Stakeholder capitalism – that’s the way to ‘shape’ capitalism into something inclusive of all. That was the message of Klaus Schwab, the co-founder of the World Economics Forum (WEF), now in its 50th year with its annual jamboree in Davos, Switzerland.

Schwab was professor of business policy at the University of Geneva from 1972 to 2002. Since 1979, he has published the Global Competitiveness Report, an annual report assessing the potential for increasing productivity and economic growth of countries around the world, written by a team of economists. During the earlier years of his career, he was on many company boards, such as Swatch Group, Daily Mail Group, and Vontobel Holdings. He is a former member of the steering committee of the notorious Bilderberg group. This group has an annual conference established in 1954 to bolster a consensus among elites to support “free market Western capitalism” and its interests around the globe. These meetings are private and attended by the big players in the world.

Schwab now runs the WEF as a meeting place and think-tank for the global elite in business, government and academia to develop ideas to make capitalism work. New EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen nipped over to Davos this year to tell the gathering that “Davos is the place where conflicts are averted, business is started, disputes are finished. Thank you to Klaus Schwab for bringing together bright people and for his vision on how to shape a better future for the world.”

And what does Schwab think we want now? Stakeholder capitalism. “Generally speaking, we have three models to choose from. The first is “shareholder capitalism,” embraced by most Western corporations, which holds that a corporation’s primary goal should be to maximize its profits. The second model is “state capitalism,” which entrusts the government with setting the direction of the economy, and has risen to prominence in many emerging markets, not least China. But, compared to these two options, the third has the most to recommend it. “Stakeholder capitalism,” a model I first proposed a half-century ago, positions private corporations as trustees of society and is clearly the best response to today’s social and environmental challenges.”

So the big corporations should be ‘trustees of society’ and the main force in solving “today’s social and environmental challenges”. We need to replace ‘shareholder capitalism’ which is the dominant model right now. That’s because “the single-minded focus on profits caused shareholder capitalism to become increasingly disconnected from the real economy. Many realize this form of capitalism is no longer sustainable.” Also there is a popular reaction to the failure of ‘shareholder capitalism’ to deal with rising inequality of income and wealth, climate change and environmental disasters and the impact of new technology. Stakeholder capitalism instead, according to Schwab, can “bring the world closer to achieving shared goals”.

But what is this stakeholder capitalism? Schwab offers what he calls a Davos Manifesto. This calls for “corporations to treat customers with dignity and respect, to respect human rights throughout their supply chains, to act as a steward of the environment for future generations and, most significantly, to measure performance ‘not only on the return to shareholders, but also on how it achieves its environmental, social and good governance objectives.” In effect, then capitalism as a system of production for profit must be transformed into a system that involves other sectors of society being part of a corporate-led system of ‘shared goals’.

This smacks of the same themes presented by more radical economists and politicians who seek to modify capitalism in order to make it work for more people. There is Nobel prize winner in economics, Joseph Stiglitz, with his ‘progressive capitalism’ and then there is the Democrat presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren with her ‘accountable capitalism’. The aim in all is to find a way to ‘shape’ capitalist corporations so that they take into account all ‘stakeholders’, ie workers, customers, local councils etc – all working together. All hope that capitalists can be made to or persuaded to act to reduce inequality, create a better environment and adopt moral policies in investment. As Schwab puts it: “Business leaders now have an incredible opportunity. By giving stakeholder capitalism concrete meaning, they can move beyond their legal obligations and uphold their duty to society.”

Of course, this is disingenuous nonsense. Indeed, as Nick Buxton points out, “the profit motive will always win out.” He argues “nowhere is there a mention of enforcement mechanisms, legislation or regulation to ensure companies abide by their commitments. It is an entirely voluntary process that is completely dependent on self-regulation, which does not challenge the overriding profit-making purpose of corporations.”

At the same time as Schwab and others at Davos were talking about the mega corporations taking a lead in solving the world social problems and not just making money, US president Donald Trump turned up to tell the elite gathered there that it was great news that stock markets were hitting new highs, that capitalism was doing very well thank you, and there is no need for pessimism or talk about environmental crises or rising inequality.

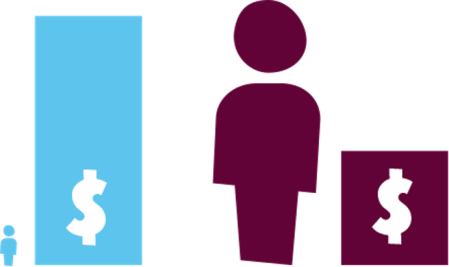

At the same time that Schwab issued his Davos Manifesto, Oxfam released its annual report on global inequality. According to Oxfam, the world’s 2153 billionaires now have more wealth than 4.6bn people who make up 60% of the world’s population. The 22 richest men in the world now have more wealth than all the women in Africa. Women and girls put in 12.5 billion hours of unpaid care work each and every day —a contribution to the global economy of at least $10.8 trillion a year, more than three times the size of the global tech industry. Getting the richest one percent to pay just 0.5 percent extra tax on their wealth over the next 10 years would equal the investment needed to create 117 million jobs in sectors such as elderly and childcare, education and health.

So much for corporate leadership in reducing inequality. And it’s same story with climate change. Average world temperatures were at record levels in 2019; and bush fires raged in extreme heat in Australia, while floods enveloped Indonesia. But the United Nations report on the current emissions gap concluded that “there is no sign of GHG emissions peaking in the next few years; every year of postponed peaking means that deeper and faster cuts will be required. By 2030, emissions would need to be 25 per cent and 55 per cent lower than in 2018 to put the world on the least-cost pathway to limiting global warming to below 2˚C and 1.5°C respectively.” As Greta Thunberg said at Davos, there is a lot of talk about dealing with climate change but little effective action.

And then there is the state of the world economy itself. While ‘shareholder capitalism’ booms, with stock markets at record highs, ‘stakeholder capitalism’ is struggling. At Davos, the IMF delivered its report on the prospects for the world economy in 2020. Chief economist IMF chief economist Gita Gopinath announced a reduction in its growth forecasts for 2020 and 2021 from the previous October estimate, while IMF boss Kristalina Georgieva warned that the global economy is at risk of a return to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Georgieva said the current world economy could be likened to the “roaring 1920s” that culminated in the great market crash of 1929. “Rising inequality and ‘increased uncertainty’ caused by the climate emergency and trade wars was “reminiscent of the early part of the 20th century – when the twin forces of technology and integration led to the first gilded age, the roaring 20s, and, ultimately, financial disaster.”

What was her answer? A more inclusive financial sector! “Financial services are primarily a good thing. Developing economies need more finance to give everyone a chance to succeed. While fiscal policy remains a potent tool, we cannot overlook financial sector policies. If we do, we may find that the 2020s are all too similar to the 1920s.” But, “It’s just that too much of a good thing can turn into a bad thing. Excessive financial deepening and financial crisis can fuel inequality. So we need to find the right balance between too much and too little.”

None of this inspires confidence in the likely success of ‘stakeholder capitalism’. No wonder a global survey released just before Davos found that over half of respondents believe capitalism in its current form does “more harm than good.” That belief was expressed by a majority across age group, gender, and income level divides. In fact, there were just six markets where the majority did not agree—Australia, Canada, the U.S., South Korea, Hong Kong, and Japan. Strongest support for the statement was found in Thailand (75 percent) and the lowest level in Japan (35 percent). In the U.S., just 47 percent agreed with the statement.

The survey also found that 48 percent of respondents believe the system is failing them, while just 18 percent believe it is working for them. Seventy-eight percent agree that “elites are getting richer while regular people struggle to pay their bills.” And in 15 of 28 markets, the majority are pessimistic about their financial future, with most believing they will not be better off in five years’ time than they are today.

Not much support for capitalism, whether shareholder or stakeholder.

No comments:

Post a Comment