The finance ministers of the top 20 economies of the world met in Chengdu, China this weekend and they were worried. Global economic growth continues to slow and monetary policy (central bank easing through cutting interest rates and engaging in ‘quantitative easing’) does not seem to be working in restoring levels of economic growth achieved before the Great Recession.

And the decision of the British people to vote to leave the European Union is an extra shock to world capital economy. Brexit implies further slowdown in world trade expansion; one way that the G20 financial authorities hoped could get global growth going again. The prospect (still unlikely) that Donald Trump could win the US presidential election in November also raises the risk that the largest and most important economy in the world could move towards protectionism on trade and finance, as well as imposing and supporting tighter restrictions on the free movement of labour. The great days of globalisation could be over.

Prior to the meeting, the IMF had to announce yet another reduction in its forecast of global growth. The reduction was not much, but it was the fifth time in 15 months. The IMF now expects global GDP to grow at 3.1 percent in 2016 and at 3.4 percent in 2017 — down 0.1 percentage point for each year from estimates issued in April. And this forecast is still well above the much more pessimistic June forecast of the World Bank, which is expecting only 2.4% growth in 2016 from the 2.9 percent pace projected in January.

The G20 leaders said they were opposed to trade protectionism “in all its forms” and were committed to further monetary and fiscal measures to “strengthen growth”, but there was again no commitment to common action. US Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew said ahead of the meeting that it was “not the right time for coordinated action similar to that in 2008-09 following the global crisis because economies face different conditions.” So basically, they are doing nothing and relying on already failing policy methods.

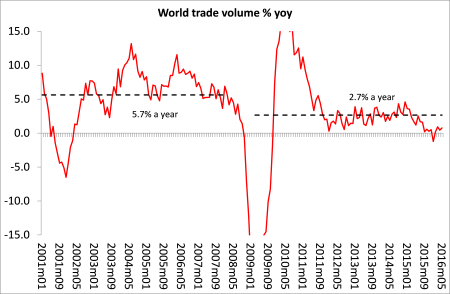

But the strategists of global capital are worried. First, nothing appears to be working and real GDP and trade growth are slowing. Look at the latest data on world trade growth by the Dutch research group CPB. World trade contracted yet again in May and is now up only 0.75% from May 2015 in volume (that’s excluding price effects). Growth in 2016 is well below the post-Great Recession average of 2.7% a year, which in turn is less than half the rate of world trade growth before the global financial crash (at 5.7%).

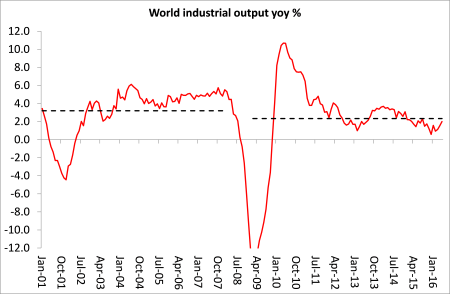

And it is not just trade. World industrial production, the best measure of growth in the productive sectors of the world economy, is hardly moving and is actually falling in advanced capitalist economies, according to CPD. Again industrial production growth is below even the post-crash average, which in turn is below the pre-crash average.

But it is not just the economic performance of the global economy that worries the G20 leaders; it is the political effect that this is having on the people of the major economies. They are losing confidence in mainstream politicians because they cannot deliver on better living standards and any recovery for the majority since the Great Recession. The leaders talk big about recovery and improving conditions but the majority don’t see it. This partly explains the Brexit vote in Britain and the rise of so-called populist parties in Europe and Trump in the US.

Three recent reports by mainstream economic experts show that the perception of the majority that they have not seen any ‘recovery’ is based on reality. McKinsey, the international management consultants, published a report called Poorer than their parents? A new perspective on income inequality, which showed that the real incomes of about two-thirds of households in 25 advanced economies were flat or fell between 2005 and 2014!

McKinsey concludes that “Most people growing up in advanced economies since World War II have been able to assume they will be better off than their parents. For much of the time, that assumption has proved correct: except for a brief hiatus in the 1970s, buoyant global economic and employment growth over the past 70 years saw all households experience rising incomes, both before and after taxes and transfers. As recently as between 1993 and 2005, all but 2 percent of households in 25 advanced economies saw real incomes rise.

Yet this overwhelmingly positive income trend has ended. “between 2005 and 2014, real incomes in those same advanced economies were flat or fell for 65 to 70 percent of households, or more than 540 million people (exhibit). And while government transfers and lower tax rates mitigated some of the impact, up to a quarter of all households still saw disposable income stall or fall in that decade.”

McKinsey forecasts that: “If the low economic growth of the past decade continues, the proportion of households in income segments with flat or falling incomes could rise as high as 70 to 80 percent over the next decade. Even if economic growth accelerates, the issue will not go away: the proportion of households affected would decrease, to between about 10 and 20 percent—but that share could double if the growth is accompanied by a rapid uptake of workplace automation.” Who says this is not A Long Depression!

Last week, Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, published a speech of his that he made in Port Talbot, Wales, in June. Port Talbot is the home of the British steel industry, now owned by the Indian steel giant, Tata. Tata has announced that it wants to sell the business there or close it down, putting thousands of steel workers out of work.

Now Haldane has been a bit of a maverick in central bank circles in the past. I have already pointed out in previous posts that he considers that the finance sector in capitalism adds ‘no value’ whatsoever and can be even negative for the global economy – that is very ‘off message’ for a bank official!

At Port Talbot, he made a speech called “Whose recovery?”. In it, says that, when he visited a community centre in Nottingham in the middle of England: “I was stopped in my tracks by a forest of furrowed brows and a phalanx of probing questions, not all of them gentle. “What exactly do you mean by recovery?” one asked. “My charity is dealing with 50% more homeless people than three years ago.” Every other charity in the room had similar stories to tell. Whether it was food banks, mental health problems or drug addiction, all of the numbers were up. The language of “recovery” simply did not fit their facts.”

In the UK’s very weak economic recovery since 2009, it is the rich, those in the south and those who are older than have ‘recovered’. The rest have not at all. Haldane commented. “At least as measured by GDP, the economy and society as a whole is 5% better off. But is it? The income of the already-rich has risen by just over 10%, while the income of the already-poor as fallen by 50%. Does the former really swamp the latter when it comes to the well-being of society?”

Haldane found that in only two regions – London and the South-East – is GDP per head in 2015 estimated to be above its pre-crisis peak. In other UK regions, GDP per head still lies below its pre-crisis peak, in some cases strikingly so. For example, in Northern Ireland GDP per head remains 11% below its peak, in Yorkshire and Humberside 6% below and here in Wales 2% below.

Since the end of the Great Recession, the largest gains in income have come in regions where income was already high – London (incomes more than 30% above the UK average) and the South-East (14% higher). Contrarily, some of the larger losses have been in regions where income was already-low – Northern Ireland (18% lower than the UK average) and Yorkshire and Humberside (14% lower). Haldane concluded that “it is clear that recovery has been associated with both the incomes and, more strikingly, the wealth of the least well-off having broadly flat-lined. Recovery has not lifted all boats, especially some of the smaller ones. This pattern may go some further way towards solving the recovery puzzle. Whose recovery? To a significant extent, those already asset-rich.” And this is the UK, which has supposedly recovered better than the rest of Europe.

Then there is the report by Macquarie, the Australian based investment firm (WhatCaughtMyEye200716e248606). Macquarie reckons that the structure of the labour force is shifting towards the modern equivalent of ‘lumpenproletariat’ (they use the Marxist term). Most people are increasingly employed in more precarious and low-paid occupations. This applied to “as much as 40%-45% of the labour force”. The same trend is evident in most other developed economies. Macquarie have not have got the concept of lumpenproletariat right. What the investment firm describes is really the normal position of the labour force under capitalism: continual tendency to join the ‘reserve army’ of labour.

This is why the ‘recovery’ has not been felt by the majority as they are locked into insecure jobs with low incomes. Inequality of income and wealth continues to worsen, while the productivity of the labour force languishes across the board. US labour productivity has stagnated from the 1980s onwards. “Over subsequent decades, stagnant productivity was pretty much replicated across most economies. Declining productivity growth reflects that an increasing proportion of the labour force and employment is essentially “warehoused” in lower productivity occupations, pending either their final elimination and replacement”, says Macquarie.

The last six years represented essentially a continuation of a trend towards lower-end jobs in the US, which started in the mid-to-late 1980s. “On our estimates, low end/contingent jobs represented ~36% of the total labour force in 1990 and today it is ~42% (or around 52m jobs vs. 33m in similar occupations in 1990) whilst the high end jobs used to be 45%-46% and today the number is closer to 43.5%.”

So the world economy has still not recovered to pre-crisis levels. More important, the majority of households in the major economies have seen no ‘recovery’ at all. The great jobs expansion is been mainly in low-paid, low productivity sectors or in self-employment where incomes are relatively lower.

The solution to this depression of incomes, output and productivity from mainstream economics varies from the Keynesians, who yet again advocate more government spending as monetary policy is exhausted (see this latest piece by Summers and Eggertsson) to the Austrian monetarists who reckon the problem is excessive monetary easing by central banks that has created a credit bubble without any impact on the real economy. The Keynesians want more government spending and the Austrians want less credit expansion. As I and my co-author G Carchedi showed in a The long roots of the present crisis, neither policy solution will work.

What worries the strategists of capital is that their failure to get capitalism going again or reduce the burden for the majority to pay for it is beginning to end their political control of the majority. Brexit, the rise of Trump and other ‘populist’ leaders now threaten the end of the neoliberal ‘free trade, cheap labour’ agenda of globalisation.

No comments:

Post a Comment