I have to say that I did not expect the referendum on whether Britain should leave the European Union or not would have a big effect on global markets. And over the long term, I do not expect it to have a great impact on the relative health or otherwise of British capitalism. Much bigger damage could be expected from the next global recession, which is coming up like a storm on the horizon at increasing pace. See my post on Brexit.

But it seems that the growing possibility (not probability) that Brexit could be a reality is really exercising the decisions of international investors (banks, hedge funds, etc) in financial assets. World stock markets, after a significant rally towards previous highs in the last three months, have now started to turn down.

Three things are driving this reversal.

First, the fear of ‘Brexit’; that it will lead not only to a severe downturn in the UK economy as the tortuous negotiations for withdrawal begin (up to 2019 according to the ‘leave’ camp!), but also trigger a new recession in the rest of Europe.

Second, the renewed worry that China, the world’s second biggest economy, is showing further signs of economic slowdown, with the risk of a credit bust.

And third, that the US economy, the relatively best performer among the major economies since the end of the Great Recession, is also showing weaker economic activity just at a time when the US Federal Reserve reckons it needs to hike interest rates to ‘cap’ inflation (and wage rises). ‘Uncertainty’ is the word of the moment – and, as mainstream economists continually tell us, ‘confidence’ about the future is paramount for investment.

There appears to be growing uncertainty about the result of the UK referendum with just over a week to go. Brexit polls now indicate a steady downtrend in the lead for ‘remain’ that has brought the outcome of next Thursday’s vote near to a toss-up. The downtrend appears driven by the undecided group breaking in favour of ‘leave’. This is the opposite of what often happens in advance of such groundbreaking votes, when a bias for maintaining the status quo tends to emerge. I still think that it is likely that there will be a majority for ‘remain’, but as the Duke of Wellington said at the end of the Battle of Waterloo against Napoleon, it could be “damn close run thing”.

What is worrying financial markets is that a vote for Brexit would have a damaging impact on the UK economy. And that is surely right – at least in the short term. There have been many estimates of the gain or loss from Brexit for the UK economy – see my Brexit post. But the latest from the UK treasury reckons UK GDP would be 3.6% lower after two years than if the UK voted to stay, unemployment 520,000 higher and the pound 12% lower. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has added that — instead of an improvement of £8bn a year in the fiscal position if the net contribution to the EU fell — the budget deficit might be £20-40bn higher in 2019-20 than otherwise. These fears have already hit sterling, which has fallen 5-6% against other major currencies since the referendum campaign got under way.

But the main reason that the UK economy would suffer is because it is weak anyway. British capitalism has increasingly turned itself into a ‘rentier’ economy, where it get its surplus value, not mainly from the production of things and services to sell at home and abroad, but increasingly from acting as a banker and investor and business advisor for other capitals overseas, and raking off a percentage in interest, rents and fees. That means the British population must import more and more goods from elsewhere to be paid for by monies ‘earned’ from financial and business services; and most important, from the willingness of foreign capitalists to put their money into banks and financial institutions in the City of London.

So the UK runs a massive current account deficit on goods and services with the rest of the world (currently 7% of GDP).

And it finances this deficit through what Bank of England governor Mark Carney called “the kindness of strangers”. By this he meant the inflow of foreign direct investment, foreigners purchase of UK government bonds and corporate stocks, and what has been called ‘hot money’, the movement of short-term cash and deposits into British banks.

Now these ‘capital flows’ are beginning to swing from the positive to the negative too. The graph below shows the UK’s ‘capital account.

The yellow block is direct investment in British companies or setting up foreign ones on British soil. That is pretty steady – but who knows if it would continue after Brexit. Portfolio investment (blue block) shows that foreigners still want to buy and hold UK government bonds and stocks (as a ‘safe haven’). But the light blue block is the ‘hot money’ – and it is flowing out big time up to 2015. This has accelerated in 2016. If that outflow continues, then there will huge downward pressure on the pound, which may help exports down the road, but in the short term will drive up import prices and inflation, cutting into real incomes for the average household and raising costs for British industry.

Talking of capital outflows – that has been the issue in China as well. As economic growth has slowed from double-digits to under 7% a year now (possibly lower) ,the Chinese currency has weakened and Chinese billionaires have been trying shift their money into dollars and out of the control of the Chinese authorities. Dollar reserves have plummeted.

In a previous post, I argued that China’s slowdown will not bring the world down. But renewed worries about the failure of the Chinese government to turn things round and growing talk by the likes of the IMF in a recent report of the dangerous levels of debt, particularly corporate debt, owed to the Chinese banks has recently revived concerns that China could implode.

The most significant sign that all is not well is the recent drop in investment growth in China. For the first five months of this year, investment rose ‘only’ 7.5%. That may sound a lot compared to the pathetic rate achieved by the top capitalist economies (where investment is even falling), but compared to history, the current Chinese rate is way too low to sustain economic growth at even current levels. Even more worrying, investment by private firms slowed to a record low, with growth cooling to 3.9% from double-digits last year. Private investment accounts for about 60% of overall investment in China. And this investment and debt is having less and less an effect on sustaining growth and productivity.

The government has tried to boost infrastructure spending to compensate but not allow credit growth to get out of hand and cause a financial bust. It is a dilemma that has provoked disagreement at the top of the Chinese Communist leadership, between the president Xi and the prime minister Li (in charge of economic policy). The former wants ‘structural reform’ ie cuts in ‘zombie state’ companies, while the latter wants to engage in more credit injections. And the battle between those who want to move further down the capitalist road towards privatisation and a market economy (backed by the World Bank and the IMF) and those who want to preserve ‘Chinese socialism’ with a state owned, party controlled planning mechanism smoulders on.

But the third point in the current nexus of worry is the US economy. As Larry Summers, former US Treasury secretary, promoter of the thesis of ‘secular stagnation’, and regular columnist in the UK’s Ft, pointed out, “Any consideration of macro policy has to begin with the fact that the economy is now seven years into recovery and the next recession is at least on the far horizon. While recession certainly does not appear imminent, the annual probability of recession for an economy that is not in the early stage of recovery is at least 20 per cent. The fact that underlying growth is now only 2 per cent, that the rest of the world has serious problems, and that the US has an unusual degree of political uncertainty, all tilt toward greater pessimism. With at least some perceived possibility that a demagogue will be elected as President or that policy will lurch left, I would guess that from here the annual probability of recession is 25-30 per cent.”

Last month’s US jobs report was particularly weak and the US Federal Reserve’s own measure of employment conditions is falling at a rate that often presages an economic slump.

The Fed is still dithering over whether to raise its policy interest rate or not this year. It is still desperately hoping that the US economy is going to pick up in the second half of the year. But at best, real GDP growth will be no more than 2%, as it has been more or less for the last five years. At worst, it could slow or even contract.

And don’t forget my usual hobby-horse indicator of the health of a capitalist economy: the profitability of the capitalist sector and business investment. The latest data show falling corporate profits. And that usually presages a fall in business investment and from there to a recession – see the close correlation in the graph below.

So if the Fed does go through with a hike in rates, that could add another negative to the conjunction of events (Brexit, China) tipping the world into a new recession.

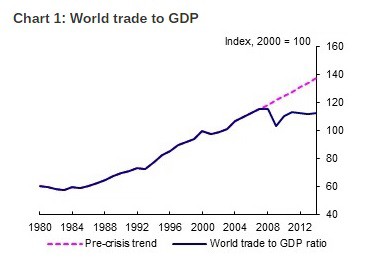

As I have reiterated on many occasions, the world economy is in a Long Depression of below trend economic growth, near deflationary conditions, stagnant business investment and very weak productivity growth. Most significant, world trade growth has slumped well below trend.

And at the same time, the great ‘globalisation’ of capital expansion around the world has reversed. Capital flows between the major economies had reached 45% of their GDP in 2007. Now that has fallen to just 5%.

And the latest estimate by JP Morgan of global manufacturing output growth, the key sector of productive expansion, shows a level near zero.

The vote on Brexit has assumed a greater global significance than I originally thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment