Mark Carney is the governor of the Bank of England. Formerly the head of the central Bank of Canada, some years ago he was headhunted to take over at the BoE on a huge salary and expenses.

This week he gave the Roscoe Lecture at Liverpool’s John Moores University, his first speech since the decision of the Brits to vote (narrowly) to leave the European Union. Carney took the opportunity to offer what his view of the state of global capitalism. And he does not make it sound good. speech946

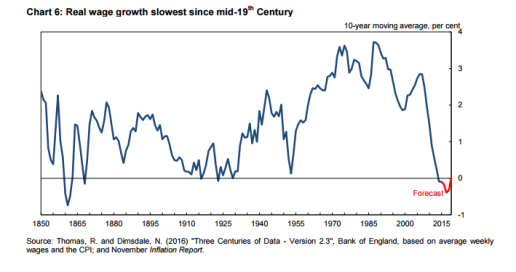

Carney pointed out that since the global financial crash of 2008, average real incomes in Britain have taken the biggest plunge since the 1860s, when “Karl Marx was scribbling in the British Library.” And “it was the poorest (who) are hit the hardest. During recessions the lower-skilled, lower paid people tend to lose their jobs first.”

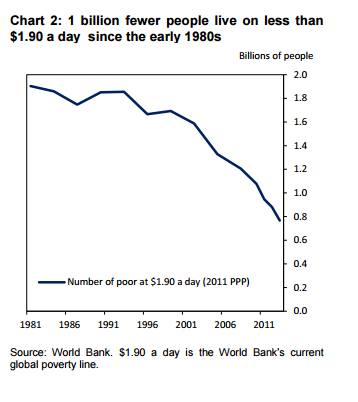

However, Carney was at pains to claim that capitalism has worked for people: “global markets and technological progress has lifted more than a billion people out of poverty, while a series of technological advances have fundamentally enriched our lives….. global markets and technological progress has lifted more than a billion people out of poverty, while a series of technological advances have fundamentally enriched our lives He added “Globally, since 1960, real per capita GDP has risen more than two-and-a-half times, average incomes have begun to converge and life expectancy has increased by nearly two decades.”

What he did not say in this praise of this record of capitalism is that the majority of that one billion lifted out of deep poverty were in China, an economy that eschews ‘free markets’ and ‘globalisation’; and goes for state investment, capital controls and the direct submission of the private sector to the regime. Life expectancy may have risen due to investment in public services and healthcare. Capitalism and free markets have played no role in that. In the ‘free markets’, most of the very poor in other countries remain poor. Indeed, the policies of the central bankers, the IMF and the World Bank in driving for ‘globalisation’ and ‘free trade’ have made the lot of these poor even worse, not better.

Per capita incomes may have risen (again mainly due to China and to a lesser extent, India, in the equation), but those incomes have not been equally increased. As Carney admitted in his speech “globalisation is associated with low wages, insecure employment, stateless corporations and striking inequalities.” In Anglo-Saxon countries, the income share of the top 1% has risen notably since 1980. Today, in the US, the richest 1% of households receive 20% of all income. Such high income inequalities are dwarfed by staggering wealth inequalities. The proportion of the wealth held by the richest 1% of Americans increased from 25% in 1990 to 40% in 2012. Globally, the share of wealth held by the richest 1% in the world rose from one-third in 2000 to one-half in 2010. And now “a typical millennial earned £8,000 less during their twenties than their predecessors.”

Carney criticised mainstream economics: “Amongst economists, a belief in free trade is totemic. But, while trade makes countries better off, it does not raise all boats; in the clinical words of the economist, trade is not Pareto optimal. Rather the benefits from trade are unequally spread across individuals and time….. Some workers, however, lose their jobs and the dignity of work, or see their “factor prices” – in plain English, wages – equalised downwards.” Perhaps Carney had been reading Marx’s scribbles after all – as this was close to scribbler’s view of free trade under capitalism – uneven and combined development.

But if capitalism has been successful over the last 50 years, according to Carney, what about the last ten? “To put it mildly, the performance of the advanced economies over the past ten years has consistently disappointed. …It doesn’t it feel like the good old days, because anxiety about the future has increased, productivity hasn’t recovered and real wages are below where they were a decade ago, something that no-one alive today has experienced before

No wonder, Carney concluded that “the public is complaining about low wages, insecure employment, stateless corporations and striking inequalities.” He admitted that mainstream economics and policies had failed the majority. “Economists must clearly acknowledge the challenges we face, including the realities of uneven gains from trade and technology”, he said.

Why have things gone so wrong? Don’t we need to know? We do, said Carney, “because any doctor knows that the importance of diagnosing the underlying causes of the patient’s symptoms before administering the cure.” Unfortunately, Carney does not know the cause: “The underlying reasons for the 16% shortfall of the UK’s productive capacity, relative to trend, are poorly understood.”

But we must try. Carney listed three priorities: “Economists must clearly acknowledge the challenges we face, including the realities of uneven gains from trade and technology” “We must grow our economy by rebalancing the mix of monetary policy, fiscal policy and structural reforms. We need to move towards more inclusive growth where everyone has a stake in globalisation.” This wish list has as much chance of surviving as the proverbial snowball in the fires of hell.

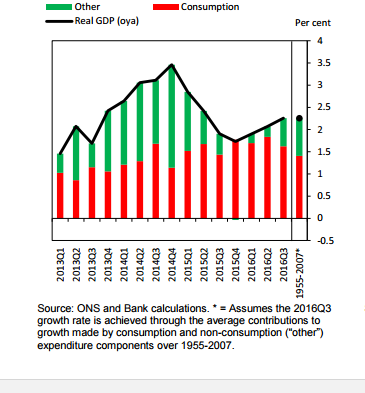

But no matter, Carney was much more concerned to convince his Liverpool audience that if it had not been for the easy money policies of the Bank under his direction, things would be even worse in the UK – although given the stats he presented, that was hardly convincing. “Monetary policy has been keeping the patient alive, creating the possibility of a lasting cure through fiscal and structural operations,” he said, adding, “monetary policy isn’t a spectre, but a friendly ghost”. But then he delivered a health warning about easy money. It leads to a consumer boom and that never provides sustained economic growth which depends on investment. “The UK expansion is increasingly consumption-led. The saving rate has fallen towards historic lows and borrowing has resumed. Evidence from the past quarter century across a range of countries suggests episodes of consumption-led growth tends to be both slower and less durable. This is because consumption growth eventually outpaces earnings growth, increasing debt and making demand more sensitive to changes in employment and income.” The relative boom in the British economy (ie 2%-plus economic growth) won’t last.”

It was up to governments now to turn things round. But given that Carney and his bank economists did not know why things had got so bad, he offered no real advice to governments on how to get productivity up, inequality down and real incomes restored.

Next year is the 150th anniversary of the publication of Marx’s Capital Volume One, the product of the ‘scribblings’ that Marx was making in the British Museum in the 1860s. Perhaps Carney should have read them to see why things are so bad and what to do about it.

No comments:

Post a Comment