On their special website, Tax Justice Now, they present a wealth of data on the impact of taxation on the redistribution of income and wealth in the US. There is one staggering fact: for the first time in over century, The 400 American billionaires pay lower tax rates than their secretaries; something that billionaire investor Warren Buffet once jokingly suggested. His joke is confirmed as fact.

Even as they became fabulously wealthy, the ultra-rich have seen their taxes collapse to levels last seen in the 1920s. Meanwhile, working-class Americans have been asked to pay more.

Considering all taxes paid at all levels of governments in 2018, the authors find that: “Contrary to widely held view, US tax system is not progressive. The effective rate of tax takes into account all forms of taxation on the individual (income taxes, corporate tax, capital income taxes etc). On that measure for the top 400 income holders(billionaires) the effective tax rate is 23% while it is 25-30% for working and middle classes. America’s tax system is now technically ‘regressive’ and is “a new engine for increasing inequality.”

Why do the poor pay more as a share of their income? There are very regressive sales taxes: the US has a ‘poor man’s VAT’ not only on goods and services, but also through higher payroll taxes. And the rich pay less because income from capital (property and financial assets) is hardly taxed: corporation tax is low, and there are low rates on dividends and capital gains. Indeed, US federal corporate tax revenue almost halved in just one year (2018) with the Trump tax cuts.

Since 2010, it is mandatory to have health insurance in the US but it is mostly done through employers. The cost is about $13,000 per covered worker, irrespective of income. So health insurance premiums are like a huge poll tax administered by employers on behalf of government, with mandatory payments to private insurers. These insurance premiums are very regressive.

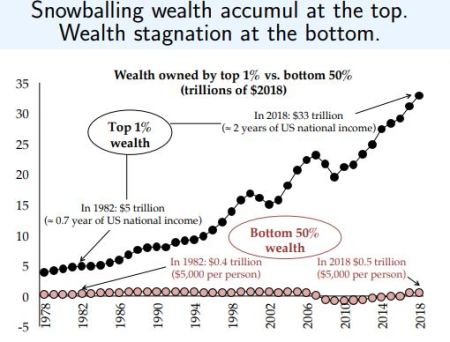

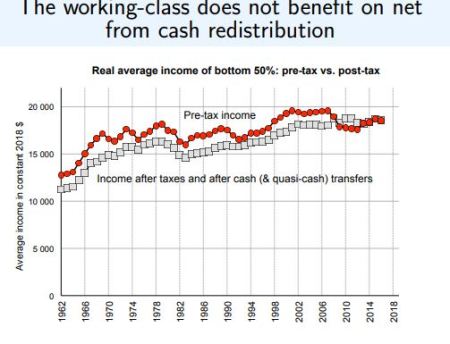

For the bottom 50% of income earners, average pre-tax income has stagnated since 1980, at $18,500 per adult. Out of this stagnating income, a rising share goes to paying taxes and health insurance. In contrast, at the top, there are booming pre-tax incomes and falling taxes. Thus inequality of income and wealth rises.

Saez and Zucman argue that there are three main drivers of declining progressivity: the collapse in capital taxation; allowing tax avoidance loopholes and outright evasion and; globalization with tax havens and competition to reduce taxes for foreign investment.

Everywhere, governments are competing to cut taxes for corporations: the global corporate tax rate has halved since 1980s. The rich incorporate and retain earnings within their firms and so can save tax free. They only get taxed when they spend, unlike the rest of us.

The Panama papers revealed the extent of international tax avoidance and evasion. And Zucman’s previous book showed that $7.6 trillion in assets were being held in offshore tax havens, equivalent to 8% of all financial assets in the world. In the past five years, the amount of wealth in tax havens has increased over 25%. There has never been as much money held offshore as there is today. In 2014, the LuxLeaks investigation revealed that multinationals paid almost no tax in Europe, thanks to their subsidiaries in Luxembourg. In the US, Americans can set up an ‘offshore company’ in Delaware or other states like Nevada – they don’t even need to go to Panama.

Nick Shaxson, in his devastating book, Treasure Islands, tax havens and the men who stole the world, exposed the workings of all these global tax avoidance schemes for the big corporations and how governments connive in it or allow it. Britain is already, on some measures, the biggest player in the global tax haven game. A spider’s web of satellite havens, from the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands to Jersey, captures wealth from around the world, polishes it and feeds it to the City of London. The British Overseas Territories like the British Virgin Islands or Jersey operate for these purposes and it’s the main source of revenue for these islands.

A new report from Transparency International, provides the latest evidence of the devastation Britain’s offshore spider’s web causes globally. It tots up £325bn of funds “diverted by rigged procurement, bribery, embezzlement and the unlawful acquisition of state assets”, from more than 100 countries – mostly in Africa, the former Soviet Union, Latin America and Asia. The financial criminals include a kingpin of a multibillion-pound scam to loot Malaysia, and a jailed former Moldovan prime minister. “Peppered throughout most major cases of bribery, embezzlement and rigged procurement,” says Transparency International, “you will find a UK nexus.”

Saez and Zucman propose to end these iniquities by stopping corporate tax evasion and tax competition and taxing extreme wealth, while funding health care and education through progressive income taxation. Corporate taxation should be on country-by-country profits. For example, if Apple pays 2% on the profits it books in Ireland, US would collect the missing 23% from the overall 25% tax rate. If Nestle pays 2% tax globally but makes 30% of its sales in the US, US would collect 30% of the 25% US tax rate. If there were an international agreement on a 25% corporate minimum tax as a pre-condition for further trade liberalization, then taxes would be at the heart of future trade deals. The infamous tax havens in countries and islands would be closed down.

But the main proposal to reverse rising inequality of wealth and income advocated by the authors is a wealth tax. Saez and Zucman estimate that with a 10% wealth tax above $1 billion, US wealth inequality can return to its 1980 level. This would also generate revenue to pay for health and education services. For example, the wealth tax proposal of Democrat candidate Elizabeth Warren starting at 2% above $50m of wealth to 10% for billionaires would raise 1% of GDP and would eventually “abolish billionaires gradually”. If there was a 90% top rate, it would “abolish billionaires now”.

The authors also propose a tax on all national income of 6% enough to fund health care for all. It would mean a big tax cut for the bottom 90%, allowing the abolition of all sales taxes and Trump tariffs. Consumption taxes would have no role in this ‘optimal tax’.

At a conference organised by the Peterson Institute, a mainstream think-tank, former Clinton Treasury secretary and Keynesian guru, Larry Summers attacked the wealth tax proposals. In particular, Summers argued that Saez and Zucman’s data exaggerated the regressive nature of the American system because they only looked at taxation and did not include transfers (social welfare benefits). Summers reckons: “government policy has become more redistributional if, as is proper, you include benefit.” On their website, Saez and Zucman dealt with issue of social transfers. They found that, even after transfers, below average households benefited little from redistribution. “Since it can be hard to know who benefits from certain forms of government spending (e.g., defense spending)”.

Summers then denied that wealth inequality was an important measure for redistribution. What if we had a “super effective social insurance against retirement, disability & health expenses?” Then average households would not save so much and would spend their assets. So the measure of wealth inequality would rise although people were actually better off! But whether inequality would fall as the result of a ‘super effective social insurance’ is debatable. And anyway we don’t have such a system and wealth inequality is very high now. Summers does not answer the basic question: why is inequality so high in the US? At least, Saez and Zucman attempt to do so, blaming it on regressive taxation and tax havens.

Summers’ most excruciating argument against a wealth tax was that “forcing the wealthy to spend could boomerang. If the wealth tax had been in place a century ago, we would have had more anti-semitism from Henry Ford and a smaller Ford Foundation today.” He implies that a wealth tax would force billionaires to put more money into tax-avoiding ‘foundations’ that could be used to promote nasty right-wing policies and attitudes like Henry Ford’s foundation in the 1930s. So you see a wealth tax could generate more fascism from the rich!

Summers had to withdraw that implication. But his conclusion stems from the assumption that billionaire foundations and charities are the best way to redistribute wealth, namely at the whim of a rich individual rather than through government social distribution. Surely, the rich should pay taxes and everybody should get free public education and health, and get rid of private schools and hospitals funded by billionaire donations.

Summers is on stronger ground when he argued that a wealth tax won’t stop the rich controlling the political system: “there is a very real problem, but the wealth tax will not be remotely effective in addressing it. It costs $5 million a year at maximum to be a a central player in either political party. This will be easily affordable for the rich even with a wealth tax. Very few of the problems today involve personal contributions of the wealthy. They instead involve corporate contributions or large groups: e.g., the NRA, the insurance industry, sugar producers”. Summers went on: “Saez was unable to provide even a single example of a specific instance of excessive political power that the wealth tax would address.”

And this is right. The real control of American society is through the big corporations and their lobbyists; wealthy individual billionaires play a minor role in that. It is the concentration of capital at the top through the grip of a few hundred corporations in the US and globally that is at the essence of power, control and wealth. A wealth tax on billionaires will help state revenues and reduce inequalities to some extent. But the power of capital would not really be dented.

Of course, Summers was not making this point to propose taking over big capital, but the opposite: to reject a wealth tax on the rich. But it does expose the weakness of Saez and Zucman’s policy proposals. They only deal with redistributing income and wealth after the event. But rising wealth and income inequality are not due to regressive taxation in the main, but to the structure of investment, production and income in the capitalist economy, namely the exploitation of labour by capital.

Indeed, rising inequality in the US and in all the major economies only kicked in from the 1980s onwards when public sector spending on health prevention and care and on education was cut back (neoliberalism); all to reverse the low levels of profitability for capital reached globally in the early 1980s. But inequality of wealth and income existed even in ‘the golden age’ of the 1950s and 1960s. It was lower mainly because of the strength of the labour movement, high investment in productive sectors as opposed to finance and real estate – and also higher taxation.

The reason for rising inequality from the 1980s was a rise in income going to capital in the form of profits, rent and interest and not due to the more skilled labour getting higher income than the less skilled. And this rising capital-income ratio was driven mainly by inherited wealth. ‘From rags to riches’ is not the story of capitalist wealth: it is more ‘From father to son’ or ‘From husband to widow’.

This is what Thomas Piketty showed in his book, Capital in the 21st century. But because he conflated capital into wealth by including non-productive assets like housing, stocks and bonds in his measure, he lost sight of how wealth is created and appropriated, as Marx shows with his law of value: namely through exploitation. As a result, Piketty (and his colleagues Saez and Zucman) have policy prescriptions for a better world that are confined to progressive taxation and a global wealth tax to ‘correct’ capitalist inequality.

And yet Piketty et al recognise that it is utopian to expect the wealthy (who control governments) to agree to a reduction in their own wealth. They do not suggest another way to achieve a reduction in inequality: namely, to raise wage income share through labour struggles and to free trade unions from the shackles of labour legislation.

And they do not propose more radical policies to take over the banks and large companies, stop the payment of grotesque salaries and bonuses to top executives and end the risk-taking scams that have brought economies to their knees. For them, the replacement of the capitalist mode of production is not necessary, only a redistribution of the wealth and income already accrued by capital. Abolish the billionaires by taxation, not by expropriation.

No comments:

Post a Comment