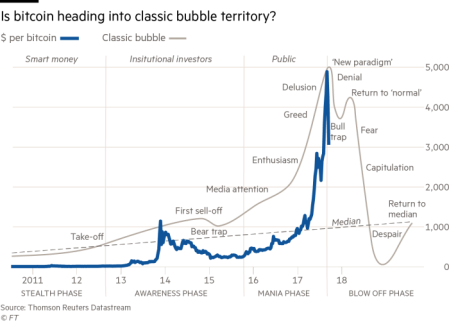

The cryptocurrency craze seems to have taken a dive in recent weeks since the Chinese authorities clamped down on speculation in the bitcoin market. The history of financial markets is littered with asset price bubbles, from tulips in the early-1600s to more recent examples, such as internet stocks in the late-1990s and US house prices before 2008. This looks like another. The ascent of the virtual currency bitcoin, which recently neared $5,000 and has risen about 350% this year, has now turned round, dropping back to $3000, if still hugely above its initial start. But it may be heading for a reckoning now.

Bitcoin aims at reducing transaction costs in internet payments and completely eliminating the need for financial intermediaries ie banks. But so far its main use has been for speculation. So is bitcoin, the digital currency that operates on the internet, just a speculative scam, another Ponzi-scheme, or is there more to the rise of all these cryptocurrencies, as they are called?

Money in modern capitalism is no longer just a commodity like gold but instead is a ‘fiat currency’, either in coin or notes, or now mostly in credits in banks. Such fiat currencies are accepted because they are printed and backed by governments and central banks and subject to regulation and ‘fiat’. The vast majority of fiat money is no longer in coin or notes but in deposits or claims on banks. In the UK, notes and coin are just 2.1% of the £2.2 trillion total money supply.

The driver of bitcoin and other rival crypto currencies has been the internet and growth of internet-based trading and transactions. The internet has generated a requirement for low-cost, anonymous and rapidly verifiable transactions to be used for online barter and fast settling money has emerged as a consequence.

Cryptocurrencies aim to eliminate the need for financial intermediaries by offering direct peer-to-peer (P2P) online payments. The main technological innovation behind cryptocurrencies has been the blockchain, a ‘ledger’ containing all transactions for every single unit of currency. It differs from existing (physical or digital) ledgers in that it is decentralized, i.e., there is no central authority verifying the validity of transactions. Instead, it employs verification based on cryptographic proof, where various members of the network verify “blocks” of transactions approximately every 10 minutes. The incentive for this is compensation in the form of newly “minted” cryptocurrency for the first member to provide the verification.

By far the most widely known cryptocurrency is bitcoin, conceived by an anonymous and mysterious programmer Satoshi Nakamoto just nine years ago. Bitcoin is not localized to a particular region or country, nor is it intended for use in a particular virtual economy. Because of its decentralized nature, its circulation is largely beyond the reach of direct regulation or monetary policy and oversight that has traditionally been enforced in some manner with localized private monies and e-money.

The blockchain’s main innovation is a public transaction record of integrity without central authority. Blockchain technology offers everyone the opportunity to participate in secure contracts over time, but without being able to avoid a record of what was agreed at that time. So a blockchain is a transaction database based on a mutual distributed cryptographic ledger shared among all in a system. Fraud is prevented through block validation. The blockchain does not require a central authority or trusted third party to coordinate interactions or validate transactions. A full copy of the blockchain contains every transaction ever executed, making information on the value belonging to every active address (account) accessible at any point in history.

Now for technology enthusiasts and also for those who want to build a world out of the control of state machines and regulatory authorities, this all sounds exciting. Maybe communities and people can make transactions without the diktats of corrupt governments and control their incomes and wealth away from the authorities – it might even be the embryo of a post-capitalist world without states.

But is this new technology of blockchains and cryptocurrencies really going to offer such a utopian new world? Like any technology it depends on whether it reduces labour time and raises the productivity of things and services (use values) or, under capitalism, whether it will be another weapon for increasing value and surplus-value. Can technology in of itself, even a technology that apparently is outside the control of any company or government, really break people free from the law of value?

I think not. For a start, bitcoin is limited to people with internet connections. That means billions are excluded from the process, even though mobile banking has grown in the villages and towns of ‘emerging economies’. So far it is almost impossible to buy anything much with bitcoin. Globally, bitcoin transactions are at about three per second compared to Visa credit at 9000 a second. And setting up a ‘wallet’ to conduct transactions in bitcoin on the internet is still a difficult procedure.

More decisively, the question is whether bitcoin actually meets the criteria for money in modern economies. Money serves three functions under capitalism, where things and services are produced as commodities to sell on a market. Money has to be accepted as a medium of exchange. It must be a unit of account with a fair degree of stability so that we can compare the costs of goods and services over time and between merchants. And it should also be a store of value that stays reasonably stable over time. If hyperinflation or spiralling deflation sets in, then a national currency soon loses its role as ‘trust’ in the currency disappears. There are many examples in history of a national currency being replaced by another or by gold (even cigarettes) when ‘trust’ in its stability is lost.

The issue of trust is brought to a head with bitcoin as it relies on “miners”, or members that contribute computational power to solve a complex cryptographic problem and verify the transactions that have occurred over a short period of time (10 minutes). These transactions are then published as a block, and the miner who had first published the proof receives a reward (currently 25 bitcoins). The maximum block size is 1MB, which corresponds to approximately seven transactions per second. In order to ensure that blocks are published approximately every 10 minutes, the network automatically adjusts the difficulty of the cryptographic problem to be solved.

Bitcoin mining requires specialized equipment, as well as substantial electricity costs and miners thus have to balance their technology and energy investment. That means increasingly bitcoin could only work as alternative replacement global currency if miners became large operations. And that means large companies down the road, ones in the hands of capitalist entities, who may well eventually be able to control the bitcoin market. Also if bitcoin were to become as viable tender to pay tax to government, it would then require some form of price relationship with the existing fiat money supply. So governments will still be there.

Indeed, the most startling obstacle to bitcoin or any other cryptocurrency taking over is the energy consumption involved. Bitcoin mining is already consuming energy for computer power more than the annual consumption of Ireland. Temperatures near computer miner centres have rocketed. Maybe this heat could be ecologically used but the non-profitability of such energy recycling may well ‘block’ such blockchain expansion.

Capitalism is not ignoring blockchain technology. Indeed, like every other innovation, it seeks to bring it under its control. Mutual distributed ledgers (MDLs) in blockchain technology provide an electronic public transaction record of integrity without central ownership. The ability to have a globally available, verifiable and untamperable source of data provides anyone wishing to provide trusted third-party services, i.e., most financial services firms, the ability to do so cheaply and robustly. Indeed, that is the road that large banks and other financial institutions are going for. They are much more interested in developing blockchain technology to save costs and control internet transactions.

As one critic of blockchain points out: “First, we’re not convinced blockchain can ever be successfully delinked from a coupon or token pay-off component without compromising the security of the system. Second, we’re not convinced the economics of blockchain work out for anything but a few high-intensity use cases. Third, blockchain is always going to be more expensive than a central clearer because a multiple of agents have to do the processing job rather than just one, which makes it a premium clearing service — especially if delinked from an equity coupon — not a cheaper one.” Kaminska, I., 2015, “On the potential of closed system blockchains,” FT Alphaville.

All this suggests that blockchain technology will be incorporated into the drive for value not need if it becomes widely applied. Cryptocurrencies will become part of cryptofinance, not the medium of a new world of free and autonomous transactions. More probably, bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies will remain on the micro-periphery of the spectrum of digital moneys, just as Esperanto has done as a universal global language against the might of imperialist English, Spanish and Chinese.

But the crypto craze may well continue for a while longer, along with the spiralling international stock and bond markets globally, as capital searches for higher returns from financial speculation.

No comments:

Post a Comment