The legacy of the global financial crash and the Great Recession has left a huge mound of debt globally that weighs down the world capitalist economy. This debt is a major factor, along with the low level of profitability of capital in the major economies and is generating what I call the Long Depression since 2009. Global growth has been well below pre-crisis trends and world trade growth has ground to a halt.

If companies face low profitability on their investment and still have high debts to repay or service, they will be reluctant to invest more. If governments are burdened with high debts as a result of bailing out the banks and because unemployment and social security benefits stay high, then governments cut public investment. If households are still burdened with large mortgages, they won’t spend more, but save. All this adds up to weak investment and low wage and employment growth.

The only saving grace is that central banks have driven global interest rates down towards zero (or even negative), so that servicing debt is cheap and cheap credit can be used by corporations to buy back shares, pay out dividends and speculate in bond and stock markets; for governments to service their bonds and borrow more; and for households to pay their mortgages and run up credit card debt. But the global debt hangover has not gone away and if interest rates should start to rise or if economies should drop into recession or deflation, this debt burden could turn into a spiral of collapse.

That is what is worrying the international economic agencies like the IMF or the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). The IMF has just reported that global debt is at a record high. Excluding the banking sector, non-financial sector (corporations, households and governments) debt has more than doubled since the turn of the century, reaching $152 trillion last year, and it’s still rising. If you include the banking sector, McKinsey finds that the total debt reaches $200 trillion.

Current debt levels now sit at a record 225% of world GDP, with about two-thirds of that in the private sector (household mortgages and corporate borrowing). The IMF says that slow global growth (the Long Depression in other words) is making it difficult to pay off the obligations, “setting the stage for a vicious feedback loop in which lower growth hampers deleveraging and the debt overhang exacerbates the slowdown.” IMF fiscal chief, Vitor Gaspar, warned that “excessive private debt is a major headwind against the global recovery and a risk to financial stability.”

The IMF laid out the major risks to the financial system. First, European banks are facing a chronic profitability crisis. Many haven’t been able to clear the legacy debt off their balance sheets and investors are increasingly sceptical they’ll be profitable based on their current structures.

This potential banking crisis has been exposed by the debacle of Deutsche Bank, Germany’s largest bank by far in Europe’s most successful economy. Facing massive fines from the American Justice department for ‘mis-selling’ mortgage bonds to clients globally during the great housing boom and bust leading to the global financial crash, Deutsche has been pushed close to the edge and may have to be bailed out by more public money. Last summer, the IMF did a report on German banks and concluded that “Deutsche Bank appears to be the most important net contributor to systemic risks in the global banking system,” followed by HSBC and Credit Suisse. Deutsche has $47trn in notional value of derivatives outstanding. In other words, because it is so big, if it goes down, it will take many other banks with it.

At the same time, Italy’s banks have over €200bn in bad loans on their books from companies which cannot service their debts because of the very weak Italian economy and slow global growth. Italy’s third biggest and oldest bank, Monte Paschi, is bust and has already had two bailouts. And then there are the Portuguese banks, the largest of which, Espirito Santo,like Monte Paschi, had to be bailed out to avoid a systemic crisis.

Second, there is rising corporate debt, particularly in so-called emerging markets. The combined shock of the commodity-price plunge and China’s slowdown has made the surge in private debt a major threat to emerging-market economies.

Investment bank JP Morgan reckons that the debt of non-financial corporations in emerging economies has surged from about 73% of GDP before the financial crisis to 106% of GDP. This 34%-point increase is enormous, averaging nearly 5%-points per year since 2007. In previous research, the IMF has found that an increase in the ratio of credit to GDP of 5%-points or more in a single year signals a heightened risk of an eventual financial crisis. Many emerging market economies have registered such an increase since 2007. Hence the conclusion of the credit analysts, S&P, that “we have reached an inflexion point in the corporate credit cycle”.

The policy answer of the economic authorities in the major economies to the Long Depression has been to tighten government spending and try to reduce deficits on government budgets to get the public debt burden down, while central banks cut interest rates and print money by the trillions to create cheap money to pay debts and invest.

But fiscal ‘austerity’ and cheap money have not worked anywhere to get the world economy going. Zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) has given way to negative interest rate policy (NIRP) and quantitative easing (QE) or printing money to give to the banks is giving way to the idea of ‘helicopter money’ (printing money to give directly to governments or even households). But it is not doing the trick, because this credit just builds up in banks and in speculative financial investment as profitability in productive sectors remains too low to encourage new investment and consequently growth.

Now international agencies like the IMF and the OECD and Keynesian economists are calling for ‘fiscal action’. The big call is for ‘infrastructure investment’, i.e. using government funds to build roads, bridges, communications etc. This would boost investment and employment and get economies going, it is argued. As I have said before, such investment would undoubtedly help but it would have to be huge to have much of an impact. The G20 economies represent 92% of the world economy and in 2014 G20 ministers agreed to raise annual growth by an extra $2trn (without specifying how!). But even if it were done by more infrastructure investment, it would not work. As the chair of JP Morgan, the US investment bank put it: “I would put quantitative targets on things that are under governments’ control, and national GDP growth is not,” Dr Frenkel said. “As much as you’d like to jump 5 metres without a pole you will not be able to.”

Investment by the capitalist sector is seven or eight times larger than government investment in most major economies (China and India excepted). A 1% of GDP increase in government investment sounds large at around say $1trn globally, but it is really a pinprick compared to the annual global investment of close to $20trn.

And anyway, the willingness of governments to initiate such spending is capped by the need to keep control of rising public debt. Public debt is now around 85% of world GDP, according to the IMF data, with no sign of any decline. Only very low interest rates are making it possible to service this debt without even more stringent fiscal ‘austerity’ (government spending cuts and tax rises). A large increase in government investment will drive debt up further, at least to begin with.

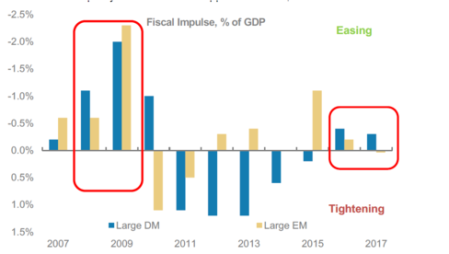

So governments are not doing what the Keynesians (outside and inside the IMF) want. Indeed, the IMF forecasts that budget balances will tighten not relax in both advanced and emerging markets next year. Morgan Stanley, the American investment bank, reckons that the governments of the advanced economies will ease fiscal policy next year but only by 0.3% of GDP — equating to a mild $115 billion increase in spending – nowhere near $1trn or $2trn. “Fiscal easing equivalent to 0.3% of GDP is unlikely to materially increase global growth,” said Elga Bartsch, lead author of the Morgan Stanley report.

The global debt hangover remains and the alka seltzer of cheap and plentiful credit has not cured it. The alternative of fiscal spending won’t work either and won’t be enough anyway. The mainstream economics of monetarism and Keynesianism cannot get rid of this hangover because the world capitalist economy is still drunk from too much debt and starved of profitability.

And now total corporate profits are falling globally while debt continues to rise – with the prospect of a new global slump on a fast-approaching horizon.

No comments:

Post a Comment