduction is 60%. If we exclude the effects of the cyclical recovery since 2009 on government revenues and spending, then Japan’s austerity program has cut the deficit by 15%, but the OECD austerity average is 60% and Greece’s is over 100%!

What is holding back the Japanese economy is not a lack of government spending or more credit but the unwillingness of the capitalist sector to invest.

The Abe government has made huge efforts to get the profitability of Japanese capital back to pre-crash levels. And by reducing real wages, it has succeeded somewhat. But not yet enough it seems.

This is the common story of the weak recovery. The share of new value going to labour has been squeezed through unemployment, low wage jobs that are temporary, casual or part-time, along with cuts in welfare, pensions and higher taxes. So the share of new value going to profit has rocketed. But not enough to get kick-start capitalist investment. So, while Cameron turns the red warning lights on, the IMF now calls for government investment, while governments try to keep spending down. It’s a funny old mess.

No comments:

Post a Comment