With time and access to information, many of us could and would understand many issues more fully including what Roberts explains here so clearly in a way a worker interested in probing these ideas can understand. But even then, we can't all be experts in everything.

I urge working people to read this, think about it, read it again and discuss it. We have weekly discussions around this blog as we have stated before. If you would like to discuss this subject and it's relevance to our lives, contact us.

Years ago before I became overtly political, If I heard an academic or professor give a lecture and couldn't follow any of it I would draw that conclusion that she was brilliant. What does this say about me? I'm not an idiot. Today I have a different view; if you can't explain the general processes of an issue to me, and most thinking workers, then the weakness is yours.

Understanding how capitalism actually works, why it is the cause of and cannot solve the tragic crises affecting humanity begins with understanding the general processes at work, processes outlined here by Michael Roberts and being grounded there. Our experiences in the workplace are a plus in that regard. Once we understand this, then the building of the subjective factor, the revolutionary current within the working class, rooted in the working class, is the next step toward real freedom. Richard Mellor

Another great piece form Michael Roberts

Capital.150 part two: the economic reason for madness

The evening session of the first day of Capital.150 was about how the class struggle would ‘map out’ in the 21st century. Was Marx’s Capital still relevant in explaining where the hotspots for class battles would be concentrated?Professor David Harvey made the first contribution. David Harvey (DH) is probably the most well-known Marxist scholar in the world. A renowned academic geographer with many awards, DH has become the leading expert on Marx’s Capital and its modern relevance through many books and presentations. His website contains lectures on each chapter of Marx’s Capital and youtube is full of his presentations.

At this session, he presented his view of how class struggle, or ‘anti-capitalist’ struggle as he preferred to call it, is to be found in modern capitalism. A video of this session will soon be available but you can get the gist of what DH said from previous video presentations – the latest of which is here (his recent LSE lecture) or here on his website. DH’s thesis is also expounded in his latest book, Marx, Capital and the madness of economic reason.

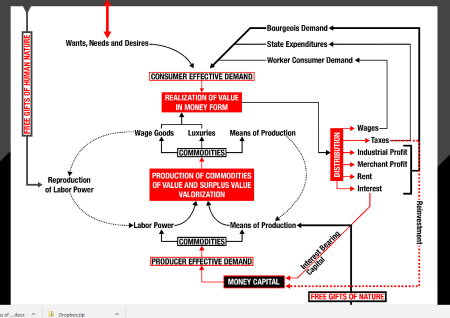

DH started with saying that capital is ‘value in motion’ – and it is a circuit of capital starting with money, then going into the production of surplus value; and then, just as important, onto the realisation of that value through sale on the market (circulation); and then onto the distribution of that realised value between sections of capitalists (industrial, landlords and finance) and to workers in wages, taxes to government.

DH likens this circuit to the geographical circuit of the planet’s water cycle – from atmosphere to sea to land and back. But the circuit of capital is not a simple cycle like that, but a spiral. It must continually accumulate and circulate and distribute ever more or it will reverse into a ‘bad infinity’ (to use a Hegelian term), spiralling down.

DH’s argues that Volume One of Capital only deals with the production part of the circuit (the production of value and surplus value). Volume Two deals with the realisation and circulation of capital between sectors in its reproduction, while Volume 3 deals with the distribution of that value. And while Marx gives a great analysis of the production part, his later volumes are not complete and have been scratched together by Engels. And thus Marx’s analysis falls short of explaining developments in modern capitalism.

You see, as DH put at his LSE lecture, production is “just a small sliver of value in motion”. The more crucial points of breakdown and class struggle are now to be found outside the traditional battle between workers and capitalists in the workplace or point of production. Yes, that still goes on but the class struggle is much more to be found in battles in the sphere of circulation (here I think DH means, for example, consumers fighting price-gouging by greedy pharma companies, the manipulation of people’s ‘wants, needs and desires’ in what they buy and think they need); and in distribution in battles over unaffordable rents with landlords or unrepayable debts like Greece or student debt. These are the new and more important areas of ‘anti-capitalist’ struggle outside the remit of Volume One of Capital. They are in communities and streets and not in the workplace. To quote DH again, the big fights are elsewhere “from the process of production”.

There are two things here: first, the theoretical and empirical basis for DH’s conclusions; and second, whether class struggle is now to be found (mainly) outside the confines of Volume One. DH provides a theoretical base to his class struggle thesis by arguing that crises under capitalism are at least as likely, if not more so, to be found in a breakdown in circulation or realisation (as DH claims Marx argued in Volume 2) than in the production of surplus value. And crises are more likely now to happen in finance and over debt due to financialisation (from Volume 3).

Well, as Carchedi showed in his paper (see my post Part One), behind financial crises lies the crises in the production of surplus value, to be found in Marx’s law of general accumulation (from Volume One) and his law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (this law is actually found in Volume 3 – thus disputing DH’s claim that Volume 3 is all about ‘distribution’).

In my view, Volumes One, Two and Three link together to give us a theory of crises under capitalism based on the drive for profit and the accumulation of surplus value in capital which falls apart at regular and recurring intervals because of the operation of Marx’s la of profitability. As Paul Mattick Snr put it back in the 1970s, “Although it first appears in the process of circulation, the real crisis cannot be understood as a problem of circulation or of realisation, but only as a disruption of the process of reproduction as a whole, which is constituted by production and circulation together. And, as the process of reproduction depends on the accumulation of capital, and therefore on the mass of surplus value that makes accumulation possible, it is within the sphere of production that the decisive factors (though not the only factors) of the passage from the possibility of crisis to an actual crisis are to be found … The crisis characteristic of capital thus originates neither in production nor in circulation taken separately, but in the difficulties that arise from the tendency of the profit rate to fall inherent in accumulation and governed by the law of value.”[i]

When you put it like that, two weaknesses spring out from DH’s schema. First, he makes no mention of the Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. He did not mention it in his presentation nor does he in his latest book. DH has already made it clear why in debates with me and others: he thinks the law is irrelevant and even wrong; and moreover (adopting the view of Michael Heinrich – also at Capital.150 – that Marx actually dropped it himself). And yet there is the law clearly expressed in Volume 3 and offering a coherent theory of regular and recurrent crises of capital that can be tested (and many scholars have done so).

And that brings me to the second weakness: crises are regular and recurrent but DH’s thesis offers no explanation for this regularity. Moreover, this regularity can be found going back 150 years since Capital was first published (and even before) without the modern role of finance or the modern manipulation of ‘wants, needs and desires’. Does this not offer a different explanation from DH’s?

For example, DH wants to tell us that crises occur because wages are squeezed down to the limit, as they have been in the neo-liberal period after the 1970s (thus a realisation of, not a production of, surplus value problem). But was the first simultaneous slump in post-war capitalism in 1974-5 due to low wages? On the contrary, most analysts (including Marxists) at the time argued that wages were ‘squeezing’ profits and that caused the slump. And most Marxists agree that this was a profitability crisis, as was the ensuing slump in 1980-2. And moreover, I have shown that when ‘social wages’ (benefits etc) are taken into account, wage share in the neo-liberal period did not fall that much, at least until the early 2000s.

Carchedi’s paper shows too that slumps have never been a result of a realisation problem (wages and government spending were always rising before each (recurrent) slump in the post-war period, including the Great Recession in 2008-9. The credit crunch and the euro debt crisis were the result of falling profitability and the switch to financial assets to raise profits, eventually leading to a financial crisis – and thus were the consequence of a crisis in the profitability of production not in its distribution.

DH reckoned capitalism worked well in the 1950s because wages were high and unions strong, presumably creating effective demand. The alternative scenario is that capitalism had a golden age because profitability was high after the war and capital could thus make concessions to maintain production and accumulation. When profitability started to fall in most of the major economies after the mid-1960s, the class battle intensified (in the workplace) and, after the defeat of labour, we entered the neo-liberal period.

That brings me to my paper, as I was the other contributor in this session (Capital.150 presentation). Here I argued that the production of surplus value and the accumulation of capital remain central to Marx’s explanation of capitalism and its contradictions that lead to recurrent crises. As Marx put it: “The profit of the capitalist class has to exist before it can be distributed.” It is not “a small sliver of value in motion” but the largest, both conceptually for Marx and also quantitatively, because in any capitalist economy, 80% of gross output is made up of means of production and intermediate goods compared to consumption.

As Engels explained, Marx’s great discovery was the existence of surplus value as the specific driver of the capitalist accumulation and labour’s immiseration. For Marx, the production of surplus-value comes first and is logically paramount, before circulation and distribution. Production and circulation are not considered by Marx as having the same explanatory power in the analysis of capitalism. Marx is clear that production is more fundamental than circulation. As Marx says, it is the production of surplus value that is the defining character of the capitalist mode of production, not how that surplus value it is circulated or distributed at the surface level.

In Volume One, Marx shows that the accumulation of capital takes the form of expanding investment in the means of production and technology while regularly shedding labour into a reserve army and thus keeping the labour content of value to a minimum. This leads to a rising organic composition of capital (the value of means of production rises relative to the value of labour power). But that very rise creates a tendency for the profitability of capital to fall over time, because value is only created by labour power.

Over history, the rate of profit in capitalism should therefore fall (despite counteracting factors). This fall will periodically lead to slumps in production and slumps will devalue and destroy capital and thus revive profitability for a while. Thus we have recurrent and regular cycles of boom and slump. But there is no permanent escape for capital. The capitalist mode of production is transient because it cannot escape from the inexorable decline in profitability due to the increasingly difficult task of producing enough surplus value.

In this sense, Capital is not so much about the ‘madness of economic reason’ but about the ‘economic reason for madness’.

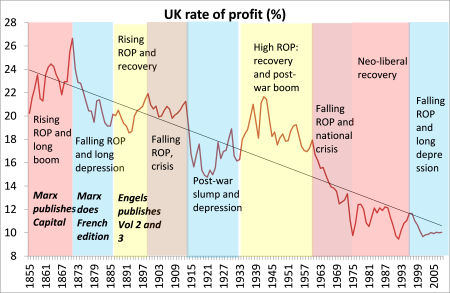

In my paper, I concentrated on Britain in the 150 years after Marx published Capital. I showed from Bank of England statistics how the overall rate of profit of British capital has fallen – not in a straight line because there were periods when the counteracting factors (a rising rate of surplus value and falling cost of technology) operated against the general tendency.

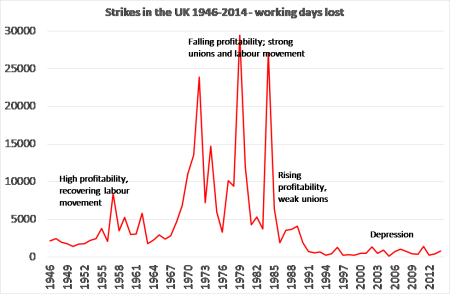

Indeed, these periods, in my view, provide crucial indicators for mapping out the intensity of the class struggle. I found, using the profitability data with the strikes data available for Britain, that whenever profitability was falling in a period when the labour movement was strong and confident then the class struggles (measured in the number of strikes) reached peaks. This was the case in Britain both prior and just after the First World War and again in the 1970s.

However, when the labour movement was defeated and weak and profitability was rising (partly as a result), as in the neo-liberal period; or when profitability was falling or low in the depressions of the 1930s and now, then the class struggle in the workplace was low too. In ‘recovery’ periods when profitability picked from lows and unions reformed (1890s and 1950s), strikes were also low but gradually rose.

Thus class struggle in the workplace was at its height when capitalist profitability started falling, but the labour movement was strong after a period of recovery. Then the best objective conditions for revolutionary change were in place.

This analysis puts the class struggle in the workplace at the centre of capitalism because it is about the struggle over the division of value between surplus value and labour’s share, as Marx intended with the publication of Volume One. This is not to deny that capitalism creates inequalities, conflicts and battles outside the workplace over rents, debt, taxes, the urban environment and pollution etc that DH focuses on, nor that the struggle does not enter the political plane through elections etc.

But none of these iniquities of capitalism can be ended without control of the means of production by working people and the ending of the capitalist mode of production (namely, production for profit of the few not the need of the many). And the working-class as a working class, not workers as consumers or debtors, remains the agency of change from capitalism to socialism. The working class (by any definition) remains the largest social force in society and globally (even defined narrowly as industrial) it has never been larger – way larger than when Marx published Capital.

‘Accumulation by dispossession’ (Accumulation by dispossession) or ‘profit from alienation’ i.e. cheating, fraud, price gouging; speculation against currencies etc, that DH puts forward as the main driver of class struggle now, has existed in many class societies before capitalism, and is thus part of capitalism too. But Marx’s Capital makes it clear that the heart of the class struggle under capitalism is the battle over the production of value, unique to capital. What happens to value is key and, in this sense, the health of any capitalist economy can be measured by the level and direction of the profitability of capital.

Capitalism has an irreversible contradiction in its ability to extract enough surplus value that brings capitalism into recurrent crises. These cannot be resolved by higher wages, more government spending or more state regulation of finance, as alternative economic theories argue. DH told us in the session that capitalism was saved in 2008 by Keynesian-type government spending measures in China. China ran up huge debts to do this and then had to export excess money capital abroad. This thesis suggests that Keynesian policies might work to avoid slumps (at least for a while) and thus there may be method in this madness of economic reason. I don’t agree and I explain why in my paper. I’ll deal with China in a future post, but in the meantime you can read what I had to say on China here.

[i] Economic Crisis and Crisis Theory. Paul Mattick 1974, https://www.marxists.org/archive/mattick-paul/1974/crisis/ch02.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment