by Michael Roberts

This week the 5th plenum of the Chinese Communist Party

central committee is taking place. The plenum is to discuss the

progress of the Chinese economy and to decide on real GDP growth and

other targets for the new 2021-25 five-year economic plan for China.

The plenum will also discuss a broad plan for the next 15 years, with

goals that are likely to endure for at least the rest of 67-year-old

President Xi Jinping’s rule. This year’s meeting comes as the deadline

for meeting the previous overarching goal of achieving a “moderately

prosperous society”, is due to expire in 2021, the centenary of the

founding of the Chinese Communist party.

Beijing has hinted it would broaden out its focus on economic growth to include targets for environmental protection, innovation and self-sufficient development — such as in food, energy, and in chips. This is all part of the strategy of developing a “dual circulation” economy in which China will develop domestic demand and self-sufficiency while the rest of the world remains stalled by coronavirus.

Beijing has set an average annual GDP growth-rate target in every Five-Year Plan since 1986. But this year, as the economy was pummelled by the Covid-19 pandemic, China for the first time did not define a target. The new GDP target is likely to be lowered from the 6.5% a year set in the current plan to 5% or so in the next.

There is much to discuss about China: how it dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic and how quickly it is recovering economically. Then there is how the ‘cold war’ between China and the US will pan out and what it means for the world economy. And perhaps most important of all: will China be able to continue to grow at a fast-enough pace to reduce poverty and raise living standards as it has done so successfully over the last 40 years. I shall come back to these questions in future posts, but in this post, I want to discuss China’s growth, as measured by the mainstream economics measure, gross domestic product (GDP).

The reason for doing that is because the official statistics for China’s GDP and its annual growth since the 1949 revolution have been disputed by ‘Western’ economists and even Chinese ones. The dispute ranges from just arguing that the Chinese authorities just blatantly lie and make their figures up to a more reasoned view that official calculations are faulty. That China just makes up its figures has been pretty conclusively rejected by those who have studied them closely. “The findings are that the supposed evidence for GDP data falsification is not compelling, that the National Bureau of Statistics has much institutional scope for falsifying GDP data, and that certain manipulations of nominal and real data would be virtually undetectable. Official GDP data, however, exhibit few statistical anomalies and the National Bureau of Statistics thus either makes no significant use of its scope to falsify data, or is aware of statistical data regularities when it falsifies data.”

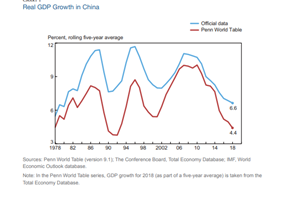

However, there is a large body of analysis that argues that conceptual and statistical frailties in China’s statistical work has led to an exaggeration of China’s real GDP growth since the 1949 revolution and especially since the ‘market reform’ period initiated by Deng started after 1978. The main source of this view comes the US Conference Board, a mine of statistical information on the GDP, GDP per head, productivity and employment for most countries of the world. The Conference Board has adjusted China’s real GDP growth rate going back to the 1950s to produce a much lower rate of growth than the official data.

The CB finds that, while the official data reckon that real GDP growth in China from 1949 to 2019 was 8.5% a year, it was really only 5.9% a year, some 30% slower. The gap is even greater in the post-Mao period up to 2000, with China’s official real GDP growing at 9.7% a year while the CB finds it grew at 6.3% a year or 35% slower. After that, the gap between the two measures narrows somewhat. With real GDP per capita growth (taking into account population growth), the gap between the official data and the CB data is even greater.

| GDP growth | 1953-19 | 1953-78 | 1979-2000 | 00-19 | 08-19 |

| Official | 8.5 | 6.7 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 8.5 |

| CB | 5.9 | 4.4 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 6.0 |

| GDP per capita growth | |||||

| 1953-19 | 1953-78 | 1979-2000 | 00-19 | 08-19 | |

| Official | 7.1 | 4.5 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 8.0 |

| CB | 4.5 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 5.5 |

How does the CB reach different results from the official data? The CB bases its results on the work of Harry Wu from the Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo. Wu has worked with the great world growth economist, Angus Maddison and is the adviser to the CB on China’s stats. Wu finds conceptual and technical flaws in the official data which when adjusted produce much lower growth rates in productivity and thus in GDP and GDP per capita.

There are many faults that Wu claims to find in the official data, but there are two that deliver the largest reduction to the official growth rate. One is conceptual and one is technical. The first conceptual one is that the Chinese stats exclude any ‘non-material services’. These are financial services, business consultancy, real estate agencies etc – in other words, non-productive services. This was done in China from the beginning so that GDP reflected more the productive sectors of the economy. Of course, this is anathema to mainstream economics based on GDP conceived by Simon Kuznets to measure the progress of a capitalist economy. When Wu adds in his own estimates of these sectors to China’s GDP, this raises the total value of GDP and leads to a different scale of growth. It knocks off from China’s official growth rate 0.4% pts a year for the Mao period and 0.7% pts a year for the post-Mao period.

The second main adjustment is to the prices of produced goods. Many goods disappear over time and are replaced by new goods with different prices. So the value of the basket of goods in GDP will change accordingly. Wu adjusts GDP according to his own calculations for this, which knocks off another 1.7% pts a year in the post-Mao period. These two adjustments account for most of the difference between the official growth figures and the CB ones.

I think there is much to dispute with Wu’s adjustments. First, the official stats provide a better guide to the strength of the key productive sectors of the economy than the mainstream GDP data. Second, the Wu commodity price adjustments seem arbitrary and open to dispute. Wu’s adjustments lead not only to significantly different results for GDP growth but also to productivity growth, and to that neoclassical measure of ‘innovation’, total factor productivity (TFP).

As Wu concludes: “We have confined the present study to the well-known neoclassical growth accounting framework adopted in most of the existing studies, explicitly or implicitly. As stated at the beginning of the paper, the purpose of this study is to discover how and to what extent data problems may affect the estimated TFP growth, rather than building up a new theoretical framework to explain China’s TFP performance. For this purpose, I have maintained the same approach and the same theoretical framework. Nevertheless, it is perfectly reasonable to argue that the neoclassical framework used in this study is questionable.”

Nevertheless, Wu’s adjustments to the official GDP growth rates for China have become widely accepted. The Penn World Tables, a major database for much world economy analysis, now uses the CB estimates for China’s real GDP. So let us accept for now, the CB adjusted data for Chinese economic growth. What does it mean in gauging the past success of the Chinese economy and the likely projection for GDP, productivity and investment growth ahead?

The New York Federal Reserve has published just this week a brand, new in-depth analysis of Chinese economics growth using the Penn World Tables (and thus the CB estimates). According to the NY Fed, Chinese real GDP growth has averaged 6.9% since 1978, more than 2 percentage points below the official figure. The estimated overstatement of growth varies considerably over time, from more than 3 percentage points for much of the 1990s to less than 1 percentage point until recently. So the Wu adjustment effect is disappearing.

But even if you accept the lower rate of growth, as the NY Fed says “China’s growth performance remains remarkable. For our sample of 124 economies, China has come in above the 90th percentile of the global growth distribution more than half the time since 1982, and above the 75th percentile until just last year. China’s growth over the past 20 years (7.5 percent) somewhat lags that of the high-income Pacific Rim during the periods in which they rose to China’s current per capita income level, but stands in the middle of the pack in per capita terms (6.9 percent).” And what the Fed does not mention is that China is a giant compared to the city states of Singapore and Hong Kong and is also immensely larger in GDP and population than Taiwan, Korea and even Japan. To achieve high annual growth in such a large economy in the last two decades to 2018 is truly historic.

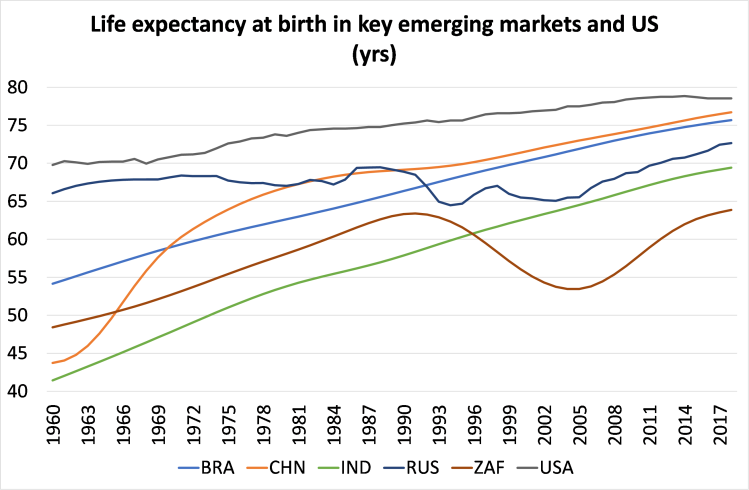

One of the results of this huge growth in per capital income has been a staggering rise in life expectancy. From life expectancy at birth in 1960 of just 44 years, China’s average life expectancy is now 77 years. It is catching up with the US, where there has been a fall since the end of the Great Recession. And China has outstripped all the other so-called large emerging economies.

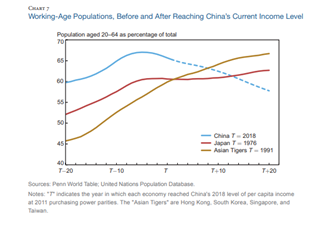

High life expectancy and falling birth rates have meant that China has an ageing population. Indeed, the working-age (20-64) population began shrinking in 2017.

Up to now, the key to China’s economic growth has been the huge expansion of investment in machinery and technique as China moved from the labour-intensive economy of the Mao period to a hi-tech manufacturing export economy now. Of the 8.7% annual real GDP growth in the two decades before 2007, 4.7% pts came from investment (55%) – and over one-third from ‘innovation’ (TFP). Labour inputs contributed less than 15%.

The NY Fed admits that if China keeps up this pace of expansion, it “is well on track to high-income status… After all, per capita income growth has averaged 6.2 percent over the last five years, implying a doubling roughly every eleven years, and per capita income is already close to 30 percent of the U.S. level.”

But NY Fed economists along with most Western economists reckon that this will not happen. China’s growth rate will slow down because it cannot expand capital investment any more than it has and its technical prowess will not rise sufficiently to compensate. Moreover, unless it drops state-led and directed investment and allows ‘the market’ and ‘the consumer’ to become king, it cannot achieve high income status and will be locked into the ‘middle -income trap’ as so many other ‘emerging’ capitalist economies have.

The NY Fed offers three growth scenarios for the next two decades. The ‘humdrum’ scenario projects that China will fail badly in reaching the living standards of the mature capitalist economies. Even under its ‘pretty good’ scenario it will fall short of the success of Japan and other East Asian states. Only the ‘golden’ scenario will do the trick.

But in the golden scenario, real per capita income growth must average a very rapid 4.9 percent from 2018 to 2028, slowing to a still strong 2.6 percent over 2028-38 (based on CB growth figures). This leaves real incomes up by 111 percent from their level in 2018, a performance comparable to what the Asian Tigers achieved over a similar period. China then achieves high-income status, with real incomes at slightly above 60 percent of the current US level, or exactly 50 percent of the assumed future US level.

The NY Fed reckons China’s growth rate will slow because investment growth will slow and productivity enhancement from innovation will not be enough to compensate for falling employment as China ages.“There is good reason to doubt that China could sustain rapid TFP growth with such a production mix, especially given already pressing concerns about the efficiency of new investment spending.”

The NY Fed reckons that it would be “pretty extraordinary – and historically unprecedented” for Chinese growth rates to be sustained at 5% a year for the next 20 years. Beijing-based Keynesian economist Michael Pettis echoes the Fed’s view: “China’s working population is expected to be 7% lower in 15 years than it is today. In that case 4.7% GDP growth requires as great an increase in worker productivity as 5.2% GDP growth for an economy with a steady working population.”

But is that growth target really so impossible? Given that China has achieved 7% annual growth (CB figures) over the last 20 years with labour inputs contributing only 15%, it does not seem impossible that even with a zero contribution from labour (and that won’t be the case) and no change in the investment rate, that China could not manage around 5% a year economic growth by achieving a moderate 1-2% a year TFP increase . Much will depend on whether the technology upgrade that China is engaged in can deliver. And even the NY Fed admits that “China can grow rapidly for a long time before it approaches the technological frontier. There is plenty of upside, just no guarantee that it will be exploited.” Moreover, even if China does not sustain 5% annual growth over the next two decades, it will close the gap with the mature economies because growth rates there will be lucky to get above 1-2% a year (and that’s assuming no crises of capitalist production up to 2040!).

The reason that the NY Fed as well as many Keynesian and other critics of the Chinese ‘miracle’ are so sceptical is that they are seeped in a different economic model for growth. They are convinced that China can only be ‘successful’ (like the economies of the G7!) if its economy depends on profitable investment by privately-owned companies in a ‘free market’ where consumption rules over investment. And yet the evidence of the last 40 and even 70 years is that a state-led, planning economic model that is China’s has been way more successful than its ‘market economy’ peers such as India, Brazil or Russia.

The NY Fed admits that “China (could) prove a unique case, attaining high-income status while retaining governance features unlike those of all current high-income economies.” However, the “Chinese authorities have been clear about their plans to proceed with market-oriented reforms. But authorities have been equally clear that the Communist Party will retain control over the commanding heights of the economy and over political life. And in this connection, policy is currently moving in the wrong direction, toward greater state and party control of the economy.” According to the critics, this is the ‘wrong direction’; but what will the CP plenum conclude?

In future posts, I shall look at the challenges facing the Chinese economy, apart from growth, including: rising debt; climate change and the environment; inequality; the Belt and Road project; and the intensifying ‘cold war’ with the US.

No comments:

Post a Comment