The weekend meeting of the heads of state of the top 20 economies in the world (G20) in the Chinese resort of Hangzou concluded that the global economy was still in trouble. The IMF reckoned 2016 would be the fifth consecutive year in which global growth was below the 3.7% average recorded in the period from 1990 to 2007.

And just before the G20 summit, the IMF issued a report forecasting even slower growth than that rate. “High frequency data points to softer growth this year, especially in G-20 advanced economies, while the performance of emerging markets is more mixed”. It went on: “The global outlook remains subdued, with unfavorable longer-term growth dynamics and domestic income disparities adding to the challenges faced by policymakers. Recent developments—including very low inflation, along with slowing investment growth and trade—broadly confirm the modest pace of global activity. The decline in investment, exacerbated by private sector debt overhangs and financial sector balance sheet issues in many countries, low productivity growth trends, and demographic factors weigh on long-term growth prospects, further reducing incentives for investment despite record-low interest rates. A period of low growth that has bypassed many low-income earners has raised anxiety about globalization and worsened the political climate for reform. Downside risks still dominate.”

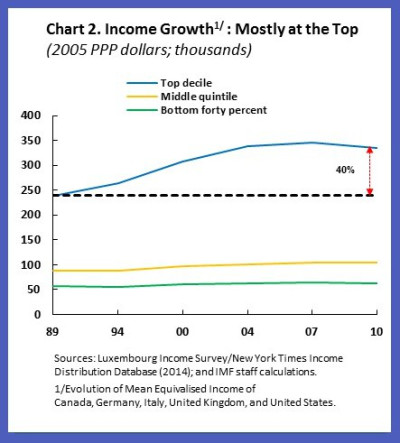

IMF chief, Christine Lagarde, also blogged that “Weak global growth that interacts with rising inequality is feeding a political climate in which reforms stall and countries resort to inward-looking policies. In a broad cross-section of advanced economies, incomes for the top 10 percent increased by about 40 percent in the past 20 years, while growing only very modestly at the bottom. Inequality has also increased in many emerging economies, although the impact on the poor has sometimes been offset by strong general income growth”.

Low growth, high debt, weak productivity and rising inequality: that’s the story of the world economy since the end of the Great Recession in 2009.

What did the IMF suggest to the G20 leaders as way out of this depressed activity? First, more “demand” support. But monetary policy (zero or negative interest rates and printing money) was not working. So it was “time to boost public investment and upgrade infrastructure”. But the world needs more neo-liberal type ‘structural reforms’, like deregulation of labour and product markets, reducing pension schemes etc, in order to boost profitability. But there should also be less inequality through higher basic benefits and increased education for low-wage earners. So we need more globalisation, world trade, neoliberal reforms and less inequality. Reconcile those!

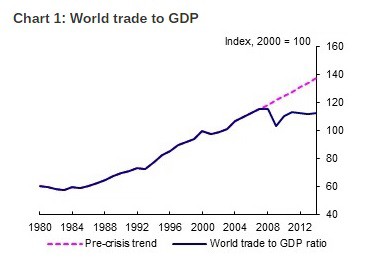

One idea that dominated the G20 meeting was the need to boost world trade and support ‘globalisation’. As this blog has reported often, world trade growth has been dismal and is a big feature of the Long Depression since 2009.

But worse for global capitalism, and American imperialism in particular, there has been a growing trend away from ‘globalisation’ (free trade of goods, services and capital flows for big business). The World Trade Organisation trade agreements have stopped and the regional mega-deals like TTP and TTIP are in serious jeopardy. Everywhere, governments are under pressure to block further deals and even reverse them (eg Trump on NAFTA). So Lagarde called for renewed support for globalisation and the neo-liberal era now under attack.

The Chinese were particularly worried because global trade growth is vital to its export, investment-led economic model. Chinese President Xi Jinping was vocal in a call for wider trade and investment. “We should turn the G20 group into an action team, instead of a talk shop,” he said.

Meanwhile, optimism that a proper world economic recovery remains. Gavyn Davies in the FT has recently been claiming that his Fulcrum forecasting agency was finding a world economic pick-up. However, this weekend, he was slightly less sanguine. “In August, we have received no confirmation that a cyclical upswing is gaining momentum. But nor has there been a significant decline in activity: the jury is still out”.

At the beginning of the year, many mainstream economists reckoned that China and other ‘emerging’ economies were going south and would drag the rest of the world down with them. I disagreed at the time. The optimism for recovery then switched to the US and even Europe.

However, as we move into the last part of 2016, it has become clear that the US economy has slowed down even more and Europe has achieved hardly any pick-up at all. So now the optimism has swung back to the major emerging economies. As the UK’s accountancy firm Deloitte economists put it today: “The downward trend for emerging market activity seems to have run its course. Growth is widely expected to accelerate in 2017. India is forecast to grow by 7.6% next year, the fastest rate of growth among any major economy. Brazil and Russia are likely to emerge from recession. Chinese growth is expected to ease, but, at a forecast 6.2% in 2017, would still be far higher than global averages. Crucially, the risk of a Chinese ‘hard landing’ has eased.”

So it’s back to the future with the so-called BRICs leading the way out of the depression. We’ll see.

Talking of back to the future, one of the biggest policy calls from mainstream economists has been for governments to launch more infrastructure spending (building roads, rail, bridges, power stations, telecoms etc) to get economies going. So far, this has been largely ignored by governments trying to cut budget deficits with reductions in government investment spending or facing high public debt levels.

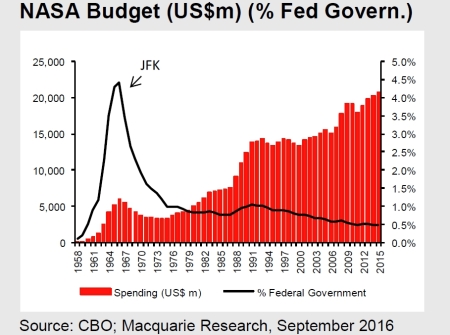

The latest call on this front has come from the economists of the Australian investment outfit, Macquarie. Why not colonise Mars? “It is not as crazy as it sounds,” wrote Viktor Shvets and Chetan Seth from the Macquarie global equities team. “A giant Mars colonisation program would create a vast, capital-intensive industry which would span the globe, create jobs, and address the global economy’s productivity problem.”

You see, the world economy is not growing at a sufficient rate because there are “declining returns on investment”. So what we need to do is to start a huge government programme to colonise Mars, similar to the space program of the 1960s under Kennedy that led to landing on the Moon.

Interestingly, the Macquarie economists are not interested in a global investment programme to help the poorest in the world to develop; to help solve the global environmental disaster or to boost education, health and basic infrastructure in the poorest countries on Earth. No, that is not as useful (profitable) as investing in another planet to get returns on investment up.

The Macquarie solution is the ultimate in Keynesian economic policy (short of ‘war Keynesianism’). It is the idea that there is plenty of capital available but just no ‘investment opportunities’ due to lack of demand. So war or space can offer a way out.

The Macquarie economists think that the huge injection of money and credit into financial assets, that has driven interest rates to zero or below is what has created low returns. But low returns on capital, generated by too much capital, is a neoclassical marginalist theory (that Keynes held to). It is confusing ‘fictitious’ capital with productive capital.

The Marxist view is different. Productive investment is not taking place because of ‘too much capital and low demand’ but because of too little surplus value or profitability from productive capital. And low profitability will not be improved by government spending on a space program. On the contrary. In the 1960s, the space program was affordable because of high (not low) profitability in the capitalist sector. So unproductive expenditure, which no doubt did develop new technology and employment for many, was affordable. That is the opposite now. There is no way out through Mars.

No comments:

Post a Comment