This is a big week for the central banks of the major economies. The US Federal Reserve meets on Wednesday to decide on whether to resume its planned series of hikes in its policy rate that sets the floor for all interest rates domestically and often internationally. On the same day, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) must decide whether to resume its negative interest rate policy (NIRP) by going even deeper into negative territory on its policy rate.

While both central banks appear to be going in different directions (one raising interest rates because it wants to ‘control’ a budding economic recovery and the other lowering rates in order to ‘stimulate’ a stagnant economy) in reality both banks are in a similar position. Their reason for existence and the credibility of their strategies are in serious jeopardy.

The reality is that despite nine years of holding rates (until last December) by the Fed and despite cuts and negative rates by the BoJ, along with massive credit injections by both into the banking system through ‘quantitative easing’ (buying government and corporate bonds with the creation of new money), the economies of the US and Japan have failed to recover to anything like the trend growth in real GDP (and per capita) that was achieved before the Great Recession of 2008-9.

In effect, monetary policy as a weapon for economic recovery has miserably failed. The members of both the US Fed and BoJ monetary committees are divided on what to do. The Fed’s chair Janet Yellen reckoned at the beginning of this year that the US economy was on the road to achieving trend growth and full employment. But the latest data on the economy make dismal reading.

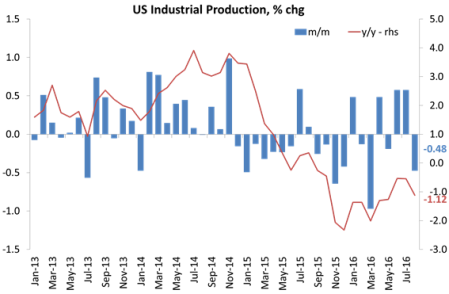

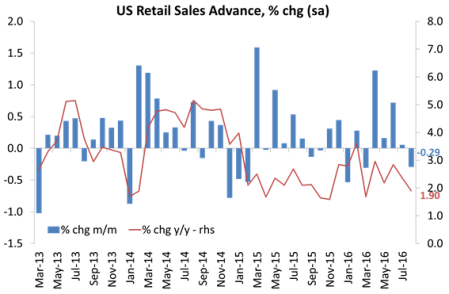

Not only has the real GDP rate slowed to near 1% with industrial production falling, but now even retail sales growth, an indicator of consumer spending and a key plus up to now for the US recovery, has dropped back (at only +0.8% yoy after inflation is deducted).

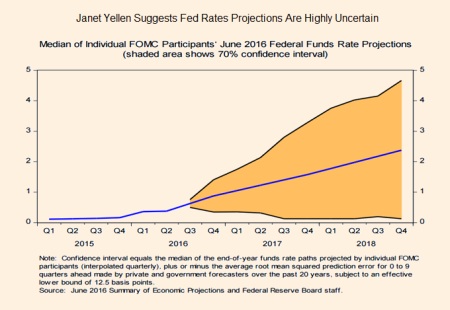

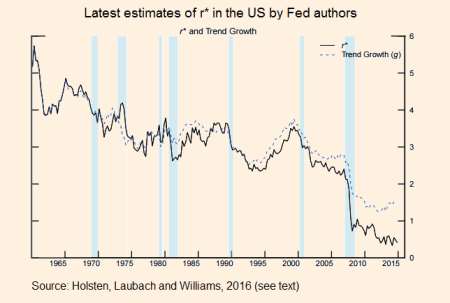

The Fed has been following a monetary policy theory that there is some ‘equilibrium’ rate of interest that can be identified that would be appropriate for an economy to be back at trend growth and full employment without serious inflation. The Fed calls this (imaginary) rate, R*. This idea is based on the theory of the neo-classical economist Kurt Wicksell. The trouble is that it is nonsense – there is no equilibrium rate. Even worse, the Fed’s economists have no idea what it should be anyway. In their latest projection, they reckon R* is anywhere between 1% and 5% for two years ahead, with a best guess at about 2%. The current Fed rate is 0.5%.

And because the US economy has failed to get back towards pre-crisis trend growth, the Fed’s economists keep revising down that estimate.

It’s the same with the BoJ. Their economists have no idea what policy rate to set in order to kick-start the economy and get Japan out of a deflationary environment. That is why they are conducting a ‘full review’ of monetary policy to be discussed at their meeting this week.

It’s clear that monetary policy has failed. As this was a major plank of so-called Abenomics in Japan (and strongly promoted by American monetarist Ben Bernanke and Keynesian Paul Krugman), there should be egg on many faces. The response of the mainstream economists has been to look for even more extreme measures of monetary easing: NIRP is one, helicopter money is another.

Keynesian economic journalist Martin Wolf has been calling for helicopter money. You see, R* is not really anywhere near as high as the Fed economists think. The major economies are in a state of ‘secular stagnation’ caused by ageing, slowing productivity growth, falling prices of investment goods, reductions in public investment, rising inequality, the “global savings glut” and shifting preferences for less risky assets. If we recognise that R* is really low, then we can adopt the policy of handing out cash to companies and individuals directly and combine that with more public spending (with larger government budget deficits) on investment projects – something advocated by many Keynesians, like Larry Summers.

But these answers are really an admission of the failure of monetarism and monetary policy, something that Marxist economics could have told the mainstream (and some did) years ago. Mainstream economics (like Wolf above) still fails (or refuses) to recognise what Marxist economics can explain: the capitalist economy does not respond to injections of money (or, for that matter, injections of government spending) but to the profitability of investment. The rate of profit on capital invested is the best indicator for investment and growth, not the rate of interest on borrowing. It is r, not R*, that matters.

I and other Marxist economists have spelt this out both theoretically and empirically over several years. But it is not only Marxist economists. Mainstream academic economics may ignore profits as a key driver of investment and growth, but economists in investment banks (who have the money and profits for investors on the line) have started to recognise it.

First, there was Goldman Sachs, even if its analysis was locked into a neoclassical marginalist approach. Then there was JP Morgan. In a recent repprt, JP Morgan economists reckon that business investment and profits are closely correlated – “both business confidence and profit growth are highly statistically significant in explaining capital spending.” JP Morgan reckons that business spending “is less a function of borrowing costs than of an assessment of the outlook and profitability. On balance, this model explains 70-85% of the variation in business equipment spending growth”.

Now there is Deutsche Bank. Deutsche Bank’s economists have noticed that “Profit margins always peak in advance of recession. Indeed, there has not been one business cycle in the post-WWII era where this has not been the case. The reason margins are a leading indicator is simple:When corporate profitability declines, a pullback in spending and hiring eventually ensues.”

From Q3 2014, when profit margins peaked, to Q1 2016, domestic profits have declined by a little over -$175 billion. Not surprisingly, the decline in profit growth has occurred alongside a deceleration in domestic demand.

As Deutsche points out, the year-over-year growth rate of real final sales to private domestic purchasers, “our favorite indicator of underlying demand”, peaked at 3.6% in Q4 2014 and has since slowed to 2.6% as of last quarter. Deutsche goes on: “With that in mind, the historical data reveals that the average and median lead times between the peak in margins and the onset of recession are nine and eight quarters, respectively, which, as DB concludes, “would imply that the economy could enter recession as soon as the second half of this year.”

No comments:

Post a Comment