The overwhelming victory of the governing BJP in key Indian states last weekend seems to have cemented the rule of India’s prime minister Narendra Modi. In the world’s largest capitalist democracy, Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP swept the board in Uttar Pradesh state, the most populated in India with 220m voters. The BJP won 312 seats out of 403 and took just under 40% of the vote, slightly less than Modi achieved when winning the 2014 general election with the biggest parliamentary majority in 30 years.

Similarly, the Uttar Pradesh result gave the BJP the biggest majority in any state for one party since 1977. Modi’s BJP now heads the government in states where more than half of Indians live, while the Congress party, which has ruled India for most of the 70 years since independence, leads in regions covering less than 8 percent of the population.

The result came five months after the shock move last November by the Modi government to abolish high-denomination banknotes. The government claimed the aim was to flush out ill-gotten gains by rich Indians hiding their earnings in cash to avoid tax. Some Western economists like Harvard’s Larry Summers, Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen and the opposition Congress party claimed that it would squeeze credit and destroy consumer spending and lower growth.

Well, Modi appears to have been vindicated, at least by the electorate. His barbed attack on ‘Harvard University economists’ during the election campaign scored. “On one hand, there are these intellectuals who talk about Harvard, and on the other, there is this son of a poor mother, who is trying to change the economy of the country through hard work. In fact, hard work is much more powerful than Harvard.” The Hindu poor, in the rural areas particularly, where the ‘demonetisation’ was supposed to hurt the most, voted BJP. The reality is that, while many transactions are conducted ‘informally’ ie not through the banking system, most rural poor never see the sight of large bank notes. They are held by richer merchants, farmers and the urban elite to avoid paying tax. So Modi’s move was popular.

But it was not only that which gave the BJP victory. The party, formerly based on the fascist RSS, continued with its communally divisive propaganda to get people to vote on caste and religious lines. Its state leader Amit Sha promised to construct a Hindu temple on a razed mosque site and ban the slaughter of cows, worshipped by millions of Hindus.

Modi may have won the vote but the ‘demonetisation’ of 86% of circulated banknotes may still have economic repercussions. In the short term, it caused lengthy queues at ATMs, when the government failed to provide sufficient amounts of new banknotes, stalling credit and transactions, with limits placed on cash withdrawals. Those limits are only being removed next week, some five months later. The demonetisation was supposed to attack corruption and tax evasion, but it seems to have had little effect on that. Indeed, lots of rich Indians made ‘private arrangements’ to obtain new bank notes and avoid having to declare monies into bank accounts.

Two-thirds of Indian workers are employed in small businesses with less than ten workers, where labour rights are ignored – indeed most are paid on a casual basis and in cash rupees. India has the largest ‘informal’ sector among the main so-called emerging economies. Government tax revenues are low because Indian companies pay little tax and rich individuals even less. It may be that demonetisation was invoked to reduce corruption and tax scams but it was also a move that would strengthen the banking system’s control over people’s money in an undemocratic way. A completely bank accounting transaction system would put big business and the banks in the driving seat for credit and liquidity, however, more efficient. But for the rural poor, so far, that argument means little when you don’t have cash to withdraw anyway.

Modi may claim that the government’s November move has proved to have no long-term effect on the economy, but that is not true. There has been a significant fall in consumer spending and business investment that has meant India can no longer claim to be the fastest growing major economy over the likes of China. The IMF reckons that India grew 6.6% in 2016 compared with China’s 6.7% and has lowered its forecasts for this year.

Moreover, India’s figures for real GDP are to be no more trusted that those in the past provided for China, or for that matter for Ireland in the last year. Back in 2015, India’s statistical office suddenly announced revised figures for GDP. That boosted GDP growth by over 2% pts a year overnight. It seems nominal growth in national output was now being ‘deflated’ into real terms by a price deflator based on wholesale production prices and not on consumer prices in the shops, so that the real GDP figure rose by some way. Moreover, this revision was applied to the whole economic series, so nobody knows how the current growth figure compares with before 2015. Also the GDP figures are not ‘seasonally adjusted’ to take into account any changes in the number of days in a month or quarter or weather etc. Seasonal adjustment would have shown India’s real GDP growth as slowing towards the end of last year to about 5.7%, well below the official figure of 7.5%.

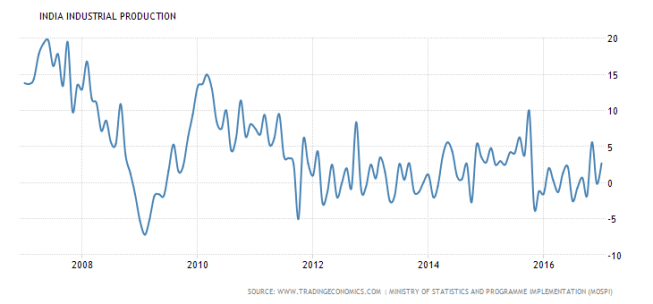

Real GDP growth may look strong on official data, but industrial output does not. India’s industrial sector is hardly growing.

Business investment is stagnating, as Indian companies are overwhelmed by large debt burdens; and these debts put a lot of pressure on the banking system. The Modi government, in contradiction with its neoliberal agenda, is trying to overcome the stagnation in business investment with government spending, but this is limited to defence and transport. Ironically, the BJP government plans to strengthen the state energy sector through mergers of its 13 state-controlled relatively small oil companies.

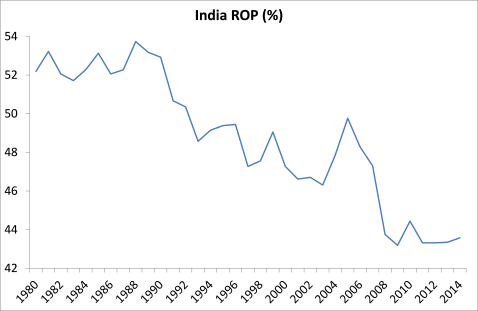

The real problem for Indian capitalism is the falling profitability of its business sector. The rate of profit is high by international standards, like many ‘emerging economies’ that have masses of cheap labour to brought in from rural areas. But, over the decades, investment in capital equipment relative to labour has started to create a reserve army of labour alongside falling profitability.

Source: Extended Penn World tables and Penn World Tables 9.0, author’s calculations.

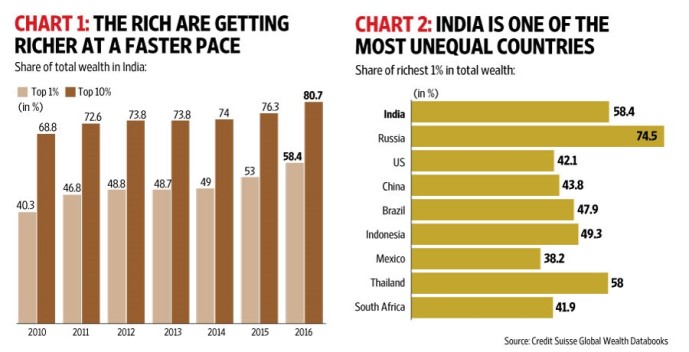

The Modi government remains optimistic that the Indian economy is going to pick up even faster this year and onwards, based on Modinomics, which boil down to privatisation, cuts in food and fuel subsidies and a new sales tax, a tax that is the most regressive way to get revenue as it hits the poor the most. The aim here, as it always is with neoliberal economic policy, is to raise the rate of exploitation of labour so that the profitability of capital is boosted and thus provide an incentive to invest, something Indian capital is refusing to do right now. Now that Modi has triumphed and look set to win the next general election in 2019, India’s big business and foreign investors will expect Modinomics to be accelerated.This can only increase inequality. Already, India is one of the most unequal societies in the world. The richest 1% of Indians now own 58.4% of the country’s wealth, according to the latest data on global wealth from Credit Suisse Group. The share of the top 1% is up from 53% last year. In the last two years, the share of the top 1% has increased at a cracking pace, from 49% in 2014 to 58.4% in 2016. The richest 10% of Indians have increased their share of the pie from 68.8% in 2010 to 80.7% by 2016. In sharp contrast, the bottom half of the Indian people own a mere 2.1% of the country’s wealth.

This inequality is not down to the Modi government alone. Previous Congress-led governments perpetuated this inequality too – indeed, under the corrupt Gandhi dynasty, made it worse. No wonder India’s poor won’t vote for the Gandhis any more. Just as in 2014, India’s electorate in the state elections were faced with a choice between a corrupt, family-run party backed by big business and landholder interests and an extreme nationalist party (with increasing backing from big business and foreign investors). For the moment, Modi wins their vote.

No comments:

Post a Comment