As I write the coronavirus epidemic (not yet declared pandemic) continues to spread. Now there are more new cases outside China than within, with a particular acceleration in South Korea, Japan and Iran. Up to now more than 80,000 people infected in China alone, where the outbreak originated. The number of people who have been confirmed to have died as a result of the virus has now surpassed 3,200.

As I said in my first post on the outbreak, “this infection is characterized by human-to-human transmission and an apparent two-week incubation period before the sickness hits, so the infection will likely continue to spread across the globe.” Even though more people die each year from complications after suffering influenza, and for that matter from suicides or traffic accidents, what is scary about the infection is that the death rate is much higher than for flu, perhaps 30 times higher. So if it spreads across the world, it will eventually kill more people.

And as I said in that first post, “The coronavirus outbreak may fade like others before it, but it is very likely that there will be more and possible even deadlier pathogens ahead.” That’s because the most likely cause of the outbreak was the transmission of the virus from animals, where it has probably been hosted for thousands of years, to humans through use of intensive industrial farming and the extension of exotic wildlife meat markets.

COVID-19 is more virulent and deadly than the annual influenza viruses that kill many more vulnerable people each year. But if not contained, it will eventually match that death rate and appear in a new form each year. However, if you just take precautions (hand washing, not travelling or working etc) you should be okay, especially if you are healthy, young and well-fed. But if you are old, have lots of health issues and live in bad conditions, but you still must travel and go to work, then you are at a much greater risk of serious illness or death. COVID-19 is not an equal-opportunity killer.

But the illnesses and deaths that come from COVID-19 is not the worry of the strategists of capital. They are only concerned with damage to stock markets, profits and the capitalist economy. Indeed, I have heard it argued in the executive suites of finance capital that if lots of old, unproductive people die off, that could boost productivity because the young and productive will survive in greater numbers!

That’s a classic early 19th century Malthusian solution to any crisis in capitalism. Unfortunately, for the followers of the reactionary parson Malthus, his theory that crises in capitalism are caused by overpopulation has been demolished, given the experience of the last 200 years. Nature may be involved in the virus epidemic, but the number of deaths depends on human action – the social structure of an economy; the level of medical infrastructure and resources and the policies of governments.

It is no accident that China, having been initially caught on the hop with this outbreak, was able to mobilise massive resources and impose draconian shut-down conditions on the population that has eventually brought the virus spread under control. Things do not look so controlled in countries like Korea or Japan, or probably the US, where resources are less planned and governments want people to stay at work for capital, not avoid getting ill. And poor, rotten regimes like Iran appear to have lost control completely.

No, the real worry for the strategists of capital is whether this epidemic could be the trigger for a major recession or slump, the first since the Great Recession of 2008-9. That’s because the epidemic hit just at a time when the major capitalist economies were already looking very weak. The world capitalist economy has already slowed to a near ‘stall speed’ of about 2.5% a year. The US is growing at just 2% a year, Europe and Japan at just 1%; and the major so-called emerging economies of Brazil, Mexico, Turkey, Argentina, South Africa and Russia are basically static. The huge economies of India and China have also slowed significantly in the last year. And now the shutdown from COVID-19 has pushed the Chinese economy into a ravine.

The OECD – which represents the planet’s 36 most advanced economies – is now warning of the possibility that the impact of COVID-19 would halve global economic growth this year from its previous forecast. The OECD lowered its central growth forecast from 2.9 per cent to 2.4 per cent, but said a “longer lasting and more intensive coronavirus outbreak” could slash growth to 1.5 per cent in 2020. Even under its central forecast, the OECD warned that global growth could shrink in the first quarter. Chinese growth is expected to fall below 5% this year, down from 6.1% last year – which was already the weakest growth rate in the world’s second largest economy in almost 30 years. The effect of widespread factory and business closures in China alone would cut 0.5 percentage points from global growth as it reduced its main forecast to 2.4 per cent in the quarter to end-March.

Elsewhere, Italy endured its 17th consecutive monthly decline in manufacturing activity in February. And the Italian government announced plans to inject €3.6bn into the economy. IHS Markit’s purchasing managers’ index for Italian manufacturing edged down by 0.2 points to 48.7 in February. A reading below 50 indicates that the majority of companies surveyed are reporting a shrinking of activity. And the survey was completed on February 21, before the coronavirus outbreak intensified in Italy. There was a similar contraction of factory activity in France, where the manufacturing PMI fell by 1.3 points to 49.8. However, manufacturing activity increased for the eurozone as a whole in February, as the PMI for the bloc rose by 1.3 points to 49.2, but still under 50.

The US, so far, has avoided a serious downturn in consumer spending, partly because the epidemic has not spread widely in America. Maybe the US economy can avoid a slump from COVID-19. But the signs are still worrying. The latest activity index for services in February showed that the sector showed a contraction for the first time in six years and the overall indicator (graph below) also went into negative territory.

Outside the OECD area, there was more bad news on growth. South Africa’s Absa Manufacturing PMI fell to 44.3 in February of 2020 from 45.2 in the previous month. The reading pointed to the seventh consecutive month of contraction in factory activity and at the quickest pace since August 2009. And China’s capitalist sector reported its lowest level of activity since records began. The Caixin China General Manufacturing PMI plunged to 40.3 in February 2020, the lowest level since the survey began in April 2004.

The IMF too has reduced its already low economic growth forecast for 2020. “Experience suggests that about one-third of the economic losses from the disease will be direct costs: from loss of life, workplace closures, and quarantines. The remaining two-thirds will be indirect, reflecting a retrenchment in consumer confidence and business behavior and a tightening in financial markets.” So “under any scenario, global growth in 2020 will drop below last year’s level. How far it will fall, and for how long, is difficult to predict, and would depend on the epidemic, but also on the timeliness and effectiveness of our actions.”

One mainstream economic forecaster, Capital Economics, cut its growth forecast by 0.4 percentage points to 2.5 per cent for 2020, in what the IMF considers recession territory. And Jennifer McKeown, head of economic research at Capital Economics, cautioned that if the outbreak became a global pandemic, the effect “could be as bad as 2009, when world GDP fell by 0.5 per cent.” And a global recession in the first half of this year is “suddenly looking like a distinct possibility”, said Erik Nielsen, chief economist at UniCredit.

In a study of a global flu pandemic, Oxford University professors estimated that a four-week closure of schools — almost exactly what Japan has introduced — would knock 0.6 per cent off output in one year as parents would have to stay off work to look after children. In a 2006 paper, Warwick McKibbin and Alexandra Sidorenko of the Australian National University estimated that a moderate to severe global flu pandemic with a mortality rate up to 1.2 per cent would knock up to 6 per cent off advanced economy GDP in the year of any outbreak.

The Institute of International Finance (IIF), the research agency funded by international banks and financial institutions, announced that: “We’re downgrading China growth this year from 5.9% to 3.7% & the US from 2.0% to 1.3%. Rest of the world is shaky. Germany struggling to retool autos, Japan weighed down by 2019 tax hike. EM has been weak for a while. Global growth could approach 1.0% in 2020, weakest since 2009.”

What are the policy reactions of the official authorities to avoid a serious slump? The US Federal Reserve stepped in to cut its policy interest rate at an emergency meeting. Canada followed suit and others will follow. The IMF and World Bank is making available about $50 billion through its rapid-disbursing emergency financing facilities for low income and emerging market countries that could potentially seek support. Of this, $10 billion is available at zero interest for the poorest members through the Rapid Credit Facility.

This may have some effect, but cuts in interest rates and cheap credit are more likely to end up being used to boost the stock market with yet more ‘fictitious capital’ – and indeed stock markets have made a limited recovery after falling more than 10% from peaks. The problem is that this recession is not caused by ‘a lack of demand’, as Keynesian theory would have it, but by a ‘supply-side shock’ – namely the loss of production, investment and trade. Keynesian/monetarist solutions won’t work, because interest rates are already near zero and consumers have not stopped spending – on the contrary. Jon Cunliffe, deputy governor of the Bank of England, said that since coronavirus was “a pure supply shock there is not much we can do about it”.

And as British Marxist economist Chris Dillow argues, the coronavirus epidemic is really just an extra factor keeping the major capitalist economies dysfunctional and stagnating. He lays the main cause of the stagnation on the long-term decline in the profitability of capital. “basic theory (and common sense) tells us that there should be a link between yields on financial assets and those on real ones, so low yields on bonds should be a sign of low yields on physical capital. And they are.” He identifies ‘three big facts’: the slowdown in productivity growth; the vulnerability to crisis; and low-grade jobs. And as he says, “Of course, all these trends have long been discussed by Marxists: a falling rate of profit; monopoly leading to stagnation; proneness to crisis; and worse living conditions for many people. And there is plenty of evidence for them.” Indeed, as any regular reader of this blog will know.

And then there is debt. In this decade of record low interest rates (even negative), companies have been on a borrowing binge. This is something that I have banged on about in this blog ad nauseam. Huge debt, particularly in the corporate sector, is a recipe for a serious crash if the profitability of capital were to drop sharply.

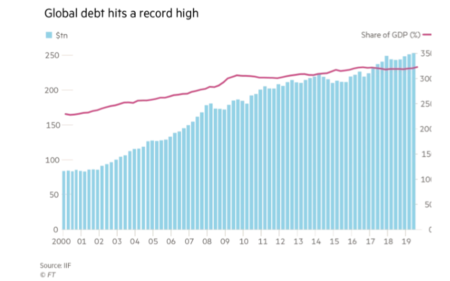

Now John Plender in the Financial Times has taken up my argument. He pointed out, according to the IIF, the ratio of global debt to gross domestic product hit an all-time high of over 322 per cent in the third quarter of 2019, with total debt reaching close to $253tn. “The implication, if the virus continues to spread, is that any fragilities in the financial system have the potential to trigger a new debt crisis.”

The huge rise in US non-financial corporate debt is particularly striking. This has enabled the very large global tech companies to buy up their own shares and issue huge dividends to shareholders while piling up cash abroad to avoid tax. But it has also enabled the small and medium sized companies in the US, Europe and Japan, which have not been making any profits worth speaking of for years to survive in what has been called a ‘zombie state’; namely making just enough to pay their workers, buy inputs and service their (rising) debt, but without having anything left over for new investment and expansion.

Plender remarks that a recent OECD report says that, at the end of December 2019, the global outstanding stock of non-financial corporate bonds reached an all-time high of $13.5tn, double the level in real terms against December 2008. “The rise is most striking in the US, where the Fed estimates that corporate debt has risen from $3.3tn before the financial crisis to $6.5tn last year. Given that Google parent Alphabet, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft alone held net cash at the end of last year of $328bn, this suggests that much of the debt is concentrated in old economy sectors where many companies are less cash generative than Big Tech. Debt servicing is thus more burdensome.”

The IMF’s latest global financial stability report amplifies this point with a simulation showing that a recession half as severe as 2009 would result in companies with $19tn of outstanding debt having insufficient profits to service that debt.

So if sales should collapse, supply chains be disrupted and profitability fall further, these heavily indebted companies could keel over. That would hit credit markets and the banks and trigger a financial collapse. As I have shown on several occasions, the profitability of capital in the major economies has been on a downward trend (see graph above from Penn World tables 9.1).

And the mass of global profits was also beginning to contract before COVID-19 exploded onto the scene (my graph below from corporate profits data of six main economies, Q4 2019 partly estimated). So even if the virus does not trigger a slump, the conditions for any significant recovery are just not there.

Eventually this virus is going to wane (although it might stay in human bodies forever mutating into an annual upsurge in winter cases). The issue is whether the ‘supply shock’ is so great that, even though economies start to recover as people get back to work, travel and trade resumes, the damage has been so deep and the time taken so long to recover, that this won’t be a quick one-quarter, V-shaped economic cycle, but a proper U-shaped slump of six to 12 months.

No comments:

Post a Comment