“It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future” is an old Danish proverb, often attributed to Nils Bohr, the Danish atomic physicist and quantum theorist. And amusing and insightful as it may be, there is no getting away from realising that applying the scientific method to any issue requires making predictions that can be tested to support or throw doubt on a theory.

In the natural sciences, as they are called, where human beings are not being studied, prediction plays an important role. For example, according to Einstein’s theory of relativity, tit was predicted that large stellar objects will bend space itself through ‘gravitational waves’. And exactly 100 years ago, that prediction was confirmed through astronomical observation of a solar eclipse.

Applying the scientific method and making predictions in social science is clearly much more difficult because the subject being studied are human beings. Scientific method is full of pitfalls: human mistakes; inadequate data; unrealistic assumptions; inconsistent conclusions. And these pitfalls are probably greater in the social sciences, given less data and where the political and ideological pressures are greater. Nevertheless, I reckon that prediction must be part of the social scientific process.

But there is a difference between predictions and forecasts, in my view. Take the climate. We can predict that in the temperate regions of the planet, there will be four distinct seasons from spring, summer, autumn and winter. And we can predict that the sun will come over the horizon in the morning and set in the evening. Modern climate scientists are predicting that the earth is set to warm up at a rate not seen in thousands of years because of greenhouse gas emissions. Physicists predict that in about one and a half billion years, the moon will eventually break out from its orbit around the earth, producing catastrophic damage to the earth’s atmosphere and wiping out all life. We won’t be around to confirm that prediction.

Similarly, we Marxist economists can make predictions with some degree of certainty; namely that under the capitalist mode of production there will be regularly occurring crises of slumps in investment and production that cannot be avoided. We can also predict, I would claim, that the profitability of capital will fall over time as capitalism expands the productive forces and matures.

But that is not the same as making a forecast. Climate scientists cannot be sure when the earth will heat up to a tipping point that leads to uncontrollable warming that damages the fabric of the planet and engenders destructive floods, droughts etc. We don’t know in which year, decade, century or millennium when the moon will break away from the earth. We have limited ability to forecast when it is going to rain, shine or snow – although we have got much better in making such weather forecasts. And in social sciences, any forecast is even more uncertain. We cannot forecast when or how much the rate of profit will fall in any one year or the exact change in output or investment likely to be achieved in a year or month; or exactly when a new slump in production might come.

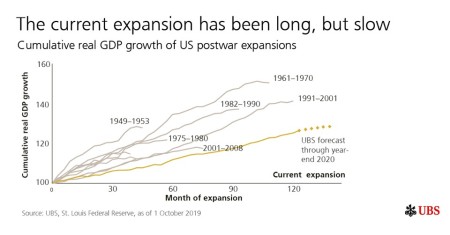

All this preamble in this post is designed to make excuses for the failure of my forecasts of a new global recession to emerge over the last few years. After the end of the Great Recession in 2009, I made a prediction that eventually there would be a new global slump. And I made a forecast that this would happen from about 2016 onwards and most likely by 2018, after all post-war recessions had come along about every 7-10 years. And yet, as we enter 2020, the world capital economy has avoided a new slump for the longest period since 1945. So how did I get my forecast wrong?

My forecast was partly based on a theory of cycles in capitalism built around the long term cycle of 55-70 years first expounded by Russian Marxist economist, Kondratiev. I reckon there have been four K-cycles since the start of the industrial revolution in Europe. The fourth cycle started in 1946, peaked in the early 1980s and should have troughed around 2018.

Marxist economist Anwar Shaikh has put forward a similar forecast to mine, also based on the dating of the K-cycle. When measured by the gold/dollar price, he forecast that the downphase in the current K-cycle would trough around 2018. More recently, Greek Marxist economists Tsoulfidis and Tsalikis (TT), in their new book, also identify long cycles. Like me, they base the up and down waves in these cycles primarily on the movement in the rate and mass of profit. However, TT reckon that the bottom of the current cycle will not be reached until 2023-28.

Cycle theory argues a new trough and slump in capitalist production is necessary to devalue the existing stock of capital before a new round of innovations based on rising profitability can begin. But forecasting when that will happen is very difficult. For the record, this is what I said at the beginning of each year since 2016, when the trough of the current cycle should have been reached. In 2016, I said: “As for 2016, I expect much the same as 2015, but with a much higher risk of new global recession appearing….even if a new global slump is avoided this year, that could be the last year that it is.” There was no slump in 2016 but the year did deliver a ‘mini-recession’ with global growth at its lowest since 2009.

Then in 2017, I said: “2017 will not deliver faster growth, contrary to the expectations of the optimists. Indeed, by the second half of next year, we can probably expect a sharp downturn in the major economies …far from a new boom for capitalism, the risk of a new slump will increase in 2017.” This forecast proved to be wrong as, instead, there was a mild recovery from the previous year in the major economies.

For 2018, I explained: “What seems to have happened is that there has been a short-term cyclical recovery from mid-2016, after a near global recession from the end of 2014-mid 2016. If the trough of this Kitchin cycle was in mid-2016, the peak should be in 2018, with a swing down again after that.” That forecast proved correct as growth slowed from mid-year 2018 and into 2019.

My forecast this time last year for 2019 was as follows: “slowing profits growth and a rising cost of (corporate) debt, alongside all the politico-economic factors of an international trade war between China and the US, suggest that in 2019 the likelihood of a global slump has never been higher since the end of the Great Recession in 2009.”

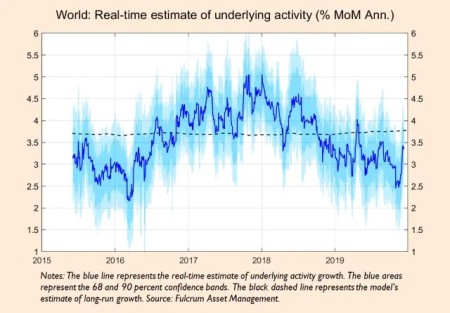

Well, there was no slump in the major economies in 2019, but they achieved the slowest rate of growth in any year since the end of the Great Recession.

So, while the decade of 2010s was the longest period without a slump in the major economies since 1945, it was also the weakest recovery from any recession in the same period.

And in 2019, global growth recorded its weakest pace since the global financial crisis a decade ago.

What were the factors for the slowdown and what are the factors that have enabled the major capitalist economies to avoid major slump that cycle theory predicts should have happened by now?

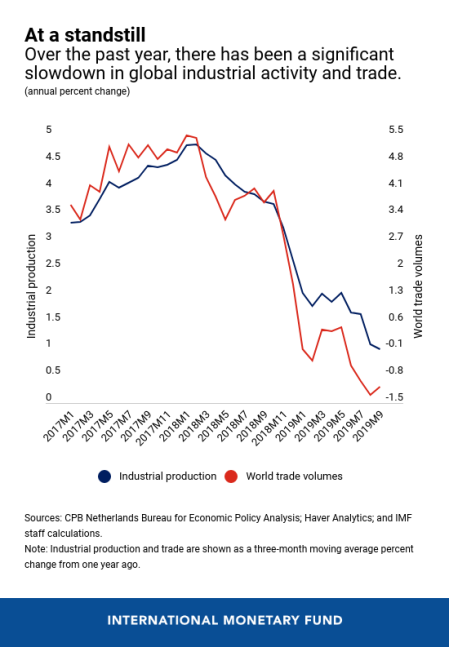

On the negative side, slow real GDP growth (of 1-2% a year) has been driven by continued low investment rates. In its recent global outlook, the IMF highlighted that: “firms turned cautious on long-range spending and global purchases of machinery and equipment decelerated.”.

The ongoing trade war between the US and China along with trade frictions with the EU was also an important factor in the slowdown in technology spending. Global trade—which is intensive in durable final goods and the components used to produce them—slowed to a standstill.

Indeed, since the end of the Great Recession, globalisation and ‘free trade’ has increasingly given way to protectionist measures, as it did in the 1930s. Since 2009, governments worldwide have introduced 2,723 new trade distortions, the cumulative effect of which was to distort 40% of world trade by November 2019.

The global trade and investment slowdown has particularly hit the so-called emerging economies, several of which have slipped into outright slumps. Emerging markets face a serious “secular stagnation” problem. Growth in almost all cases has been far lower in the last 6 years than in the 6 years leading up to the Great Recession. And in Argentina, Brazil, Russia, South Africa and Ukraine, there has been no growth at all.

Nevertheless, 2019 did not see a new global slump. Why not? First, the monetary authorities quickly reversed their previous policy stance that the global economy was fine and had ‘normalised’. In 2018, many central banks had been on hold with their policy interest rates or in the case of the Federal Reserve had hiked the rate. In 2019, the opposite was the case.

Interest rates on government bonds and other ‘safe assets’ fell back towards zero or even turned negative. With borrowing so cheap, large corporations and banks sucked up cheap credit; but not to invest in productive assets, but instead to buy up shares and bonds.

Stock market prices rocketed, up 30% in the US. Global stock markets are now worth $86trn, just shy of all-time high and equal to almost 100% of global GDP.

The main purchasers of corporate stocks are the corporations themselves. These so-called buybacks pushed up stock prices, in turn making it easier to buy out other companies or gain even more credit. Much of the buyback funds were borrowed. This expansion of what Marx called ‘fictitious capital’ has replaced investment in productive capital and it has been financed by Minsky-style Ponzi finance (ie issuing more debt to fund the cost of servicing existing debt).

The major capitalist economies are now in a fantasy world where the stock and bond markets (‘fictitious capital’) are saying that world capitalism has never had it so good, while the ‘real economy’ is stagnating in output, trade, profits and investment.

The other counteracting factor that has enabled the capitalist economies to avoid a new slump in the 2010s has been the rise in employment and the fall in unemployment. Instead of investing heavily in new technology and shedding labour, companies have sucked up available cheap labour from the reserve army of unemployed created in the Great Recession and from immigration. According to the International Labor Organization, the global unemployment rate has dropped to just 5%, its lowest level in almost 40 years.

This did not happen in the 1930s Great Depression. Then unemployment rates stayed high until the arms race and impending world war militarised the workforce. In the 2010s, it seems that companies, rather than reducing their costs in the face of recession and low profitability by sacking the workforce and introducing labour-saving technology, opted to take on labour at low wage rates and with ‘precarious’ conditions (no pensions, zero hours, temporary contracts etc). As a result, there has been a sharp increase in what are called ‘zombie companies’ that make only just enough money to pay a low-wage workforce and service their debts, but not enough to expand at all.

High employment and low real GDP growth means low productivity growth, which over time means stagnating economies – a vicious circle. The great AI/robot revolution in industry has not (yet) materialised. Globally, the annual growth in output per worker has been hovering around 2 per cent for the past few years, compared with an annual average rate of 2.9 per cent between 2000 and 2007.

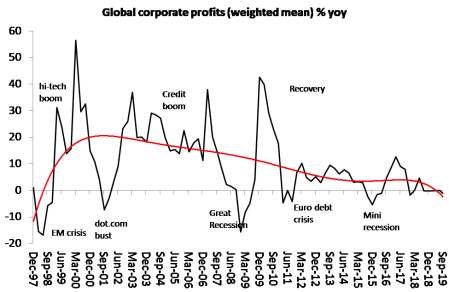

These counteracting factors may have delayed the advent of a new slump, but in my view, they can only delay it. The fundamental driver of a capitalist economy is profit – and rising profits at that. The most important factor for analysing the health of the capitalist economy remains the profitability of the capitalist sector and the movement in profits globally. That decides whether investment and production will continue. This blog has presented overwhelming evidence that profits and investment are highly correlated and in that order – see our book, World in Crisis.

Neither average profitability of capital nor the mass of profits is rising in the major economies. According to the latest data on the net return on capital provided by the EU’s AMECO database, profitability in 2020 will be 4% lower than the peak of 2017 in Europe and the UK; 8% down in Japan; and flat in the US. And profitability will be lower than in 2007, except in the US and Japan.

My estimate of global mass profits also shows, at best, stagnation. Japanese corporate profits are currently down 5% yoy, the US down 3% and Germany down 9%.

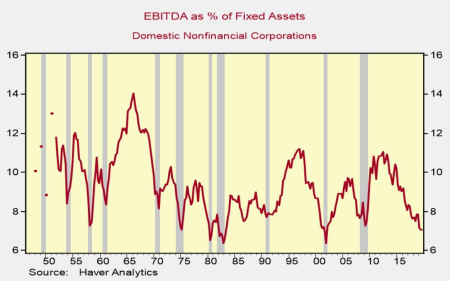

As for the largest and still leading capitalist economy in the world, the US, its rate and mass of profit have been falling since 2014. In 2018, on my measure, US overall profitability rose very slightly over 2017 (probably due to Trump’s corporate tax cuts). But profitability in 2018 was still 5-7% below the 2014 peak. If we assume real GDP, employee compensation and fixed asset growth for 2019 will have been similar to the mini-recession of 2015-16, we can expect a further significant downturn in US profitability, to levels well below 2006. On another measure, of earnings as a % of fixed assets in US non-financial companies, the rate is lower than in 2008 and approaching the all-time lows of 2001 and 1982.

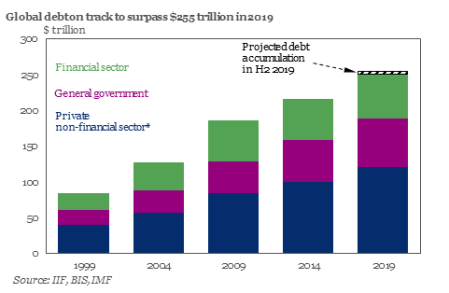

This growing profitability crisis threatens to turn the increased credit for corporations from a bonus into a burden. The Institute of International Finance estimates that global debt has now hit $250 trillion and is expected to rise to a record $255 trillion at the end of 2019, up $12 trillion from $243 trillion at the end of 2018, and nearly $32,500 for each of the 7.7 billion people on the planet.

Separately, Bank of America recently calculated that since the collapse of Lehman, government debt has increased by $30tn, corporate debt by $25tn, household by $9tn and financial debt by $2tn. The BofA warns that “the biggest recession risk is a disorderly rise in credit spreads & corporate deleveraging.”

The World Bank joined the BIS (the ‘central banks’ central bank) in warning that the largest and fastest rise in global debt in half a century could lead to another financial crisis as the world economy slows. In a report titled, Global Waves of Debt, the World Bank looked at the four major episodes of debt increases that have occurred in more than 100 countries since 1970 — the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s and the global financial crisis from 2007 to 2009. During the fourth wave, from 2010 to 2018, the debt to GDP ratio of developing countries has risen by more than half to 168%: a faster increase on an annual basis than during the Latin American debt crisis.

World Bank chief David Malpass warned that “a sudden rise in risk premiums could precipitate a financial crisis, as has happened many times in the past.” And that risk was confirmed this time last year, when interest rates rose too high – due to the attempt to ‘normalize’ policy – and stock and bond prices tumbled.

As we enter a new decade and go into the 11th year since the end of the last global slump, these are the fundamental factors that suggest a new slump is not far away. They are: stagnant or falling profits and profitability; weak or falling investment; rising corporate debt and falling trade (amid a global trade war).

But there are also counteracting factors that have so far enabled the major economies to escape a slump in production and investment (if at the price of low GDP growth, productivity and wages). Global costs of borrowing are at all-time lows, partly due to central bank policy of zero interest rates and ‘quantitative easing’; but also because there is no demand from the capitalist sector for credit to invest in productive assets or from the governments to spend. So the stock and bond markets of the world are hitting record highs. And there is the new phenomenon, not seen in previous long depressions, namely low unemployment rates that provide at least a modicum of income for households.

Mainstream economic forecasts for 2020 are generally mildly optimistic. The Fulcrum macro-model published in the FT reckons that “the outlook from the models shows global growth rates rising next year, returning roughly to trend rates. Recession risks are deemed to be low, currently standing about 5 per cent for the US and 15 per cent for the eurozone.” Alternative models, such as those from Goldman Sachs suggests a recession risk of 24 per cent in the US next year.

Maybe these forecasts will prove to be right. But eventually, the fundamental factors of profits and investment must override the counteracting factors of low interest and unemployment. Profits rule investment and investment rules employment and income, and that rules spending. The fantasy world cannot continue much longer. 2020 may be the year that it collapses.

No comments:

Post a Comment