The recent release of the US jobs data for May, which apparently showed a reduction in the unemployment rate from April, sparked a sharp rally in the US stock market. And if you were to follow the stock markets of the major economies, you would think that the world economy was racing back to normal as the lockdowns imposed by most governments to combat the spread of COVID-19 pandemic are relaxed and even ended.

The stock markets of the world, after dropping precipitately when the lockdowns began, have rocketed back towards previous record levels over the last two months. This rally has been driven, first, by the humungous injections of money and credit into the financial system by the major central banks. This has enabled banks and companies to borrow at zero or negative rates with credit guaranteed by the state, so no danger of loss from default. At the same time, governments in the US, UK and Europe have made direct bailout funds to major companies stricken by the lockdowns, like airlines, auto and aircraft makers, leisure companies etc.

It’s a feature of the 21st century that central banks have become the principal support mechanism for the financial system, propping up the leverage that had grown during the ‘great moderation’ a phenomenon that I detailed in my book, The Long Depression. This has combated the low profitability in the productive value-creating sectors of the world capitalist economy. Companies have increasingly switched funds into financial assets where investors can borrow at very low rates of interest to buy and sell stocks and bonds and make capital gains. The largest companies have been buying back their own shares to boost prices. In effect, what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’ has risen in ‘value’ while real value has stagnated or fallen.

Between 1992 and 2007, central bank monetary injections (“power money”) doubled as a share of global GDP from 3.7% of total ‘liquidity’ (money and credit) to 7.2% in 2007. At the same time, bank loans and debt nearly tripled as a share of GDP. From 2007 to 2019, power money doubled again as a share of the ‘liquidity pyramid’. Central banks have been driving the stocks and bond market boom.

Then came Covid-19 and the global shutdown that has pushed economies into a deep freeze. In response, the G4 central bank balance sheets have grown again, by around $3trn (3.5% of world GDP), and this rate of growth is likely to persist through to year-end as the various liquidity and lending packages continue to be expanded and drawn down. So power money will double again by the end of this year. That would push global power money up to $19.7trn, almost a quarter of world nominal GDP, and three times larger as a share of liquidity compared to 2007.

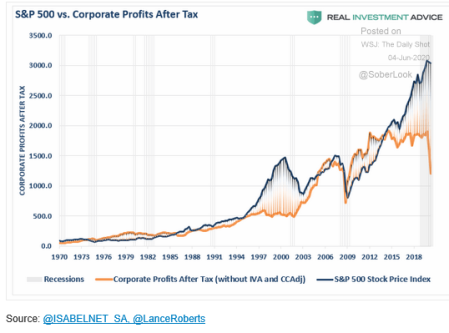

No wonder stock markets are booming. But this fantasy world of finance increasingly bears no relation to the production of value in capitalist accumulation. While the US stock market races back to its previous levels, corporate profits in the pandemic lockdown are suffering sharpest fall since the Great Recession of 2008-9. The gap between fantasy and reality is even greater than it was in the late 1990s just before the dot.com bust that saw stock valuations collapse by 50%, to turn the fictitious into the real.

But the other reason why the financial markets are booming is the optimistic belief promoted by governments that the COVID-19 disaster will soon be over. The argument goes that this year will be terrible for GDP, employment, incomes and investment in the ‘real’ economy, but everything is set to bounce back in 2021 as the lockdowns end, the miracle vaccine comes along and thus there is a quick ‘return to normal’. The speculators are looking to jump over the chasm of the pandemic slump to the other side where things can motor on again.

In the US, the May employment figures showed a sharp recovery in jobs created. As the lockdowns started to end or relax in the US, it seems that many Americans are returning to work in the leisure and retail sectors after being furloughed for two months. The stock market loved this, assuming that the V-shape is happening. But the US unemployment rate was still 13.3%, or more than one-third higher than in the depths of the Great Recession. And if you include those wanting full-time work but cannot get it, the U-6 category, then the unemployment rate was 21%, and adding another 3m people who were not classified, the total unemployment rate in May is more like 25%. Moreover the rate for blacks rose.

The return to work of some retail and leisure employees is only to be expected. The question is whether getting GDP and investment growth back to previous (relatively weak levels) and employment with it is possible in any short span of time. Most forecasters don’t’ think so. Indeed, while the stock markets head back to previous highs buoyed on the hope of a V-shaped recovery, most mainstream economic forecasts are predicting doom and a lengthy drawn out return, with some expecting no return to previous trends at all.

As I have argued in previous posts, the world capitalist economy was not motoring along at a pace before pandemic hit. Indeed, in most major economies and in the so-called larger emerging economies, growth and investment had already slowed to a trickle, while corporate profits had stopped growing at all. The profitability of capital in the major economies was near a post-war low, despite the apparent mega-profits being made by the so-called FAANGS, the techy media giants.

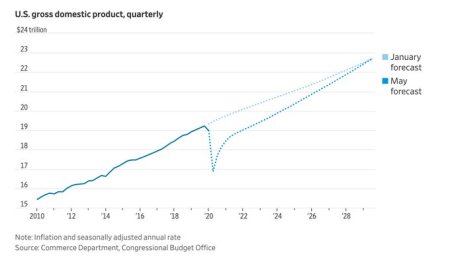

The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has drastically revised down its real GDP forecast for the US. It now expects US nominal GDP to fall 14.2% in the first half of 2020, from the trend it forecast in January before the COVID-19 pandemic broke. Then it expects the various fiscal and monetary injections by the authorities and the end of the lockdowns to reduce this loss from the January figure to 9.4% by end 2020. The CBO still expects a sort of V-shaped recovery in US GDP in 2021 but does not expect the pre-pandemic crisis trend in US economic growth (already reduced in the Long Depression since 2009) to be reached until 2029 and may not even return to the previous trend growth forecast until after 2030! So there will be a permanent loss of 5.3% in nominal GDP compared to pre-COVID forecasts – $16trn in value lost forever. In real GDP terms, the loss will be about 3% cumulatively, or $8trn in 2019 money. And this assumes no second wave in the pandemic and no financial collapse as companies go bust.

It’s a similar forecast for Europe. After euro area real GDP registered a record decline of 3.8% in the first quarter of 2020, the ECB predicts a further decline in GDP of 13% in the second quarter. Assuming the pandemic lockdowns come to an end and fiscal and monetary measures are effective in helping the EZ economy, the ECB reckons that real GDP in the euro area will still fall by 8.7% in 2020 and then rebound by 5.2% in 2021 and by 3.3% in 2022. But real GDP would still be around 4% below the level originally expected before the pandemic. Unemployment will be still be some 20% above the forecast before the pandemic. And that’s the ‘mild scenario’. Under a more severe scenario where there is second virus wave and further restrictions, the ECB forecasts that the Euro area will still be some 9% below previous expected levels in 2022 and not return to ‘normal’ for the foreseeable future!

Outside the Eurozone, the already weak UK economy is unlikely to manage a V-shape rally. Historically, low growth has persisted in the UK after recessions – there is permanent scarring. There is even less reason to assume that this time is different.

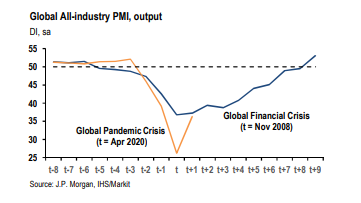

And when we look at the indicators for global economic activity, levels remain severely depressed in May, indeed at levels below the bottom of the slump of 2008-9.

As for the ‘emerging economies’, the picture is even grimmer. If you believe the mainstream forecast for a -10% fall in 2020, Argentina’s GDP this year will drop back to its 2007 level. For Brazil, the forecast of -7% in 2020 takes the economy back to 2010 – ten years of gains in GDP gone. Mexico’s fall of -9% returns it to 2013. A “lost decade” even before you factor in currency devaluation effects. Over a ten-year horizon, Brazil and Argentina will end up with lower real GDP levels after 20 years of the 21st century than 30 years ago.

Most important as a guide to whether the major capitalist economies can ‘return to normal’ as the US stock market investors jubilantly reckon is the level of profitability of capital. The first quarter figures for US corporate profits showed the direction for the future. US corporate profits fell at a 13.9% annual pace and were 8.5% below the first quarter of last year. The key productive sectors (non-financial) saw profits fall by a staggering $170bn in the quarter, so that there was no increase in profits compared to Q1 2019 – and that does not take into account inflation. Indeed, US non-financial sector profits have been in decline more or less for the last five years, so 2020 will only add to the problems of the US corporate sector in trying to come out of this pandemic lockdown with the same previous levels of investment, production and employment.

Indeed, if you look at the profitability (not the mass of profits) of the G7 economies, then more likely than a return to normal (weak as that was) is another leg down in this Long Depression that the major imperialist economies have experienced (with short up and down bursts) since 2009. Look at this graph of G7 profitability of capital.

This comes from the data provided by the Penn World Tables 9.1. It is the internal rate of return on net capital series (new to the Tables). I have weighted the profitability by GDP for the top seven advanced capitalist economies (G7). What is interesting for this post is that we can see that the profitability of capital actually peaked (as a weighted average) in 1997 and the whole two decades of the 21st century is one of a trend fall in profitability (interspersed with short upturns (2001-2005, 2009-10). I have extended the Penn IRR estimate (which ends in 2017) to 2021 using the EU AMECO database estimates (which are similarly calculated to the Penn IRR). In doing that, the G7 profitability of capital will likely plunge to all-time low in 2020 and make only a moderate bounce back in 2021.

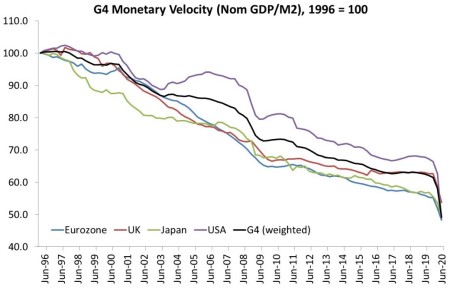

Financial markets may be expecting a quick return (and investors riding this forecast are making huge profits right now). But the reality is that the financial market boom is floating on an ocean of free credit provided by the state and central bank monetary financing. This credit is not making its way into rising economic activity, as the measure of the velocity of money (the speed of money transactions) shows. The credit-fuelled boom in fictitious capital has not driven faster growth in real value or profitability. It’s pushing on a string.

Debt has built up far faster than any rise in value. Indeed, the ‘productivity of debt’ (IDOR) has gone negative.

Keeping asset markets up is one thing; getting 35m Americans back to work is quite another, particularly when most are employed by businesses that don’t enjoy the benefits of being in the S&P 500 and are a long way from the leading tech firms that have propped up stock price indexes.

The reality is that the pandemic, in an economy where growth was already on a downward trajectory and productivity growth was low, has merely reinforced existing trends. The increase in debt that the surge in power money facilitates will act as a further drag on growth. Despite the optimism of the financial markets, a return to normal is disappearing over the horizon.

No comments:

Post a Comment