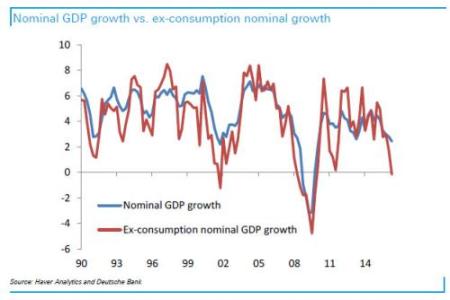

As I reported in a recent post, global economic growth has been slowing from its already below-average level. US economic growth has dropped away in the first half of 2016, along with weak growth in Japan and Europe, slowing growth in China, impending recession in post-Brexit vote Britain and continued recessions in Brazil and Russia, with South Africa and Turkey about to join them. Indeed, the US is growing at its weakest rate since 2010. Worse, everything unrelated to consumer spending is suffering an outright contraction for the first time since the recession ended in 2009, according to Deutsche Bank.

US business investment is dying. Expenditures on new equipment fell 3.5% in the second quarter and is down nearly 2% over the last year. Spending on structures was down 7.9% in the quarter and 7% over the past year. Labour productivity is stalling. Even home purchases are falling, with residential investment down 6.1% in Q2 2016.

As I have pointed out on numerous occasions, US business investment is responding to a fall in corporate profits, down for five consecutive quarters. The latest estimates from FactSet suggest that earnings for the top 500 US companies will decline on a year-over-year basis in the third quarter as well, which would mark the six straight quarter of declining profits. With sales falling, executives are doing what they can to protect margins by slashing spending and cutting inventories.

According to the economists of investment bank JP Morgan, global growth was just 2.2% annualised in Q2 2016, well below the forecasts for this year made by the IMF. The IMF expects 3.1% growth this year and 3.4% growth next year. JPM and the World Bank are closer in their estimates, with the latter now expecting just 2.4% global real GDP growth this year. Most economists reckon that when global growth is at 2.5%, the world economy is at ‘stall speed’, meaning that it would drop into recession from that level because investment and consumption growth would collapse.

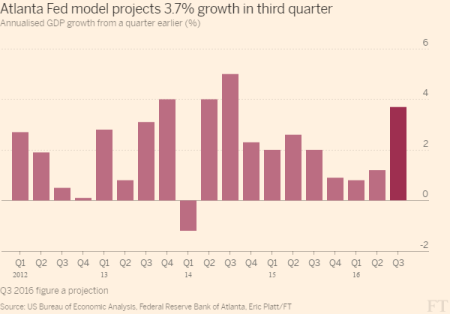

But all is not lost, it seems. In the month of July, there seems to have been some slightly better data. Business activity surveys called purchasing managers indexes (PMIs) for July rose. JPM estimates that the global PMI rose to 51.4 in July from a low of 51.2 in May. That is supposed to mean that global growth has stopped slowing because actual real GDP growth closely follows the global PMI. And the closely followed Atlanta Fed growth forecasting model currently reckons US economic growth will rebound in the current quarter ending at end-September.

Former chief economist for Goldman Sachs, Gavyn Davies now runs an economic forecasting firm, called Fulcrum. Fulcrum also claims that things are looking up with global activity expanding at an annualised rate of 4.1 per cent, a marked improvement compared to the low point of 2.2 per cent recorded in March. So far from ‘stall speed’, the world economy could be “achieving escape velocity, in which the recovery becomes self-propelled, without needing repeated doses of monetary and fiscal policy support to prevent a renewed slowdown”.

Davies admits that “the global economy has been growing at below its trend rate of 3.8 per cent per annum on an almost continuous basis since 2012, with only a few brief periods of slightly better performance”, but things could be about to change.

And JP Morgan, having shown that global economic growth has slowed in Q2, also reckons things are about to improve. Their economists commented that “The long-awaited rebound in global manufacturing appears to be in the offing. Global consumer goods demand accelerated sharply last quarter while the latest data suggest that a contraction in capital spending is about to end.” JPM reckons the great investment downturn could be ending, “after slipping in the four quarters through 1Q16, business capex will just stabilize in the year through 4Q16 before strengthening by 3%-4% in 2017.”

Why should this happen? Well, JP Morgan economists reckon that business investment and profits are closely correlated – “both business confidence and profit growth are highly statistically significant in explaining capital spending.” JP Morgan reckons that business spending “is less a function of borrowing costs than of an assessment of the outlook and profitability. On balance, this model explains 70-85% of the variation in business equipment spending growth”.

So once again, mainstream economics confirms what Marxist economics has always argued: business investment is driven by profitability. For example, mainstream economists Kothari, Lewellen and Warner from three American business schools, recently published a paper called The behavior of corporate investment and found a close causal correlation between the movement in US business investment and business profitability. Like JP Morgan, they found that “at least three-quarters of the investment decline can be thought of as a historically typical drop given the behaviour of profits and GDP at the end of 2008. Problems in the credit markets may have played a role, but the impact on corporate investment is arguably small.”

JP Morgan admits that business investment and profits growth are “currently quite depressed” but if GDP growth picks up and commodity prices do also, then there could be a “turn-up in the profits cycle”. And that would lead to an investment recovery, and with it, faster economic growth. But wait a minute. Economic growth is going to speed up because investment is going to speed up, because profits are going to rise, because economic growth is going to speed up. There appears to be a circular argument here.

While JP Morgan’s economists have recognised the high correlation between business investment and profits, they have failed to identify the causal direction. As I have argued before, the Keynesian-Kalecki view is from spending (consumer and investment) to profits and wages, while Marxist view is that it is from profits (and exploitation) to investment and then income, employment and spending. Getting that direction right is essential to understanding the trajectory of the capitalist economy. Corporate profits are falling in the US, Japan and Europe – and so follows business investment. Unless that changes, the major economies are more likely to contract, not speed up. Optimism could be dashed again.

No comments:

Post a Comment