This is a balanced, sober look at the Chinese economy and society from Marxist economist, Michael Roberts and useful information for working class people wanting to understand the nature of this rising world power. Richard Mellor Admin.

China in the post-pandemic 2020s

by Michael Roberts

China’s National Peoples Congress (NPC) opened today, having been delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. The NPC is China’s version of a parliament and used by the Communist party leaders to report on the state of the economy and outline their plans for the future, both domestically and globally.

Prime Minister Li Keqiang announced that for the first time in decades that there would be no growth target for the year. So the Chinese leaders have abandoned their much heralded aim to have doubled the country’s GDP under the current plan by this year. That was bowing to the inevitable.

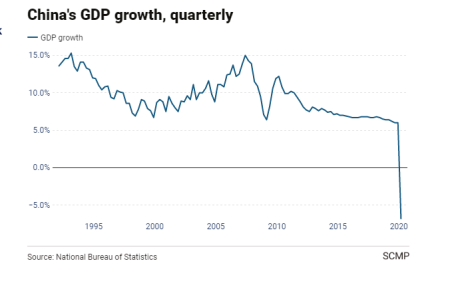

The pandemic and lockdown had driven the Chinese economy into a severe contraction for several months, from which it is only just recovering. The economy contracted by 6.8 per cent in the first quarter and most forecasts for the whole year are for less than half of the 6.1 per cent growth rate posted last year. But even that figure would be way better than all the G7 economies in 2020.

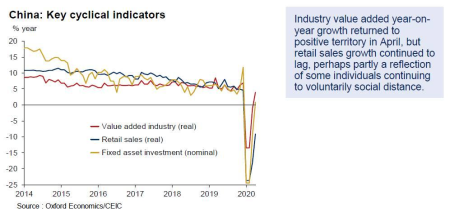

Industrial production and investment is now picking up, but consumer spending remains depressed.

But Li said that main reason that there was no growth target was because of uncertainty about “the Covid-19 pandemic and the world economic and trade environment.” In other words, even if the domestic economy is recovering, the rest of the world is still depressed. With world trade contracting, there are slim prospects for the exports of the manufactures that China has mainly depended for its expansion.

China is ahead of other major economies in coming out of the pandemic. But even Li had to admit that a lot of mistakes were made in handling the pandemic and there was “still room for improvement in the work of government,” including delays in alerting the public allowed the virus to spread.

“Pointless formalities and bureaucratism remain an acute issue. A small number of officials shirk their duties or are incapable of fulfilling them. Corruption is still a common problem in some fields,” Li admitted. Nevertheless, compared to the performance of governments in the West, China had done much better in keeping cases and deaths down.

In the short term, Li said the government intends to give a boost to the economy with some fiscal stimulus and monetary easing, similar to that in the G7 economies. China is targeting a 2020 budget deficit of at least 3.6% of GDP, above last year’s 2.8%, and increased funding for local-government borrowing by two-thirds. And for the first time, the central government will issue bonds to be used to help local government spending and firms in difficulty. Unemployment is officially recorded at 5.5% but it is probably more like 15-20%, so the government aims to create more jobs and reduce poverty in rural areas to curb the flood of rural migrants to the cities.

That brings us to discuss the long-term future of the Chinese economy in the post-pandemic world and in the context of the intensifying trade and technology war with the US and other imperialist powers.

In my view there are three ways of looking at the economic development of China (this is something that I have written on in detail in a recent paper for the Austrian Journal of Development Studies). The mainstream economics view is that China should become a full ‘market’ economy like those of the G7. Relying on cheap labour to sell manufacturing goods to the West is over. Rising labour costs show that China’s state-driven and led economic model cannot succeed in developing modern technology or delivering consumer goods to the people. This was the policy advice of the World Bank and other international agencies of global capital in the past and it gained some traction among a section of the elite, especially those closely connected to China’s private billionaires. But so far, this option has been rejected by the majority in the current leadership.

The second view is what might be called Keynesian. It recognises the success of the Chinese economy in the last 30 years in taking nearly 900m people out of the official poverty level set by the World Bank. Indeed, the World Bank has just adjusted its figures for the decline in those who are now under its poverty level. The decline seems impressive, until you realise that 75% of those brought out of poverty globally in the last three decades are Chinese.

This Keynesian view argues that China’s success has been based on massive investment in industry and infrastructure which has enabled the country to become the world’s manufacturing powerhouse. But now that emphasis on industrial investment must be changed because household consumption is weak and in a modern economy it is consumption that matters. Unless there is a swing to consumption, the Chinese economy will slow and the huge level of corporate and household debt will increase the risk of financial crises.

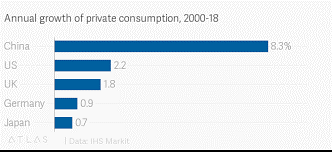

Actually, personal consumption in China has been increasing much faster than fixed investment in recent years, even if it is starting at a lower base. Consumption rose 9% last year, much faster than GDP. And consumption growth would be even faster if the government took steps to reduce the high level of inequality of income.

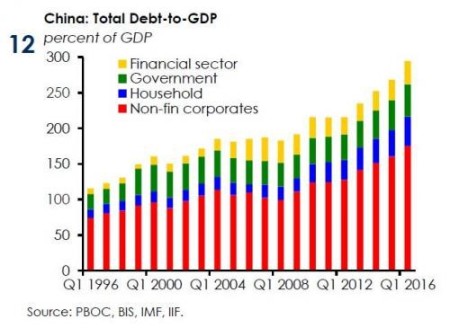

The idea that China is heading for a crash because of under consumption and over investment is not convincing. It’s true that according to the Institute of International Finance (IFF), China’s total debt hit 317 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of 2020. But most of the domestic debt is owed by one state entity to another; from local government to state banks, from state banks to central government. When that is all netted off, the debt owed by households (54% of GDP) and private corporations is not so high, while central government debt is low by global standards. Moreover, external dollar debt to GDP is very low (15%) and indeed the rest of the world owes China way more, 6% of global debt. China is a huge creditor to the world and has massive dollar and euro reserves, 50% larger than its dollar debt.

It’s true that some of the fixed investment expansion may have been wasted. Indeed, the Keynesian development model of China based on just rising investment and private consumption demand is increasingly flawed. As President Xi Jinping said, “Houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation.” But the government allowed capitalist speculation in property so that 15% of all apartments currently are owned as investments, often not even connected to electricity supply. This property speculation was fuelled by credit funded by the state banks but also by ‘shadow banking’ entities. This sort of speculation wasted resources and did not direct investment into areas like reducing CO2 emissions to meet the government’s declared aim to make China a ‘clean economy’. With China’s population peaking in this decade and the working age population falling 20% by 2050, the aim of investment must be towards job creation, automation and productivity growth.

That brings me to the third development model, the Marxist one. The key to prosperity is not market forces (neoclassical mainstream) or investment and consumption demand (Keynesian) but in raising the productivity of labour in a planned and harmonious way (Marxist).

In a capitalist economy, companies compete with each other to raise profitability through the introduction of new technologies. But there is an inherent contradiction under capitalist production between a falling profitability of capital and a rising productivity of labour. As capitalists try to raise the productivity of labour by shedding labour with technology and so lowering labour costs and increasing profits and market share, the overall profitability of investment and production begins to fall. Then, in a series of crises, investment collapses and productivity stagnates.

This is clearly an issue for China in its more mature stage of accumulation in the 21st century – if you accept that China is just another capitalist economy like the imperialist powers or the emerging ones like Brazil or India. The argument goes, that China may be different from the ‘liberal capitalism’ of the West and instead is an autocratic ‘political capitalism’, as Branco Milanovic describes China in his book, Capitalism Alone, but it is still capitalism.

If you accept that view, then we can gauge the health and future of China’s economy by measuring the profitability of its burgeoning capitalist sector. In a new paper (Catching Up China India Japan (1)), Brazilian Marxist economists, Adalmir Marquetti, Luiz Eduardo Ourique and Henrique Morrone compared China’s development to that of India in catching up with the G7 economies. They show that the high capital accumulation rate in China has led to a fall in profitability even lower than in the US, so that further expansion is at risk. In another paper, they argue that there is now an overaccumulation crisis brewing and further heavy investment would not work, especially given rising greenhouse emissions it would create. 71548-211901-1-PB (1)

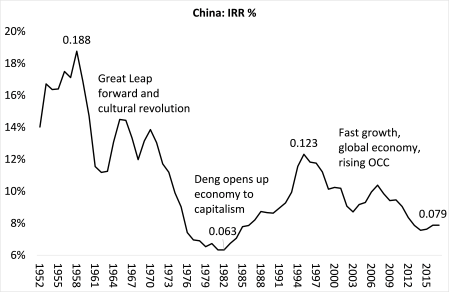

Like Marquetti et al, I have measured the profitability of the capitalist sector in China (from Penn World Tables 9.1 internal rate of return on capital series) and I find a similar fall. The huge expansion of investment and technology, particularly once global markets were opened up to Chinese industry after 2000 when joining the World Trade Organisation, led to double-digit growth rates up to the Great Recession of 2008. But the increased organic composition of capital drove profitability down prior to global pandemic crisis, and eventually growth slowed.

Does this mean that China is heading for major slump along classic capitalist lines some time in this decade? Marquetti et al seem to suggest that: “The larger profit rate explained the robust mechanization in the early stages of the process. Fast capital accumulation diminishes capital productivity and the profit rate. Then, the success in catching up must hinge on raising the saving and investment rates. It may further reduce capital productivity and the profit rate, putting the process at risk, which seems to be the case in China and India.” And they quote Minqi Li that ‘‘if China were to follow essentially the same economic laws as in other capitalist countries (such as the United States and Japan), a decline in the profit rate would be followed by a deceleration of capital accumulation, culminating in a major economic crisis.’’

But the question for me is whether the capitalist sector in China’s economy is dominant. Does China follow the same law of value as other capitalist economies? China seems to be more than just an autocratic, undemocratic, ‘political’ version of capitalism compared to the ‘liberal democratic’ version of the West (as argued by Milanovic). Its economy is not dominated by the market, by investment decisions based on profitability; or by capitalist companies and bosses; or by foreign investors. Its economy is still dominated by state control, state investment, state banks and by Communist apparatchiks who control the big companies and plan the economy (often inefficiently as there is no accountability to China’s working people).

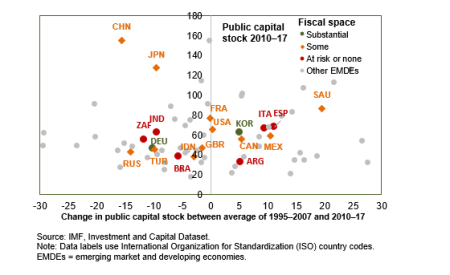

I remind readers of the study I made a few years ago of the extent of state assets and investment in China compared to any other country. It showed that China has a stock of public sector assets worth 150% of annual GDP; only Japan has anything like that amount at 130%. Every other major capitalist economy has less than 50% of GDP in public assets. Every year, China’s public investment to GDP is around 16% compared to 3-4% in the US and the UK. And here is the killer figure. There are nearly three times as much stock of public productive assets to private capitalist sector assets in China. In the US and the UK, public assets are less than 50% of private assets. Even in ‘mixed economy’ India or Japan, the ratio of public to private assets is no more than 75%. This shows that in China public ownership in the means of production is dominant – unlike any other major economy.

And now the IMF has published new data that confirm that analysis. China has public capital stock near 160% of GDP, way more than anywhere else. But note that this public sector stock has been falling faster than even the neo-liberal Western economies. The capitalist mode of production may not be dominant in China, but it is growing fast.

Which way will China go? In the post-pandemic decade will it move towards an outright capitalist economy that is just like the rest of world? In other words, adopting the neoliberal mainstream model. So far, in the light of the disastrous failure of ‘liberal democratic’ market economies in handling the pandemic, with death rates 100 times higher than in China and now deep in a slump not seen since the 1930s, that market model does not seem attractive to the Communist dictatorship or the Chinese people. Instead Xi and Li seem to want to continue and expand the existing model of development: a state-directed and controlled economy that curbs the capitalist sector and resists imperialist intervention.

Indeed, China looks to expand its technological prowess and its influence globally through the Belt and Road investment initiative and its huge lending programmes to the likes of African and other states. And it will be able to do so because its economic model does not rest on the falling profitability of its admittedly sizeable capitalist sector. An IIF report found that China is now the world’s largest creditor to low income countries.

That is why the post-pandemic strategy of imperialism towards China is taking a sharp turn. And this is the big geopolitical issue of the next decade. The imperialist approach has changed. When Deng came to take over the Communist leadership in 1978 and started to open up the economy to capitalist development and foreign investment, the policy of imperialism was one of ‘engagement’. After Nixon’s visit and Deng’s policy change, the hope was that China could be brought into the imperialist nexus and foreign capital would take over, as it has in Brazil, India and other ‘emerging markets’. With ‘globalisation’ and the entry of China to the World Trade Organisation, engagement was intensified with the World Bank calling for privatisation of state industry and the introduction of market prices etc.

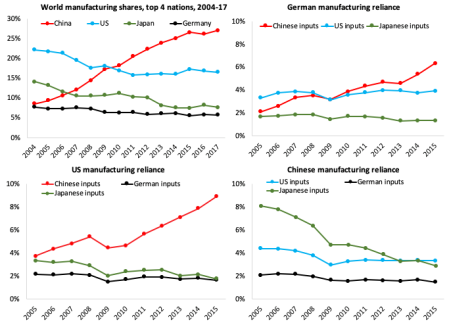

But the global financial crash and the Great Recession changed all that. Under its state controlled model, China survived and expanded while Western capitalism collapsed. China was fast becoming not just a cheap labour manufacturing and export economy, but a high technology, urbanised society with ambitions to extend its political and economic influence, even beyond East Asia. That was too much for the increasingly weak imperialist economies. The US and other G7 nations have lost ground to China in manufacturing, and their reliance on Chinese inputs for their own manufacturing has risen, while China’s reliance on G7 inputs has fallen.

Source: Manufacturing shares from World Development Indicator online database. Reliance computations by authors, based on OECD ICIO Tables (https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/inter-country-input-output-tables.htm).

So the strategy has changed: if China was not going to play ball with imperialism and acquiesce, then the policy would become one of ‘containment’. The sadly recently deceased Jude Woodward wrote an excellent book describing this strategy of containment that began even before Trump launched his trade tariff war with China on taking the US presidency in 2016. Trump’s policy, at first regarded as reckless by other governments, is now being adopted across the board, after the failure of the imperialist countries to protect lives during the pandemic. The blame game for the coronavirus crisis is to be laid at China’s door.

The aim to is weaken China’s economy and destroy its influence and perhaps achieve ‘regime change’. Blocking trade with tariffs; blocking technology access for China and their exports; applying sanctions on Chinese companies; and turning debtors against China; this may all be costly to imperialist economies. But the cost may be worth it, if China can be broken and US hegemony secured.

China is not a socialist society. Its autocratic one-party Communist government is often inefficient and it imposed draconian measures on its people during the pandemic. The Maoist regime suppressed dissidents ruthlessly and the cultural revolution was a shocking travesty. The current government also suppresses minorities like the grotesque herding of the muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang Province into ‘reeducation camps’. And nobody can speak out against the regime without repercussions. And now the leadership has announced the introduction of military rule in Hong Kong, ending parliament and suppressing the protests there. And it still looks to ensure that Taiwan, the home of the former warlord nationalists who fled to Formosa and occupied it at the end of the civil war in 1949, is eventually incorporated into the mainland.

China’s leadership is not accountable to its working people; there are no organs of worker democracy. And China’s leaders are obsessed with building military might – the NPC heard that the military budget would rise by 6.6 per cent for 2020 and China now spends 2% of GDP on arms. But that is still way less than the US. The US military budget in 2019 was $732bn, representing 38 per cent of global defence spending, compared with China’s $261bn.

But remember, all China’s so-called ‘aggressive behaviour’ and crimes against human rights are easily matched by the crimes of imperialism in the last century alone: the occupation and massacre of millions of Chinese by Japanese imperialism in 1937; the continual gruesome wars post-1945 conducted by imperialism against the Vietnamese people, Latin America and proxy wars in Africa and Syria, as well as the more recent invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan and the appalling nightmare in Yemen by the disgusting US-backed regime in Saudi Arabia etc. And don’t forget the horrific poverty and inequality that weighs for billions under the imperialist mode of production.

The NPC reveals that China is at a crossroads in its development. Its capitalist sector has deepening problems with profitability and debt. But the current leadership has pledged to continue with its state-directed economic model and autocratic political control. And it seems determined to resist the new policy of ‘containment’ emanating from the ‘liberal democracies’. The trade, technology and political ‘cold war’ is set to heat up over the rest of this decade, while the planet heats up too.

No comments:

Post a Comment