This time last year I did a post on why productivity growth in all the major economies has slowed down.

As I explained in that post, the productivity of labour, as measured by output per worker or output per hour of worker, is a very good measure of the productive potential of capitalism. Economies can increase their national outputs by employing more people to work (from a rising population of working age) or they can do so by increasing the productivity of each worker. With population growth slowing in most major economies and globally, productivity growth is the main method of raising global output and – given the huge caveats of inequality or income and wealth and the lack of production for the majority’s needs) – the living standards of the world’s population.

Capitalism is a mode of production that aimed specifically at raising the productivity of labour to new heights, compared to previous modes of production like slavery, feudalism or absolutism. That’s because capitalists, in competing to obtain and control more profit (or surplus value) from the labour power of workers, were driven to mechanise and introduce labour-saving technologies. So if capitalism is no longer delivering increasing productivity through investment in technology then its raison d’etre for human social organisation comes under serious question. Capitalism would be past its ‘use-by date’.

And as last year’s post said, global productivity growth has fallen back, particularly since the Great Recession began in 2008 and shows no signs yet of recovering to previous levels. This is vexing and worrying the ruling economic strategists, particularly as mainstream economics has no clear explanation of why this is happening.

Global labour productivity remains below its pre-crisis average of 2.6% (1999-2006)

Only this week, the vice-chair of the US Federal Reserve, Stanley Fischer, looked at the state of US economy. He started by claiming the success of Fed monetary policies in achieving virtually full employment again in the US: “I believe it is a remarkable, and perhaps underappreciated, achievement that the economy has returned to near-full employment in a relatively short time after the Great Recession, given the historical experience following a financial crisis.”

However, Fischer noted that growth in output had not been so impressive. And this is clearly due to the slowdown in productivity growth. “Most recently, business-sector productivity is reported to have declined for the past three quarters, its worst performance since 1979. Granted, productivity growth is often quite volatile from quarter to quarter, both because of difficulties in measuring output and hours and because other transitory factors may affect productivity. But looking at the past decade, productivity growth has been lackluster by post-World War II standards. Output per hour increased only 1-1/4 percent per year on average from 2006 to 2015, compared with its long-run average of 2-1/2 percent from 1949 to 2005. A 1-1/4 percentage point slowdown in productivity growth is a massive change, one that, if it were to persist, would have wide-ranging consequences for employment, wage growth, and economic policy more broadly. For example, the frustratingly slow pace of real wage gains seen during the recent expansion likely partly reflects the slow growth in productivity.”

Why is this? Fischer presents various explanations: the mismeasurement of GDP growth; low business investment; a slowdown in new technology that could boost productivity; and/or the failure any new technology to spread to wider sections of the economy.

The first explanation has a lot of support. The argument is that the traditional measure of output, the Gross Domestic Product, is a very poor measure of ‘welfare’ or the production of people’s needs. This argument has been most well presented in a book by Diane Coyle. (http://www.enlightenmenteconomics.com.) called GDP: A Brief But Affectionate History . Coyle argues that GDP is an ‘abstract’ idea (as it clearly is) that leaves out important services and benefits and puts in unnecessary additions. Here is one example offered by John Mauldin: “If I purchase a solar energy system for my home, that purchased immediately adds its cost to GDP. But if I then remove myself from the power grid I am no longer sending the electric company $1000 a month and that reduces GDP by that amount. Yet I am consuming the exact same amount of electricity! My lifestyle hasn’t changed and yet my disposable income has risen.”

Yes, but what Coyle’s critique fails to recognise is that GDP is not designed to measure ‘benefits’ to people but productive gains for the capitalist mode of production. Electricity on the grid is part of the market, electricity made at home is not; cleaning houses and office for money is part of the market and is included in GDP; cleaning your home yourself is not marketable and so is not in GDP. That makes perfect sense from the point of capitalism, if not from people’s welfare. As Mauldin says “GDP is a financial construct at its heart, a political and philosophical abstraction. It is a necessary part of the management of the country, because, as with any enterprise, if you can’t measure it you can’t determine if what you are doing is productive”.

Many have argued recently that many new technological developments are not measured in the GDP figures: “because the official statistics have failed to capture new and better products or properly account for changes in prices over time” (Fischer). But as Fischer comments, “most recent research suggests that mismeasurement of output cannot account for much of the productivity slowdown.”

That brings me to the main argument offered by mainstream economist, Robert J Gordon, in his magnum opus, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living Since the Civil War. I have discussed Gordon’s thesis before in this blog ever since he first presented it back in 2012. Gordon reckons that the evidence shows productivity growth is currently low because that it where it is usually. There have been periods of fast-growing productivity when technical advances spread widely across economies, as in the early 1930s and in the immediate post-war period.

Productivity growth rose from the late nineteenth century and peaked in the 1950s, but has slowed to a crawl since 1970. In designating 1870–1970 as the ‘special century’, Gordon emphasizes that the period since 1970 has been less special. He argues that the pace of innovation has slowed since 1970 and furthermore that the gains from technological improvement have been shared less broadly.

In Marxist terms, this suggests that capitalism is now exhibiting exhaustion as a mode of production that can expand to lower labour time and meet people’s needs. The current technical innovations of the internet, computers smart phones and algorithms etc are nowhere near as pervasive in their impact as electricity, autos, medical advances and public health etc were in previous periods. So globally, capitalism cannot be expected to raise productivity growth from here. Indeed, there are many ‘headwinds’ likely to keep it lower, says Gordon.

So why has productivity growth slowed and will it continue? Mainstream economics offers all sorts of explanations. The first, as we have seen, is to argue that productivity growth has not really slowed because it is not being measured properly in the modern age of services and the internet.

The second is to argue that the slowdown is temporary and caused by the global financial crash and the subsequent Great Recession. The legacy of crash is still very high levels of debt, both private and public, and this is weighing down on the capacity and willingness of the capitalist sector to invest and expand new technologies. Noah Smith, the Keynesian blogger struggled with debt as the main cause of recessions and slowdowns. Robert Shiller, the Nobel prize winning ‘behavioural’ economist, on the other hand, reckons that the slowdown is due to “hesitation.” “Economic slowdowns can often be characterised as periods of hesitation. Consumers hesitate to buy a new house or car, thinking that the old house or car will do just fine for a while longer. Managers hesitate to expand their workforce, buy a new office building, or build a new factory, waiting for news that will make them stop worrying about committing to new ideas.”

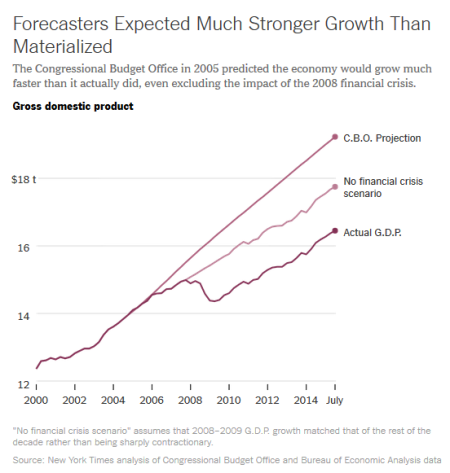

There is no doubt that the global financial crash has driven growth rates in the major economies down – indeed that is part of the definition of what I call The Long Depression that capitalism is now suffering (and all of us, of course, as a result).

And one key factor in that slowdown has certainly been the huge rise in debt, particularly corporate debt, since the end of the Great Recession. As a recent analysis by JP Morgan economists pointed out: “Corporate business, in particular, has borrowed aggressively in recent years, often using the proceeds to buy back shares. Ratios of corporate debt to GDP or income are starting to look rather high'” Indeed US corporate debt is now at a post-war high.

And there is no doubt that capitalist companies are ‘hesitating’ about investing in new technology in a big way. But why? Shiller reckons that “loss of economic confidence is one possible cause.” But that is merely stating the question again. Why has there been a loss of economic confidence? Shiller’s response is to suggest that nobody is willing to invest because of fears about “growing nationalism; immigration and terrorism” So it’s all due to political and cultural fears – hardly a convincing economic thesis.

Yes, high debt and low ‘confidence’ are factors that will lead to low and even falling investment in technology and therefore in generating low productivity growth. But they are only factors triggered, Marxist economics would argue, because the profitability of capital remains low, particularly in the productive sectors. Yes, profit rates in most economies rose from the early 1980s up to the end of the 20th century while investment growth and real GDP growth slowed. But most of that profitability gain was in unproductive sectors like real estate and finance. Manufacturing and industrial profitability stayed low, as several Marxist analyses have shown.

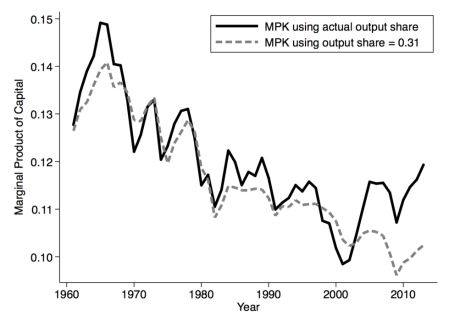

Even mainstream economics, using marginal productivity categories, reveal something similar. Using marginalist mainstream categories, Dietz Vollrath found that the ‘marginal productivity of capital’ fell consistently from the late 1960s. Capitalism has become less productive ‘at the margin’. Marxist economics can explain this as due to a rising organic composition of capital (more technology replacing labour) leading to a fall in the rate of profit (return on capital). Post the Great Recession, the marginal productivity of capital rose because the share going to profit rose. In Marxist terms, the rate of surplus value rose to compensate for the rise in the organic composition of capital. Here’s Vollrath’s chart showing the time path in capital productivity from 1960 to 2013. If you remove the effect of rising profit share, the falling productivity of capital continued (dotted line).

So the conclusion of last year’s post still holds; “Productivity growth still depends on capital investment being large enough. And that depends on the profitability of investment. There is still relatively low profitability and a continued overhang of debt, particularly corporate debt, in not just the major economies, but also in the emerging capitalist economies. Under capitalism, until profitability is restored sufficiently and debt reduced (and both work together), the productivity benefits of the new ‘disruptive technologies’ (as the jargon goes) of robots, AI, ‘big data’ 3D printing etc will not deliver a sustained revival in productivity growth and thus real GDP.”

No comments:

Post a Comment