The EU and Canada finally signed the CETA free trade deal on Sunday that was almost derailed last week by objections from French-speaking Belgians, exposing the difficulties of securing new global trade agreements. The Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) deal between Asia and the US was agreed earlier this year, but still needs to be ratified by the assemblies of all the signatory states. And both candidates in the US presidential election are now opposed to ratification. The TransAtlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) deal between Europe and the US remains on hold with little likelihood of an agreement for the foreseeable future.

Supporters of Ceta say it will increase Canadian-EU trade by 20% and boost the EU economy by €12bn a year and Canada’s by C$12bn. But we have heard of such benefits from global trade agreements before and they always turn out to be much less, especially for the weaker partners in any deal.

Moreover, CETA was signed but only because it was agreed that the most controversial parts of CETA would be put on ice, namely the reduction of tariffs on Canadian farm goods that threatened Wallonia’s farmers and the so-called investment disputes courts that would enable corporations to sue governments for any action that threatened their profits (through courts with corporate representatives!). It may now take another two years before full ratification by all 28 EU member states is completed.

As I have argued before, these regional bloc deals have replaced all encompassing world deals through the World Trade Organisation (WTO) because global deals have failed time after time since the global financial crash. And the reason is clear. It’s because world trade growth has slowed to a stop. When a cake gets larger and larger, those cutting it up are happy to reach an agreement to share. But when a cake starts to get smaller, people don’t want to give up their piece and share. That’s the situation now. The Long Depression with its low real GDP growth rate and no inflation in prices of commodities has shrunk the cake.

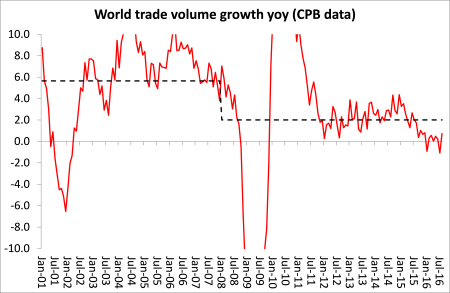

The WTO recently cut its forecast for global trade growth this year by more than a third. It now expects just 1.7% growth in trade volume for 2016, down from its previous estimate of 2.8%. The WTO now expects slower 2017 trade growth too than in its previous forecast, with a rise of 1.8-3.1% rather than the 3.6% it had estimated in April.

As I have pointed out before, since the end of the Great Recession, instead of world trade growth outstripping world real GDP growth by some margin, the reverse is now the case. On average, since 1945, world trade used to grow 1.5 times faster than GDP and even twice as fast when ‘globalisation’ picked up in the 1990s. On WTO estimates, trade will grow only 80% as fast as the global economy from now on, the first reversal of globalisation since 2001 and only the second since 1982.

Even the WTO’s forecasts look optimistic. The Dutch economic trade agency CPD finds that through August 2016, world trade volume was actually flat. And if we look at the record of world trade growth since the Great Recession, annual average growth in volume has been only 2% compared to 5.6% before 2008.

The US is no exception to the broader trend. The total value of American imports and exports fell by more than $200 billion last year. Through the first nine months of 2016, trade fell by an additional $470 billion. It is the first time since World War II that trade with other nations has declined during a period of economic growth.

All this seriously worries the strategists of capital, especially those representing the major economies. “Curbing free trade would be stalling an engine that has brought unprecedented welfare gains around the world over many decades,” Christine Lagarde, IMF managing director, wrote in a recent call for nations to renew their commitment to trade.

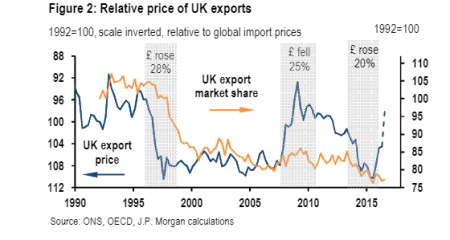

All this makes the prospects for British capital getting a good deal on trade with the EU in the next two years of negotiation look dismal. And as I have argued before, the idea that UK exporters will gain more market share after the 20% devaluation of the pound will prove false. Following the 25% depreciation in sterling after the Great Recession in 2008, UK exporters failed to get an increase in market share. Then, as the currency rose in 2013, export share fell back even further.

The reason was two-fold. British export companies preferred to get more profits and so kept up export prices even as sterling fell. But also devaluation meant rising import prices and much of the inputs for British exports (cars or financial services) are imported. So higher import prices made it difficult to lower export prices.

World trade has stopped growing. Regional trade agreements are in jeopardy. Globalisation is over. A good time for Brexit.

No comments:

Post a Comment