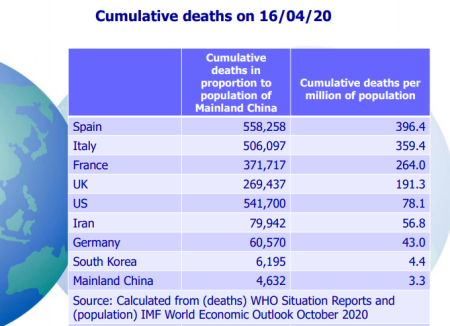

This coming Thursday 23 April there is a video conference meeting of the EU leaders to discuss once again what to do about the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing lockdown of production across the area. In particular, there is the vexed question of how to help out those EU members states like Italy and Spain that have been hit hardest by the pandemic. (Here are the latest figures compiled by John Ross).

Last week, over three days and two nights of teleconference, the finance ministers of the Eurozone fumbled their way towards an emergency response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain) aimed high with a demand that the Eurozone states share the burden of the crisis with a jointly issued debt instrument known as a coronabond. The FANGs (Finland, Austria, Netherlands, Germany) or ‘frugal four’ beat them back down, proposing that each member of the currency union bear its debts alone.

The Dutch finance minister Wopka Hoekstra played bad cop. He rejected a ‘mutual bond’ guaranteed by all states, arguing that it was Italy’s fault that it had such high public debt that it could not afford to pay for the pandemic itself. He did not trust the ‘profligate’ spending ways of the likes of Italy. This echoed the Eurogroup’s callous stance against Greece during the so-called ‘euro debt crisis’ of 2012-15.

The southern states, backed by France, protested that the Dutch minister’s position stood against the whole idea of the European project, supposedly designed to bring warring European nations into one integrated and harmonious whole. “We leave nobody behind,’ the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, proclaimed in her opening speech to the EU parliament at the beginning of 2020. “We need to rediscover the power of co-operation,’ she told the World Economic Forum in Davos three months ago, ‘based on fairness and mutual respect. This is what I call “geopolitics of mutual interests”. This is what Europe stands for.’

These fine words turned to dust at the finance ministers meeting. In the end, the weak southern states capitulated to the ‘frugal four’, as they had no alternative. Mário Centeno, the Portuguese finance minister and current Mr Euro, brokered a late night compromise. ‘At the end of the day, or should I say, at the end of the third day,’ he announced, ‘what matters the most is that we rose to the challenge.’

But the ‘compromise’ falls way short of helping Italian capitalism out of its mess. The finance ministers agreed on a package of 500 billion euros to alleviate the crisis. An ESM credit line will be established (up to 240 billion euros), which, although only subject to minor conditionality, will be limited to covering “direct and indirect” health costs. But this credit line will probably not be used by Italy, already burdened by sky-high public sector debt (only surpassed by Greece).

There will be a EU programme to grant member states cheap loans without conditions to support short-time work, which is called SURE (Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency). This will enable the EU to borrow on the markets and to pass on the funds to the member states. But this is just a short-term measure. Furthermore, there will be loan guarantees from the European Investment Bank for companies.

And the ECB is now buying up government bonds on a large scale under the PEPP (“Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme”). The PEPP program is thus currently ensuring that the Italian government can continue to refinance itself at very low cost during the corona crisis.

But all these are short-term measures or leave Italy burdened with yet more debt. Greece got the same treatment in the euro crisis and now has so much debt that it will never be able to pay it off this century, while the interest on that debt eats into the available tax revenues needed to provide public services and investment.

French President Macron has wailed at the Euro finance ministers’ decision. He warned that the EU was in danger of unravelling unless it embraces ‘financial solidarity’. His solution was a joint virus recovery fund that “could issue common debt with a common guarantee” to finance member states according to their needs rather than the size of their economies. “You cannot have a single market where some are sacrificed,” he added. “It is no longer possible . . . to have financing that is not mutualised for the spending we are undertaking in the battle against Covid-19 and that we will have for the economic recovery.” Yes, he knows that this was “against all the dogmas, but that’s the way it is”. He meant mainstream neoclassical austerity measures.

Macron recalled France’s “colossal, fatal error” in demanding reparations from Germany after the first world war, which triggered a populist German reaction and the disaster that followed. “It’s the mistake that we didn’t make at the end of the second world war,” he said. “The Marshall Plan, people still talk about it today . . . we call it ‘helicopter money’ and we say, ‘we must forget the past, make a new start and look to the future’.”

Here Macron echoed the criticism of John Maynard Keynes in his famous critique of the imposition of reparations imposed by France, Britain and the US on Germany after WW1. Keynes called for a Scheme for the Rehabilitation of European Credit where Germany would issue bonds and the former enemy nations would guarantee the German bonds severally and jointly, in certain specified proportions. This Keynesian solution is in essence what is being proposed now with EU coronabonds, to be financed and guaranteed by all member states.

But even if coronabonds were introduced would that be enough or even the right ‘solution’ to the massive slump that is now hitting Italy and all the weaker states of the EU? As right-wing Italian ‘populist’ Matteo Salvini commented: ‘I don’t trust loans coming from the EU. I don’t want to ask for money from loan sharks in Berlin or Brussels … Italy has given and continues to give billions of euros each year to the EU and it deserves all the necessary support, but not through perverse mechanisms that would mortgage the country’s future.’

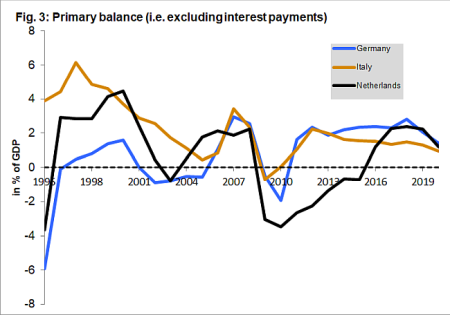

Italy has a huge public sector debt burden, not because the government has engaged in profligate spending. On the contrary, the government has adopted permanent austerity, running annual surpluses of tax revenues over spending (excluding debt interest) for 24 out of the last 25 years!

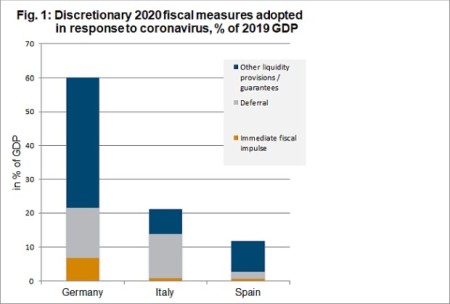

This austerity has meant the running down of public services, the degradation of the health system so it could not cope with pandemic and has added to the terribly poor growth in productivity and investment for over two decades. As a result, Italian government support in the pandemic will be minimal. The immediate fiscal impulse for Germany (in the form of additional government spending on medical equipment, short-time work, subsidies for small and medium-sized enterprises, etc.) amounts to around 7% of economic output in 2020, compared with only 0.9% for Italy.

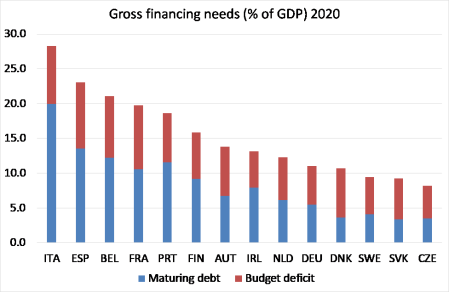

The Italian economy has been in permanent crisis, but the negative economic effects of the Corona shock have worsened it. On its own, Italy will not be able to get the economy back on track after the Corona lockdown. According to the latest estimates by the IMF, nobody in Europe will have higher gross financing needs (maturing debt and budget deficit) than Italy.

All a coronabond would do is tide Italy’s finances over for the period of the slump, but offer no way to restore the economy, employment and investment. After the slump, Italy’s public debt would be even higher than the 130% of GDP it is now. The IMF expects the annual primary surplus on government finances to turn into a 5% of GDP deficit, while debt to GDP rises to 155%. That is why the interest being demanded by those prepared to buy Italian government bonds has been rising, especially relative to Germany, where the interest is actually negative.

Italian 10yr government bond yield (%)

The reality is that Italian capitalism (like that of Greece) is just too weak to turn things around.

I shall return to the unending tragedy of Greece and its prospects in the COVID crisis in a future post. But why is Italian capitalism so weak? And more to the point, why has Italy’s membership of the Eurozone not produced a stronger Italian economy? The answer lies with the nature of capitalist accumulation. Unifying various nation states into one fiscal and monetary unit poses huge problems for capitalism. Historically, it has only been achieved through military conquest or civil war (the federal union of the US was achieved that way by the military defeat of the southern states).

Capitalism is an economic system that combines labour and capital, but unevenly. The centripetal forces of combined accumulation and trade are often more than countered by the centrifugal forces of development and unequal flows of value. There is no tendency to equilibrium in trade and production cycles under capitalism. So fiscal, wage or price adjustments will not restore equilibrium and anyway may have to be so huge as to be socially impossible without breaking up the currency union.

When the Euro was devised, the aim was to bring about closer convergence and integration of EU states by monetary union. But the EU leaders set convergence criteria for joining the euro that were only monetary (interest rates and inflation) and fiscal (budget deficits and debt). There were no convergence criteria for productivity levels, GDP growth, investment or employment. Why? Because those were areas for the free movement of capital (and labour) and where capitalist production must be kept free of interference or direction by the state. After all, the EU project is a capitalist one.

As I have explained in previous posts, the Marxist theory of international trade is based on the law of value. In the Eurozone, Germany has a higher organic composition of capital (OCC) than Italy, because it is technologically more advanced. Thus in any trade between the two, value will be transferred from Italy to Germany. Italy could compensate for this by increasing the scale of its production/exports to Germany to run a trade surplus with Germany. This is what China does. But Italy is not large enough to do this. So it transfers value to Germany and it still runs a deficit on total trade with Germany.

In this situation, Germany gains within the Eurozone at the expense of Italy. All other member states cannot scale up their production to surpass Germany, so unequal exchange is compounded across the EMU. On top of this, Germany runs a trade surplus with other states outside the EMU, which it can use to invest more capital abroad into the EMU deficit countries.

This explains why the core countries of EMU have diverged from the periphery since the formation of the Eurozone. With a single currency, the value differentials between the weaker states (with lower OCC) and the stronger (higher OCC) were exposed, with no option to compensate by the devaluation of any national currency or by scaling up overall production. So the weaker capitalist economies (in southern Europe) within the euro area lost ground to the stronger (in the north).

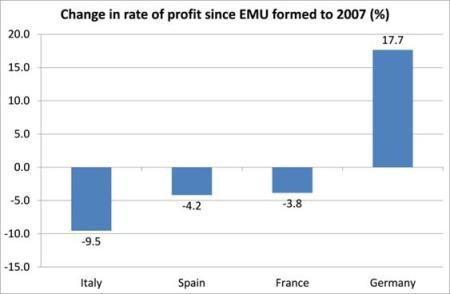

Franco-German capital expanded into the south and east to take advantage of cheap labour there, while exporting outside the euro area with a relatively competitive currency. The weaker EMU states built up trade deficits with the northern states and were flooded with northern capital that created property and financial booms out of line with growth in the productive sectors of the south. So German profitability has risen under the euro while France and the periphery have declined.

A recent paper confirms this explanation of why there is divergence, not convergence, within the Eurozone.

“The emergence of export-driven growth in core countries and debt-driven growth in the Eurozone periphery can be traced back to differences in technological capabilities and firm performance… the macroeconomic divergence between core and periphery countries is driven by the co-existence of two different growth trajectories (export-led vs. demand-driven models), which themselves can be traced back to a ‘structural polarisation’ in terms of technological capabilities.”

The authors conclude that “considering the central role of technological capabilities for the assessment of (future) economic developments, our results suggest that one cannot expect a natural convergence process to materialise in the Eurozone. It is also apparent that the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach of fiscal consolidation in the crisis-ridden periphery countries from 2010 onwards was bound to fail spectacularly… Fiscal austerity is adverse to the restoration of strong productive sectors in the Eurozone. Since structural polarisation fuels macroeconomic divergence, the Eurozone must indeed be expected to disintegrate eventually, if the ‘lock-in’ of industrial specialisation between core and periphery countries is not broken up by targeted policy interventions.”

The Italian economy has an ailing banking sector, which is far too large, holds many bad loans and has cost taxpayers many billions in recent years as a result of repeated state bailouts. There is weak productivity growth and worsening polarisation between northern and southern Italy. Far from the Eurozone providing new opportunities for Italian capital to expand, it has kept the Italian economy into a quasi-permanent smouldering crisis. While the German economy grew by an average of 2.0% in real terms and the euro area by 1.4% per year over 2010-2019, real GDP growth in Italy was only 0.2% in the same period.

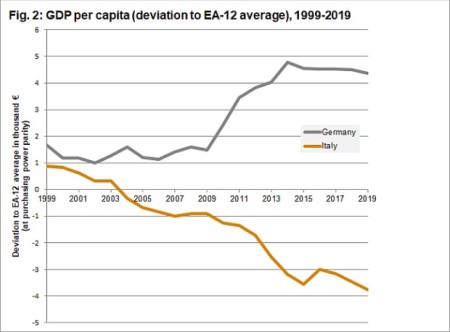

While per capita GDP (in purchasing power parities) in Italy in 1999 was still around €1000 above the Euro area average, 20 years later – just before the corona crisis began – it had fallen almost €4000 below the Euro area average. Germany, on the other hand, where per capita incomes were already slightly higher than in Italy when it joined the euro, continued to chip away over the same period, resulting in an increasing GDP per capita gap. Italy had already lost two decades in its economic development before the corona crisis.

Indeed, mutual coronabonds, so beloved of the Keynesians and post-Keynesians, is a pathetic response to this crisis. What is needed is a massive increase in the EU budget from the current ridiculously low figure of 1% of EU GDP to 20%, along with harmonised tax measures to end the ‘race to the bottom’ in taxing corporations, which Ireland leads. Such a budget could begin to plan investment, employment and public services on a huge scale to benefit all in the EU. It would be needed to finance a Marshall plan for Europe which Macron talks of, but where the useless major banks of the EU are taken over, along with the public ownership of the major sectors of productive industry. Then the basis for a real United States of Europe could be laid, where the periphery grows with the help of the core.

Without that, the coronavirus pandemic has the potential to cause an irrevocable break-up of the existing monetary union. The core countries of the Eurozone are not prepared to achieve a full fiscal union and the redistribution of resources to raise productivity and employment in the periphery. Anyway, full and harmonious development leading to convergence is not possible under the capitalist mode of production. On the contrary, the experience of EMU has been divergence.

The people of southern Europe may have to endure yet more years of austerity in paying back debt to the north. Even so, the future of the euro will probably be decided, not by the populists in the weaker states, but by the majority view of the strategists of capital in the stronger economies. The governments of northern Europe may eventually decide to ditch the likes of Italy, Spain, Greece etc and form a strong ‘NorEuro’ around Germany, Austria, Benelux and Poland. No wonder Macron is seriously worried.

No comments:

Post a Comment