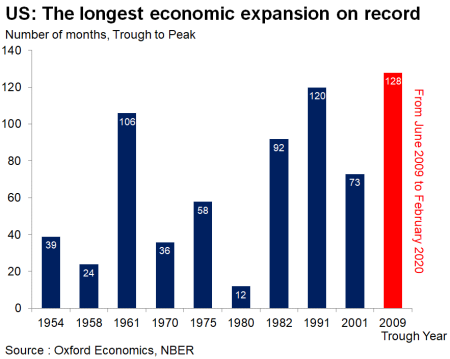

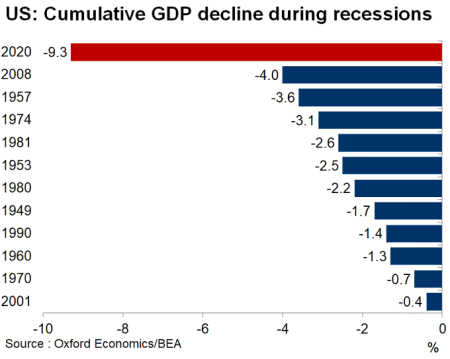

The coronavirus pandemic marks the end of longest US economic expansion on record, and it will feature sharpest economic contraction since WWII.

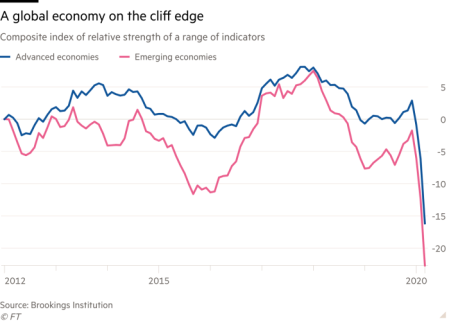

The global economy was facing the worst collapse since the second world war as coronavirus began to strike in March, well before the height of the crisis, according to the latest Brookings-FT tracking index.

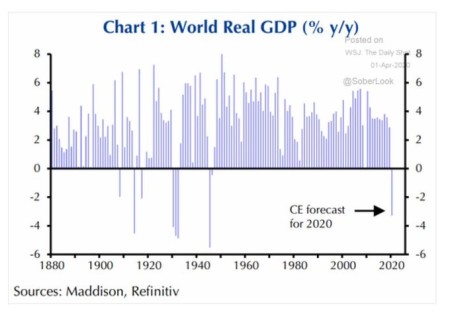

2020 will be the first year of falling global GDP since WWII. And it was only the final years of WWII/aftermath when output fell.

JPMorgan economists reckon that the pandemic could cost world at least $5.5 trillion in lost output over the next two years, greater than the annual output of Japan. And that would be lost forever. That’s almost 8% of GDP through the end of next year. The cost to developed economies alone will be similar to that in the recessions of 2008-2009 and 1974-1975. Even with unprecedented levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus, GDP is unlikely to return to its pre-crisis trend until at least 2022.

The Bank for International Settlements has warned that disjointed national efforts could lead to a second wave of cases, a worst-case scenario that would leave US GDP close to 12% below its pre-virus level by the end of 2020. That’s way worse than in the Great Recession of 2008-9.

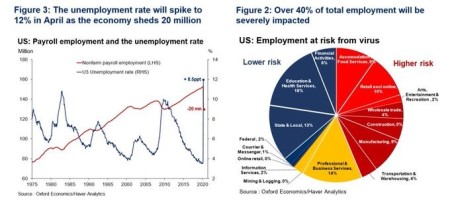

The US economy will lose 20m jobs according to estimates from @OxfordEconomics, sending unemployment rate soaring by greatest degree since Great Depression and severely affecting 40% of jobs.

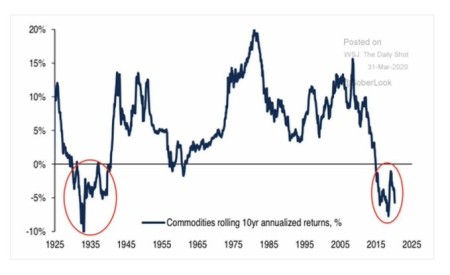

And then there is the situation for the so-called ‘emerging economies’ of the ‘Global South’. Many of these are exporters of basic commodities (like energy, industrial metals and agro foods) which, since the end of the Great Recession have seen prices plummet.

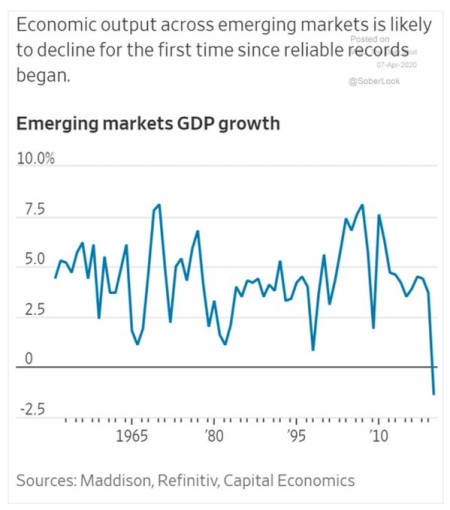

And now the pandemic is going to intensify that contraction. Economic output in emerging markets is forecast to fall 1.5% this year, the first decline since reliable records began in 1951.

The World Bank reckons the pandemic will push sub-Saharan Africa into recession in 2020 for the first time in 25 years. In its Africa Pulse report the bank said the region’s economy will contract 2.1%-5.1% from growth of 2.4% last year, and that the new coronavirus will cost sub-Saharan Africa $37 billion to $79 billion in output losses this year due to trade and value chain disruption, among other factors. “We’re looking at a commodity-price collapse and a collapse in global trade unlike anything we’ve seen since the 1930s,” said Ken Rogoff, the former chief economist of the IMF.

More than 90 ‘emerging’ countries have inquired about bailouts from the IMF—nearly half the world’s nations—while at least 60 have sought to avail themselves of World Bank programs. The two institutions together have resources of up to $1.2 trillion that they have said they would make available to battle the economic fallout from the pandemic, but that figure is tiny compared with the losses in income, GDP and capital outflows.

Since January, about $96 billion has flowed out of emerging markets, according to data from the Institute of International Finance, a banking group. That’s more than triple the $26 billion outflow during the global financial crisis of a decade ago. “An avalanche of government-debt crises is sure to follow”, he said, and “the system just can’t handle this many defaults and restructurings at the same time” said Rogoff.

Nevertheless, optimism reigns in many quarters that once the lockdowns are over, the world economy will bounce back on a surge of released ‘pent-up ‘ demand. People will be back at work, households will spend like never before and companies will take on their old staff and start investing for a brighter post-pandemic future.

As the governor of the Bank of (tiny) Iceland put it: “The money that now being saved because people are staying at home won’t disappear – it will drip back into the economy as soon as the pandemic is over. Prosperity will be back.” This view was echoed by the helmsman of the largest economy in the world. US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin spoke bravely that : “This is a short-term issue. It may be a couple of months, but we’re going to get through this, and the economy will be stronger than ever,”

Former Treasury Secretary and Keynesian guru, Larry Summers, was in tentative concurrence: “the recovery can be faster than many people expect because it has the character of the recovery from the total depression that hits a Cape Cod economy every winter or the recovery in American GDP that takes place every Monday morning.” In effect, he was saying that the US and world economy was like Cape Cod out of season; just ready to open in the summer without any significant damage to businesses during the winter.

That’s some optimism. For when these optimists talk about a quick V-shaped recovery, they are not recognising that the COVID-19 pandemic is not generating a ‘normal’ recession and it is hitting not a just a single region but the entire global economy. Many companies, particularly smaller ones, will not return after the pandemic. Before the lockdowns, there were anything between 10-20% of firms in the US and Europe that were barely making enough profit to cover running costs and debt servicing. These so-called ‘zombie’ firms may have found the Cape Cod winter the last nail in their coffins. Already several middling retail and leisure chains have filed for bankruptcy and airlines and travel agencies may follow. Large numbers of shale oil companies are also under water (not oil).

As leading financial analysts Mohamed El-Erian concluded: “Debt is already proving to be a dividing line for firms racing to adjust to the crisis, and a crucial factor in a competition of survival of the fittest. Companies that came into the crisis highly indebted will have a harder time continuing. If you emerge from this, you will emerge to a landscape where a lot of your competitors have disappeared.”

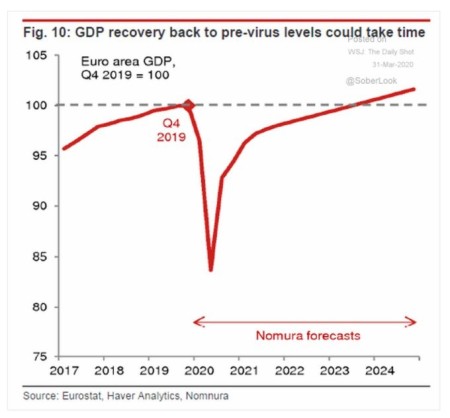

So it’s going to take a lot longer to return to previous output levels after the lockdowns. Nomura economists reckon that Eurozone GDP is unlikely to exceed Q42019 level until 2023!

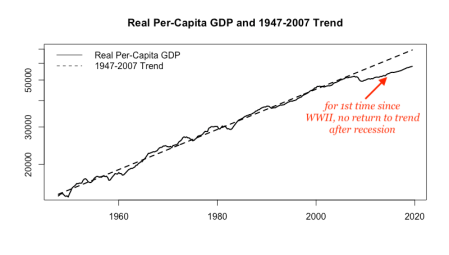

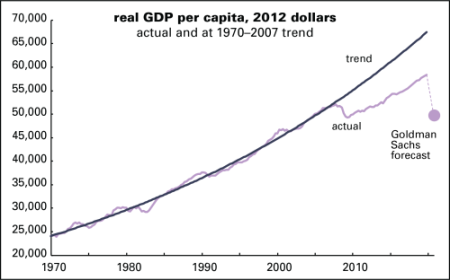

And remember, as I explained in detail in my book The Long Depression, after the Great Recession there was no return to previous trend growth whatsoever. When growth resumed, it was at slower rate than before.

Since 2009, US per capita GDP annual growth has averaged 1.6%. At the end of 2019, per capita GDP was 13% below trend growth prior to 2008. At the end of the 2008–2009 recession it was 9% below trend. So, despite a decade-long expansion, the US economy fell further below trend since the Great Recession ended. The gap is now equal to $10,200 per person—a permanent loss of income. And now Goldman Sachs is forecasting a drop in per capita GDP that would wipe out all the gains of the last ten years!

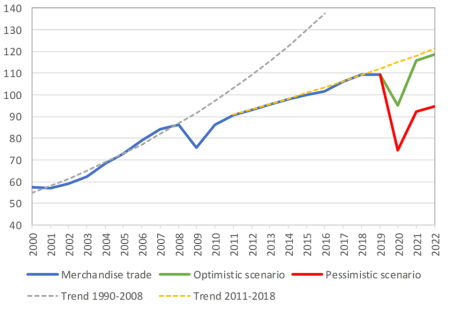

Then there is world trade. Growth in world trade has been barely equal to growth in global GDP since 2009 (blue line), way below its rate prior to 2009 (dotted line). Now even that lower trajectory (dotted yellow line). The World Trade Organisation sees no return to even this lower trajectory for at least two years.

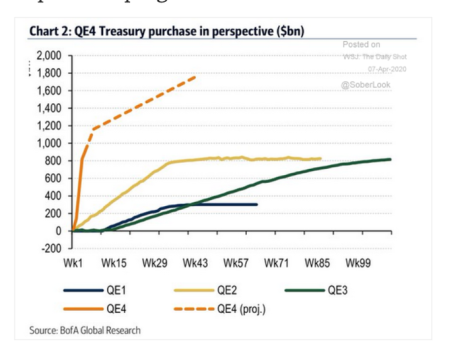

But what about the humungous injections of credit and loans being made by the central banks around the world and the huge fiscal stimulus packages from governments globally. Won’t that turn things round quicker? Well, there is no doubt that central banks and even the international agencies like the IMF and the World Bank have jumped in to inject credit through the purchases of government bonds, corporate bonds, student loans, and even ETFs on a scale never seen before, even during the global financial crisis of 2008-9. The Federal Reserve’s treasury purchases are already racing ahead of previous quantitative easing programmes.

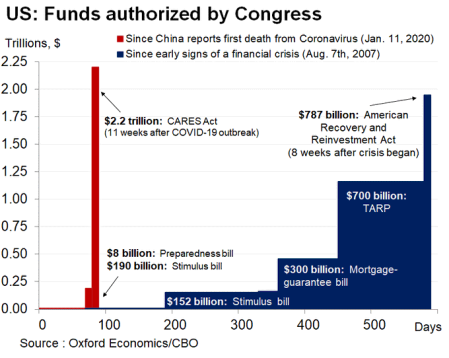

And the fiscal spending approved by the US Congress last month dwarfs the spending programme during the Great Recession.

I have made an estimate of the size of credit injections and fiscal packages globally announced to preserve economies and businesses. I reckon it has reached over 4% of GDP in fiscal stimulus and another 5% in credit injections and government guarantees. That’s twice the amount in the Great Recession, with some key countries ploughing in even more to compensate workers put out of work and small businesses closed down.

These packages go even further in another way. Straight cash handouts by the government to households and firms are in effect what the infamous free market monetarist economist Milton Friedman called ‘helicopter money’, dollars to be dropped from the sky to save people. Forget the banks; get the money directly into the hands of those who need it and will spend.

Post-Keynesian economists who have pushed for helicopter money, or people’s money, are thus vindicated.

In addition, suddenly the idea, which up to now was rejected and dismissed by mainstream economic policy, has become highly acceptable, namely fiscal spending financed, not by the issue of more debt (government bonds), but by simply ‘printing money’, ie the Fed or the Bank of England deposits money in the government account to spend.

Keynesian commentator Martin Wolf, having sniffed at MMT before, now says: “abandon outworn shibboleths. Already governments have given up old fiscal rules, and rightly so. Central banks must also do whatever it takes. This means monetary financing of governments. Central banks pretend that what they are doing is reversible and so is not monetary financing. If that helps them act, that is fine, even if it is probably untrue. …There is no alternative. Nobody should care. There are ways to manage the consequences. Even “helicopter money” might well be fully justifiable in such a deep crisis.”

The policies of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) have arrived! Sure, this pure monetary financing is supposed to be temporary and limited but the MMT boys and girls are cock a hoóp that it could become permanént, as they advocate. Namely governments should spend and thus create money and take the economy towards full employment and keep it there. Capitalism will be saved by the state and by modern monetary theory.

I have discussed in detail in several posts the theoretical flaws in MMT from a Marxist view. The problem with this theory and policy is that it ignores the crucial factor: the social structure of capitalism. Under capitalism, production and investment is for profit, not for meeting the needs of people. And profit depends on the ability to exploit the working class sufficiently compared to the costs of investment in technology and productive assets. It does not depend on whether the government has provided enough ‘effective demand’.

The assumption of the radical post-Keynesian/MMT boys and girls is that if governments spend and spend, it will lead to households spending more and capitalist investing more. Thus, full employment can be restored without any change in the social structure of an economy (ie capitalism). Under MMT, the banks would remain in place; the big companies, the FAANGs would remain untouched; the stock market would roll on. Capitalism would be fixed with the help of the state, financed by the magic money tree (MMT).

Michael Pettis is a well-known ’balance sheet’ macro economist based in Beijing. In a compelling article, entitled MMT heaven and MMT hell, he takes to task the optimistic assumption that printing money for increased government spending can do the trick. He says: “the bottom line is this: if the government can spend these additional funds in ways that make GDP grow faster than debt, politicians don’t have to worry about runaway inflation or the piling up of debt. But if this money isn’t used productively, the opposite is true.

He adds: “creating or borrowing money does not increase a country’s wealth unless doing so results directly or indirectly in an increase in productive investment… If U.S. companies are reluctant to invest not because the cost of capital is high but rather because expected profitability is low, they are unlikely to respond to the trade-off between cheaper capital and lower demand by investing more.” You can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink.

I suspect that much of the monetary and fiscal largesse will end up either not being spent but hoarded, or invested not in employees and production, but in unproductive financial assets – no wonder the stock markets of the world have bounced back as the Fed and the other central banks pump in the cash and free loans.

Indeed, even leftist economist Dean Baker doubts the MMT heaven and the efficacy of such huge fiscal spending. “It is actually possible that we could be seeing too much demand, as a burst of post-shutdown spending outstrips the immediate capacity of the restaurants, airlines, hotels, and other businesses. In that case, we may actually see a burst of inflation, as these businesses jack up prices in response to excessive demand.” – ie MMT hell. So he concludes that “generic spending is not advisable at this point.”

Well, the proof of the pudding is in its eating and we shall see. But the historical evidence that I and others have compiled over the last decade or more, shows that the so-called Keynesian multiplier has limited effect in restoring growth, mainly because it is not the consumer who matters in reviving the economy, but capitalist companies.

And there’s new evidence on the power of Keynesian multiplier. It’s not been one to one or more, as often claimed, ie. 1% of GDP increase in government spending does not lead to a 1% of GDP increase in national output. Some economists looked at the multiplier in Europe over the last ten years. They concluded that “in contrast to previous claims that the fiscal multiplier rose well above one at the height of the crisis, however, we argue that the ‘true’ ex-post multiplier remained below one.”

And there is little reason that it will be higher this time round. In another paper, some other mainstream economists suggest that a V-shaped recovery is unlikely because “demand is endogenous and affected by the supply shock and other features of the economy. This suggests that traditional fiscal stimulus is less effective in a recession caused by our supply shock. … demand may indeed overreact to the supply shock and lead to a demand-deficient recession because of “low substitutability across sectors and incomplete markets, with liquidity constrained consumers.” so that “various forms of fiscal policy, per dollar spent, may be less effective”.

But what else can we do? So “despite this, the optimal policy to face a pandemic in our model combines as loosening of monetary policy as well as abundant social insurance.” And that’s the issue. If the social structure of capitalist economies is to remain untouched, then all you are left with is printing money and government spending.

Perhaps the very depth and reach of this pandemic slump will create conditions where capital values are so devalued by bankruptcies, closures and layoffs that the weak capitalist companies will be liquidated and more successful technologically advanced companies will take over in an environments of higher profitability. This would be the classic cycle of boom, slump and boom that Marxist theory suggests.

Former IMF chief and French presidential aspirant, the infamous Dominique Strauss-Kahn, hints at this: “the economic crisis, by destroying capital, can provide a way out. The investment opportunities created by the collapse of part of the production apparatus, like the effect on prices of support measures, can revive the process of creative destruction described by Schumpeter.”

Despite the size of this pandemic slump, I am not sure that sufficient destruction of capital will take place, especially given that much of the bailout funding is going to keep companies, not households, going. For that reason, I expect that the ending of the lockdowns will not see a V-shaped recovery or even a return to the ‘normal’ (of the last ten years).

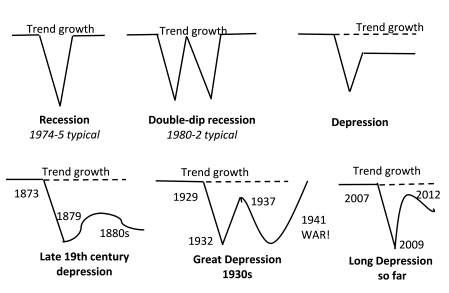

In my book, The Long Depression, I drew a schematic diagram to show the difference between recessions and depressions. A V-shaped or a W-shaped recovery is the norm, but there are periods in capitalist history when depression rules. In the depression of 1873-97 (that’s over two decades), there were several slumps in different countries followed weak recoveries that took the form of a square root sign where the previous trend in growth is not restored.

The last ten years have been similar to the late 19th century. And now it seems that any recovery from the pandemic slump will be drawn out and also deliver an expansion that is below the previous trend for years to come. It will be another leg in the long depression we have experienced for the last ten years.

No comments:

Post a Comment