Were the policies of so-called austerity the cause of the Great Recession? If there had been no austerity would there have been no ensuing depression or stagnation in the major capitalist economies? If so, does that mean the policies of ‘Austerian’ governments were just madness, entirely based on ideology and bad economics?

For Keynesians, the answer is ‘yes’ to all these questions. And it is the Keynesians who dominate the thinking of the left and the labour movement as the alternative to pro-capitalist policies. If the Keynesians are right, then the Great Recession and the ensuing Long Depression could have been avoided with sufficient ‘fiscal stimulus’ to the capitalist economy through more government spending and running budget deficits (i.e. not balancing the government books and not worrying about rising public debt levels).

That is certainly the conclusion of yet another article in the British centre-left paper, the Guardian. The author Phil McDuff argues that holding down wages and cutting government spending as adopted by the US and UK governments, among others, was ‘zombie economics’ “ideas that are constantly discredited but insist on shambling back to life and lurching their way through our public discourse.” Austerity was absurd economically and the article reels off a list of prominent Keynesians (Simon Wren-Lewis, Paul Krugman, Joseph Stigltiz, John Quiggin) who argue that ‘austerity economics’ was wrong (bad economics) and was really just ideology. In contrast, the Keynesians reckon that “the government does everyone a service by running deficits and giving frustrated savers a chance to put their money to work … deficit spending that expands the economy is, if anything, likely to lead to higher private investment than would otherwise materialise” (Paul Krugman).

But is it right that austerity economics is just absurd and ideological? Would Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus have avoided the Long Depression experienced by most capitalist economies since 2009?

Sure, ideology is involved. Government spending in most capitalist economies is spent not on meeting the needs of the people through healthcare, education and pensions. Much is devoted towards the needs of big business: defence and security spending; grants and credits to businesses; corporate tax reductions (while raising direct taxes on households); road building and other subsidies. So when ‘austerity’ becomes necessary, the cuts in government spending are aimed at public services (and jobs), welfare benefits etc – as these are ‘unnecessary’ costs for the capitalist sector. And yes, keeping the state sector small and reducing government intervention to the minimum is the ideology of capital. But even all this has an economic rationale.

It is an ideology that makes sense from the point of view of capital. The Keynesian analysis denies or ignores the class nature of the capitalist economy and the law of value under which it operates by creating profits from the exploitation of labour. If government spending goes into social transfers and welfare, that will cut profitability as it is a cost to the capitalist sector and adds no new value to the economy. If it goes into public services like education and health (human capital), it may help to raise the productivity of labour over time, but it won’t help profitability. If it goes into government investment in infrastructure that may boost profitability for those capitalist sectors getting the contracts, but if it is paid for by higher taxes on profits, there is no gain overall. If it is financed by borrowing, profitability will be constrained eventually by a rising cost of capital and higher debt.

Was austerity the cause of the Great Recession? Clearly not. Prior to the global financial crash in 2008 and the subsequent global economic slump, wages and household consumption were rising, not falling. And government spending growth was accelerating up to 2007 in many countries. As I have shown on many occasions on this blog, it was business investment that slumped.

To be fair, the Keynesians have not really argued that the Great Recession was a product of austerity policies. That’s because Keynesian economics never came up with a prediction before or explanation afterwards for the Great Recession. As Krugman put it in his book End the Depression Now! in 2012, there was no point in trying to analyse why the slump happened, except to say that “we are suffering from a severe lack of overall demand” – thus the slump in demand was ‘caused’ a slump in demand…. For Krugman, there was nothing really wrong with the capitalist “economic engine, which is as powerful as ever. Instead we are talking about what is basically a technical problem, a problem of organisation and coordination – a ‘colossal muddle’ as Keynes described it. Solve this technical problem and the economy will roar back into life”. If the problem is “muddled thinking” and a lack of demand, create more demand.

This gets to the crux of the Keynesian argument on ‘austerity’. If economies are suffering from a lack of demand, then cutting government spending and balancing government books when capitalists are not investing and households cannot spend is madness. Even if the Great Recession cannot be explained by Keynesian economics, it can explain the Long Depression that has followed – it’s been caused by austerity.

Now there is clearly something in the argument that when capitalist production and investment has collapsed, driving up unemployment and reducing consumer incomes, then cutting back on government spending will make things worse. And there is a growing body of empirical evidence that austerity policies in various (but not all major economies) made things worse. One paper, for example, shows that had countries not experienced ‘austerity shocks’, aggregate output in the EU10 would have been roughly equal to its pre-crisis level, rather than showing a 3% loss. For the depressed and weaker Eurozone economies of Ireland, Greece, Portugal etc, instead of experiencing an output reduction of nearly 18% below trend, the output losses would have been limited to 1%.

British Keynesian economist Simon Wren-Lewis has recently argued that the Great Recession, combined with austerity fiscal policies in the US and the UK, has had a permanent effect on output. “A long period of deficient demand can discourage workers. It can also hold back investment: a new project may be profitable but if there is no demand it will not get financed… The basic idea is that in a recession innovation is less profitable, so firms do less of it, which leads to less growth in productivity and hence supply” This is called hysteresis by mainstream economics.

But is it this lack of demand that has affected productivity growth, innovation and profitability in the Long Depression a result of austerity, or just the failure of the capitalist sector to restore profitability and investment? The usual way of trying to answer that question is to look at the multiplier effect in economics; namely the likely rise or fall in economic growth achieved from a rise or fall in fiscal spending? The trouble is that the size of this multiplier has been widely disputed. For example, the EU Commission find that the Keynesian multiplier was well below 1 in the post-Great Recession period. The average output cost of a fiscal adjustment equal to 1% of GDP is 0.5% of GDP for the EU as a whole, in line with the size of multipliers assumed before the crisis, despite the fact that approximately three-quarters of the consolidation episodes that considered occurred after 2009. So it is hardly decisive as an explanation for the continuation of the Long Depression after 2009.

So Wren-Lewis has tried to get away from the multiplier argument. Wren-Lewis defines austerity as “all about the negative aggregate impact on output that a fiscal consolidation can have. As a result, the appropriate measure of austerity is a measure of that impact. So it is not the level of government spending or taxes that matter, but how they change.” That seems a reasonable definition and yardstick to judge.

Looking at the US economy, Wren-Lewis relies on the Hutchins Center Fiscal Impact Model, which purports to show the impact of government fiscal policy on real GDP growth. He admits that the measurement is difficult, but at least the model compares changes in net government spending to growth. It shows that there was a switch to austerity from 2011 up to 2015 and this, it is argued, explains why the US economy had such slow growth and ‘recovery’ after the end of the Great Recession. If austerity had not been followed, the US economy would have made a full recovery by 2013.

Well, what strikes me first about this graph is that, according to the Hutchins Center, fiscal austerity in the US ended in 2015. But there has been no pick-up in US real GDP growth since. Indeed, US real GDP growth in 2016, at 1.6%, was the lowest annual rate since the end of the Great Recession. But maybe, Wren-Lewis would argue, is that hysteresis is now operating to keep productivity and output growth permanently low. But even if that is right, fiscal stimulus is likely to have little effect from here in getting these capitalist economies going.

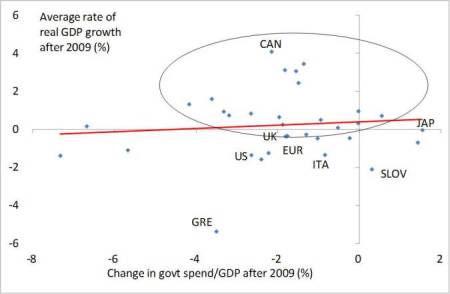

Moreover, there is plenty of evidence that fiscal stimulus will have little effect on ending the depression. Like Wren-Lewis, I have compared changes in government spending to GDP against the average rate of real GDP growth since 2009 for the OECD economies. I found that there was a very weak positive correlation and none if the outlier Greece is removed.

Another case study is Japan since 1998. I compared the average budget deficit to GDP for Japan, the US and the Euro area against real GDP growth since 1998. 1998 is the date that most economists argue was the point when the Japanese authorities went for broke with Keynesian-type government spending policies designed to restore economic growth. Did it work?

Between 1998 and 2007, Japan’s average budget deficit was 6.1% of GDP, while real GDP growth averaged just 1%. In the same period, the US budget deficit was just 2% of GDP, less than one-third of that of Japan, but real GDP growth was 3% a year, or three times as fast as Japan. In the Euro area, the budget deficit was even lower at 1.9% of GDP, but real GDP growth still averaged 2.3% a year, or more than twice that of Japan. So the Keynesian multiplier did not seem to do its job in Japan over a ten-year period. Again, in the credit boom period of 2002-07, Japan’s average real GDP growth was the lowest even though its budget deficit was way higher than the US or the Eurozone.

Now specially for this post, I have compared government spending (as defined by Wren-Lewis as government consumption plus investment, thus excluding transfers) growth with real GDP growth in the major economies. From 2010 to 2016, the average real GDP growth rate in Germany, the UK and the US was virtually the same, at about 2% a year, but government spending growth varied considerably, from 3.4% a year in (‘non-austerity’) Germany to just 1.4% a year in austerity US. The UK applied as much austerity as France but grew faster. Now it’s true that both Italy and Spain cut government spending over the period and also suffered non-existent growth, but I would venture to argue that this is more due to the failure of Eurozone fiscal integration. The core Eurozone countries have refused to help out the weaker capitalist ‘regions’ of the Euro area.

Even more convincing is the work done by Jose Tapia in comparing government spending in the US economy since 1929 against business investment and profits growth. His sophisticated regression analysis found no significant causal connection or correlation between government spending and private investment and profits. Indeed, Tapia found that “The Keynesian view that government expenditure may pump-prime the economy by stimulating private investment is also inconsistent with the finding that the net effect of lagged government expending on private investment is rather null or even significantly negative in recent decades.”

So, at the very best, the jury is out on whether Keynesian-style stimulus would get capitalist economies out of this depression. At worst, it could delay recovery in a capitalist economy.

There is a much more convincing driver of investment and growth in a capitalist-dominated economy, namely the profitability of capital, something completely ignored by Keynesian theory. I have shown in the past that real GDP growth is strongly correlated with changes in the profitability of capital (the Marxist multiplier, if you like). The Marxist multiplier was considerably higher than the Keynesian government spending multiplier in three out of the five decades, and particularly in the current post Great Recession period. And in the other two decades, the Keynesian multiplier was only slightly higher and failed to go above 1. Thus there was stronger evidence that the Marxist multiplier is more relevant to economic recovery under capitalism than the Keynesian multiplier.

Indeed, is the low productivity growth in this Long Depression caused by a permanent lack of demand or hysteresis or to low profitability? The recent annual report of the Bank for International Settlements (the research agency for global central banks) found that productivity growth had slowed down because of “a persistent misallocation of capital and labour, as reflected by the growing share of unprofitable firms. Indeed, the share of zombie firms – whose interest expenses exceed earnings before interest and taxes – has increased significantly despite unusually low levels of interest rates”.

The BIS economists come from the Austrian school that blames ‘excessive credit’ and ‘loose central bank monetary policy’ for credit-crunch slumps. But they do recognise, from the point of view of capital, that profitability is a factor behind investment, innovation and growth, rather than a ‘lack of demand’.

The policies of austerity do have an ideological motive: to weaken the state and reduce its ‘interference’ with capital. But the economic foundation of austerity was not mad or bad economics, from the point of view of capital. It aimed to reduce costs of pubic services, interest rates and corporate taxes in order to raise profitability. The Keynesian view ignores the movement of profitability as a cause of crises. And by relying on ‘demand’ as the measure of the health of a capitalist economy, Keynesian policies of fiscal stimulus fall short of solving the “technical problem” of getting the economy to “roar back into life”.

No comments:

Post a Comment